Rob Whitehurst

From Discourse 4

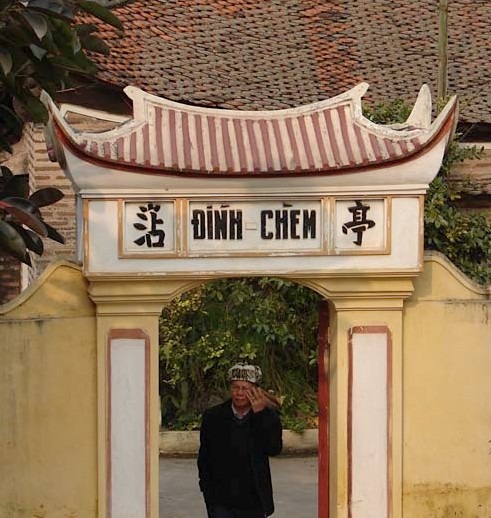

Rob Whitehurst. The ends of the Vietnamese kite pictured are tensioned to flare up in a way reminiscent of the eaves of traditional Vietnamese buildings, particularly temples and communal houses.

In early December this past year I had the opportunity to visit Mr. Nguyen Huu Kiem, the 4th generation kite builder and guiding light of the kite building community of Ba Duong Noi, a village about 15 miles up the Red River from the center of Ha Noi, Viet Nam. Vietnamese friends from Ha Noi had made his acquaintance last year when he made and sent me a traditional bamboo kite whistle with three tubes. How exactly I came to get a kite whistle from him is a story I need to tell here.

Years ago I had seen an old article by an early 20th century French traveler who was going up to Ha Noi from Hai Phong in the early spring. He wrote about the scores of kites which flew over the countryside, all of a particular design and all with whistles mounted on them, which keened and moaned day and night for the days and weeks they stayed in the air in the constant spring monsoon. An engraving, which I saw years later, showed a singular design of kite which is unique to the Red River Delta around Ha Noi and which I never found anywhere else. That image stayed tucked away in my mind for several decades and when in 2005 I traveled to Ha Noi myself I was disappointed to not see any kites. I mentioned this to several friends and when I returned in the spring of 2006 one of them had gotten me a whistle made, and after asking around I was able to see several of the old kites on walls and hanging on display. I ended up commissioning several more of the whistles to take home. Back in New Orleans without a kite to mount the whistle on I would occasionally hold one out of my truck window when driving down quiet avenues in the late evenings. The image of an older adult with a kite whistle out of his truck window is very hilarious to many Vietnamese, and when it was mentioned in a newspaper article I ended up getting the really beautiful traditional whistle that Mr. Kiem made for me.

So this December when back in Ha Noi, I very much wanted to meet him, and it was so arranged. Friends drove me up the dike- top road, which runs along the Red River for miles. Along the massive ancient dike, the suburbs of the growing city of Ha Noi are slowly engulfing the riverside villages as they spread northwest. When we turned off of the dike onto the road leading down into the village, we finally parked at a small bend and were met by Kiem, who led us to the site where all the village kite builders are constructing anew the temple to the sky spirit which is the patron “genie” of the village.

Across the road lay the empty field where the spring kite festival is held. The collection of original characters who daily gather to contribute labor and cheer to the building project was made up that day of older villagers, as the younger members of the community were in school. Their intention is to have the building complete by the spring of 2010 and then to play host to the national kite festival, which will be held as part of the celebration of Ha Noi’s one thousand year anniversary. Kiem introduced me and I was met with warm greetings, lots of smiles and laughter as they found that they could understand my spoken Vietnamese in spite of my funny accent. The temple “furniture” was protected by a temporary shelter, and stacks of tiles and bricks lay around the compound. I took photos of everything and everyone, and broke out my laptop to show them my kite folder full of photos from other places. We shared the very bitter tea which is part of every meeting in rural Viet Nam, and I introduced myself to the prominently displayed donation box with a suitable contribution.

