Paul Chapman

From Discourse 4

Paul Chapman. The BBC’s “Inside Out” films testers in Bristol, England as they maneuver a replica of Pocock’s kite buggy system.

Alistair McKee came around to see me just before Christmas. Alistair works for the BBC and had been put onto me as a source of information on George Pocock, who, in the early 1800 s , practiced the art of aeropleustics in and around Bristol. We had a little rummage around my collection of old kite stuff and turned up a copy of the kite patent by Viney and Pocock, as well as the two classic Pocock books of 1827 and 1851, and various other stuff that included authentic instructions on building the kites and kite carriage. The 1851 book is particularly scarce. In it, you will find the account of a race between three buggies from Bristol to Marlborough, one with a crew of six and the others with three in each buggy. (This was reproduced in The Kiteflier for October 2006.)

Alistair’s project was to make a replica of Pocock’s system and then to test it. This seemed a big challenge, particularly with respect to making an historically accurate replica, since the patent only shows a side view of the power kite and the plate in the books shows a plan view but with no details of the sticks. The “how to make it” book tells you how to make the sticks, but still fails to show the kite framework.

Then Alistair threw me a helping hand. We were looking at my stocks of hard laid hemp and fine cotton cambric, when he said that the cambric looked about right.

“How do you know?”

“Well, the one that I saw was a bit like that.”

“WHAT?”

So then he told me about the kite skins.

It took a couple of weeks to get through Christmas before getting the chance to see the Pocock kite skin. When I arrived, it was already carefully laid out on a bed of acid free paper ready for inspection. And in a box alongside, there was another identical example! (The buses in Bristol are a bit like this: as rare as hen’s teeth and then two turn up at the same time. Anyway, back to the kite skin.)