December is not the time of year to fly kites traditionally, so I cannot write that I had the pleasure of seeing and photographing any of the things airborne, but I mostly was interested in seeing how the kites and kite whistles were constructed. After the visit to the temple compound, Kiem took us to his home in the village, introducing us to his wife and 94-year-old mother, and we again sat down to very bitter tea, this time in front of his family altar with its photographs and pictures of ancestors, among them several kite builders. After visiting there for a short time, he disappeared upstairs to return with a kite.

The ones I had seen before had been covered with paper, but this first one he brought down was covered with a type of clear plastic. Photographs of this kite make very clear how the two bamboo “cross spars” were fastened to the central “spine,” and then how at their tips the spars are joined to form a long symmetrical leaf shape, much longer on the horizontal than vertical axis. Furthermore a line which goes from each end of the “leaf” to the center of the spine is tensioned to flare the ends up in a way reminiscent of the sheer of a boat, or as I started to see, the curved-up ends of the eaves of traditional Vietnamese buildings, particularly temples and communal houses. The transparency of the plastic, applied to the upper side of the kite frame, also allowed me to see that the line, spars, and spine underneath were then “taped” with strips of the same material to reenforce the kite, and as Kiem explained, to make it fly better by “smoothing” the surface. Kiem went on to bring down two more kites, an old one and a recently built one. He showed me how the whistles are fastened to the kites, with a hole in the spine for the bottom of the “whistle stick” and with a number of short supporting lines to hold it rigid and at the correct angle facing the wind. You can see that these whistles are mounted on top of the kites. Two- and three-tube whistles are common but as many as five-tube whistles are mounted on very large kites. And these kites are large in their width. The smallest I have seen is about 6 feet wide, so that bringing one home on the plane is not an option. Some of the larger ones are close to 12 feet across.

Rob Whitehurst. Handmade bamboo kite whistles are fastened to kites with a hole in the spine for the bottom of the “whistle stick” and with a number of short supporting lines to hold it rigid and at the correct angle facing the wind.

When I mentioned that I would like to spend a few weeks with him in the village learning all of his “secrets” he laughed and told me that there aren’t any secrets, that he gives away all of his knowledge to anyone who wants to learn. He has a class for the village children in the summer when they are out of school and greets anyone who is interested with enthusiasm. When I asked to see his “workshop” he took us upstairs to show us the way he constructs the kite whistles. I had thought from the whistle he sent me that he must have some sort of lathe to make the caps on the whistle ends, and perhaps also a way to “turn down” the bamboo tubes of the whistles, but he doesn’t. With fairly simple tools he cuts down from the outside the thickness of the bamboo tube-walls to a very uniform thinness, then he takes rough discs of green wood – magnolia is what I understood – and marks the perimeter of the tube to carve exactly matching caps that fit over each tube end.

Each tube is actually two whistles, with a “stop disc” let into each end almost to the middle of the tube. The space between the two discs is where the short bamboo spar – or stick on which the whistles are mounted – passes through. The end caps of soft wood are shaped by hand tools on a heavy block to what seems like perfectly curved surfaces in-and-out and pierced with sound openings. With only an afternoon and not the best camera for the task, I could not fully document the process. The best would be to watch youngsters during the summer class learn how to make these whistles and kites. I am sure that there are many tricks to the making of these things which are not immediately obvious.

I confess finally that I am not a kite fanatic or even a routine kite flier. I have sailed extensively and I have certainly flown kites as a youngster and with my own children. The tradition of kites in Viet Nam, particularly in the north, is one which was often a village activity, important to adults perhaps more so than to children. Ba Duong Noi has their yearly kite festival on the 15th day of the 3rd lunar month, this year on the 9th or 10th of April. The village is not so far from Ha Noi that it would be uncomfortable to visit during the day while staying in the city at night. The traditional kite flying which was so wide-spread historically was put aside during the many decades of war, and then was not readily resumed as Vietnamese society met television, the internet, and the enticements of a bright new world.

There may never again be scores of hundreds of these unique kites over the Red River Delta in the spring, but there may be enough individuals who keep up the tradition so that there will remain every year a time when a few of the kites still climb into the wind, moaning and singing over the land below. And if enough documentation is made of these kites so that they can be replicated, then someday newer generations of Vietnamese may rediscover them, or they may even be seen in other skies around the world.