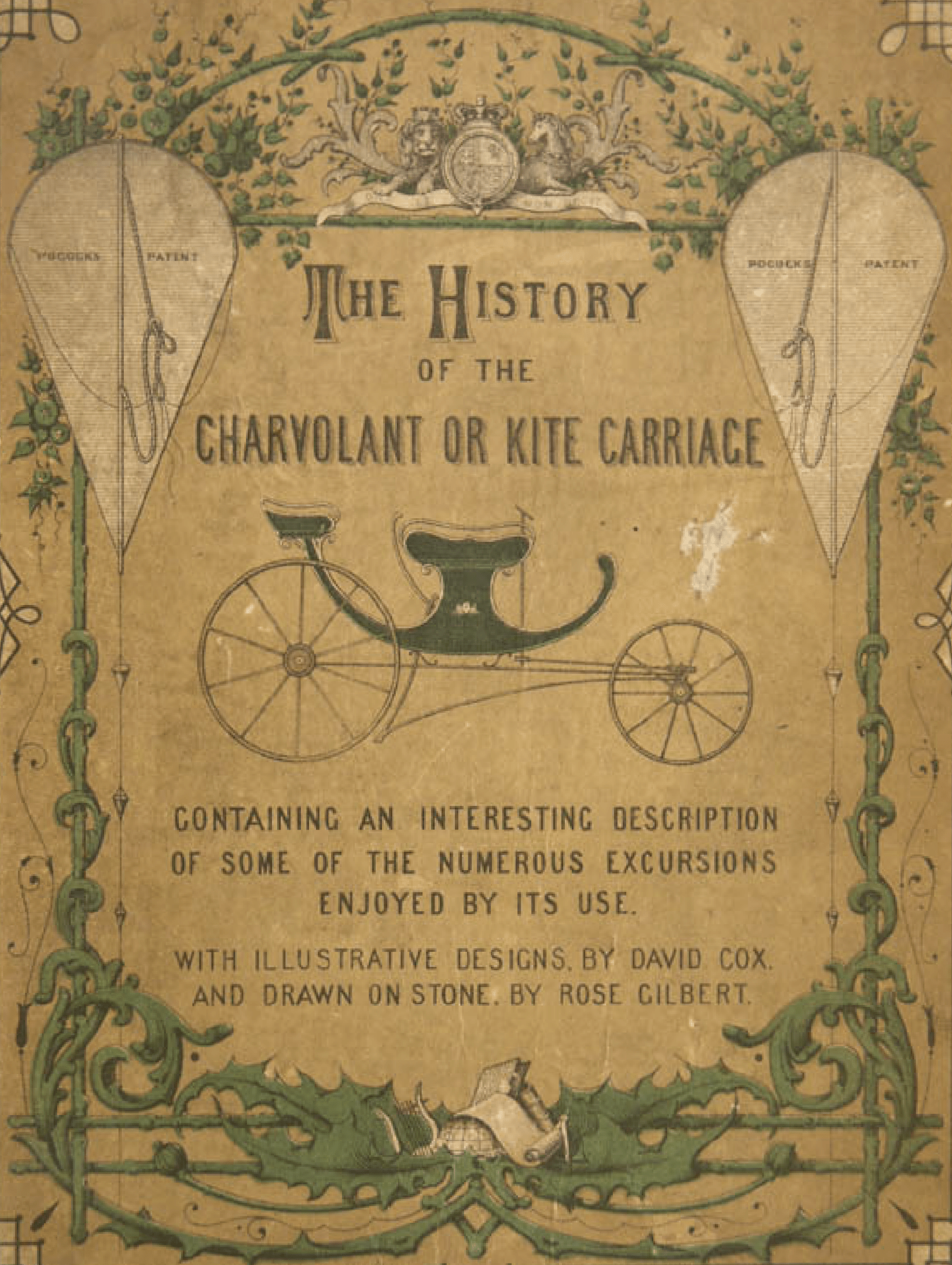

The skins – both of them, as they are identical – have never been made up into kites. From the size of them, they appear to be either pilot kites or the Pocock Patent Portable juvenile kite since the main power kite for the Charvolant was much bigger. The juvenile kites are advertised in the 1851 The History of the Charvolant or Kite Carriage, so my guess is that these are likely to be from about that time. The indigo colored fabric is almost certainly lightweight, closely woven linen. The face has a shiny mercerized type of finish. It is unlikely that the fabric would have been specially made, so I would think that it is some sort of linen umbrella fabric. The skin is made in two halves and sewn together.

The crest image on the kite is different from that shown in the Pocock books; both the lion and unicorn appear somewhat inebriated! It is likely that this would have been a woodblock print.

My sketchbook from the visit shows that the finished kite would be 70” tall and 47” across the wing tips. There are 1.5”-wide hand sewn seams around the slightly bow headed top and 1” seams along the bottom edges. These seams leave gaps at the corners to allow for fittings and fixtures. There are no signs of bridle fittings.

It is my guess that the upright stick, made from straight grained Central American lancewood, connected to a hinge at the top. The hinge formed the center of the “bender” sticks that fit into the top sleeves. The hinge itself would open to about 240 degrees or so. There was also a spreader stick that connected across the bender. There is no gap in the bender sleeve to take a spreader connector, so the only place that this could have connected was from wing-tip to wing- tip (as described in the making instructions, but different from the common belief that the spreader would act like an umbrella spreader). The spreader would control the bender from bowing back too much under wind pressure. I also have a feeling that the sleeves carried a hemp outline string that would connect the sticks to the skin, and then be then tied at the bottom of the kite. This would then allow the kite to be trued up.

The time for flight-testing and filming came on Sunday 11th January. The site was on the buggy beach at the Uphill end of Weston- super-Mare. The wind gods decided to make up for weeks of freezing temperatures and no wind; the anemometer showed a 15- to 25-mph gusting breeze. The men from the BBC were delighted that we had a proper kite wind!

Paul Chapman. 1851’s The History of the Charvolant or Kite Carriage, in which the Pocock Patent Portable juvenile kite was advertised.

Alistair had arranged for the replica to be made by Prop Inventor and Science Presenter Marty Jopson. Marty has a workshop in Leeds and had received copies of all my paperwork so I was intrigued by what would emerge from the BBC’s white van. So was Dom Early because he had been volunteered as aeropleustician for the day.

Marty had made a “proof of principle” system. As he explained it, it would be something like the sort of thing that Pocock could have experimented with had he had the advantage of modern materials. The buggy was a short-coupled affair – a cross between a wheelchair and a go-cart scavenged from old pram parts. The kite itself was of genuine color and a good 10 feet tall, but it was made from a nylon fabric. The straighter and spreader were 8mm glass rods while the bender was a rather insignificant 3mm carbon (or glass) rod. The tail, as specified by Pocock, was a series of vented cone cups. Marty had not had time to make a pilot kite so Dom quickly arranged one.

The wind was really too severe but the team persevered. The pilot was launched but was pretty much overpowered. And then the big kite was ready for testing. Marty had replicated the original control system that comprised a lead line from the head of the kite. Attached to the lead line was a ring that carried another line that ran to the rear of the kite. The kite incidence angle can be adjusted by using the lower line. In Pocock’s system, all the lines were housed in a drag reducing sleeve. Control to either side came from light lines that ran from the wing tips, through the ring, and then down to the aeropleustician. In Pocock’s day, there would be two steersmen, one for pitch and the other for steering. Luckily, Dom is an experienced buggier so he could do the work of two men.

After a little fettling, it was time to squeeze Dom into the Charvolant and let him loose. And, given the strength of the wind, we were amazed by the s ight of the aeropleustician zigzagging in a downwind direction.

Although I was only the observer at this stage, I did manage to get some video. What seemed interesting was the behavior of the pilot kite. This is simply a single line kite whose only function seemed to be to keep the power kite up. What would happen when the power kite was maneuvered, say to the left? The pilot would initially be streaming downwind but then would drift across to add its might to the power kite. I suppose it acted as a damper to the system.

The top speed of Marty’s proof of principle Charvolant was nothing like the 20-25 mph of George Pocock’s kite carriage. Neither did it carry a load of up to 16 cheering schoolboys. But it worked! And afterwards, Dom hitched up a trailer to one of the modern kite buggies and individually sandblasted the entire TV crew.

Broadcast on BBC1 “Inside Out” on Wednesday 21st January at 7.30pm. View footage online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout/content/articles/2009/01/19/west_pocock_kites_s15_w2_video_feature.shtml (click the link “Video: see the Inside Out report”).