Peter Lynn

From Discourse 10

All images by Peter Lynn Kites

First launch and flight of Peter Lynn’s Mega Ray.

First launch and flight of Peter Lynn’s Mega Ray.

INTRODUCTION BY SCOTT SKINNER

After dallying with kites for seven or eight years, I got seriously hooked in 1983 when I walked into Reza Ragheb’s Hi Fli Kites, a store in Aurora, Colorado. Very shortly thereafter, I picked up a Saturday Evening Post and saw the shocking back-page photograph of Steve Edeiken being lifted by a huge kite on the Northwest Coast. Steve’s shocking death sent a wave through the kite world and gave us sobering insight into the power and danger of these behemoths.

I remember one year at the Washington State International Kite Festival when the Dutch “World’s Largest Kite” flew on a light wind day at the beach. I was impressed by the professionalism of the Dutch team in their preparation, communication, and coordination working with volunteers to safely and successfully fly the kite. These two giant kites were so dissimilar, it helps to show the direction of evolution for future giant kites.

The Edmonds Community College kite, for which Steve acted as safety marshal on the day he died, was a then-standard parafoil design with multiple bridles and flares and an open leading edge. It displayed the dangerous characteristics of any large parafoil: rapid inflation, lots of moving lines, and extreme power. The Dutch kite was a very wise step forward in that it had a closed front, so it had to be slowly inflated through the work of a coordinated team. It had only three bridle l ines, and, additionally, guide lines or steering lines on each side. It had been designed to produce less lift than a parafoil design of the day. All of these made it a safer, if less spectacular, flier.

Today, there is a new breed of “World’s Largest Kite,” designed and produced by Peter Lynn in New Zealand. The first three, which were produced so they could be easily transported and flown in three regions of the world, were simple rectangular shapes, inflated through an open leading edge, and supported by a minimum number of bridles as well as supported by steering lines on either side. The kites were also equipped with a trailing line used for rapid deflation and recovery. The simple rectangular shape belied the extreme engineering done by Lynn. Internal lines allowed for complete control of the kite’s airfoil profile, thus enabling Peter complete performance control both on the design computer as well as on the kite field.

Abdul Rahman Al Farsi is the newest owner of the World’s Largest Kite. Mr. Al Farsi, from Kuwait, has become one of the great kite ambassadors of the world: hosting lavish festivals, commissioning numerous kites to show his countrymen their magic, and traveling and interacting with kite promoters and enthusiasts to encourage new kites and new kite promotions. I’m anxious to see this kite fly – it’s a huge manta ray design – as it is another step forward in mega-kite design.

WORLD’S LARGEST KITE BY PETER LYNN

There is a new world’s largest kite (WLK for short), flown in public for the first time at Berck sur mer, France on April 17th. Built by Peter Lynn Kites Ltd. for the Al Farsi Kite Team from Kuwait, it’s a sort of an own-goal in that they (both of them) will be taking the record from themselves – the Al Farsi’s 1019 square meter Kuwait flag kite (also built by Peter Lynn Kites Ltd.) is the existing Guinness record holder.

This new one’s a ray – after the style of the original Mega Ray (now owned and campaigned by German kite personality Lutz Treczok) – but it’s twice as big at 1250 square meters (65 meter wingspan). In the most important respect, rays are an ideal shape for very large kites because almost all their area is “lifting surface,” which is how qualifying area is calculated. Tails and other appendages don’t count.

But they’re also aerodynamically efficient, which makes for some difficulties. Large kites need to be docile fliers and have as little pull as possible. Zooming all over the sky like a high performance traction kite at four times wind speed developing 16 times static pull is not desirable – not least because no available mega-kite mobile anchor (we usually use a 12 ton loader) could conceivably hold. This apparent wind effect can be contained to some extent by flying on a very short line – basically off the bridles (about 80 meters) – when there’s enough wind to be worrying.

But the approach that has caused ray style kites to emerge as the favored shape (for now at least) is that by using through- cording instead of ribs (what Europeans call “profiles”) to connect upper and lower skins, and especially by using diagonal through-cords in selected places, it’s possible to fine tune the kite’s aerodynamic response so as to minimize pull.

This new WLK is now so finely balanced on the edge of luffing (nosing over and coming down) that even when it’s generating a ton or more tension on the main line, just one person pulling on a nose line can cause it to descend.

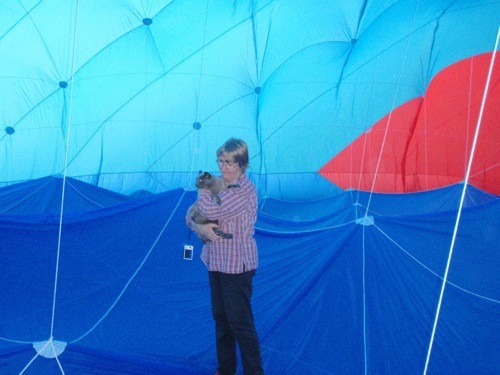

Elwyn Lynn holds Tory the cat inside the massive Peter Lynn Mega Ray.

Abdul Rahman Al Farsi, owner of the kite, and others at Berck sur mer, France, where the kite was flown in public for the first time.

But the path to this ideal state was not smooth on account of Lufthansa’s losing the 1/5th size prototype that I was using to establish these parameters in August last year. Without a model for checking dimensions, I had to make various guesses when specifying the kite’s fundamental shape (adjusting the various diagonal through-cords is for fine tuning only). And unfortunately, because in October we were informed by United Airlines that the lost prototype had been found in Brazil and returned to Lufthansa at Frankfurt, the WLK’s construction was then held back a further six weeks. I was desperate for data from the prototype so I could use more informed numbers in the design process.

Double unfortunately, Lufthansa then denied receiving the re-found kite. I suspect that by the time we supplied them with the tag numbers, names, flights, and the date it was returned to them, they’d managed to lose it again, and this time they wouldn’t have been able to hide under limited liability, so chose denial.

I did put to them the question as to who had the most incentive to lie about whether or not the lost kite had been found and returned to Frankfurt: Lufthansa or United Airlines? But they declined to answer and have required that all further correspondence be directed to one Lizette Smit in Melbourne, Australia.

By the time it became clear that the original prototype was not going to be available (another was hastily put together in time to get bridle’s lengths within the ballpark), there remained no possibility of New Zealand construction, just not enough hours in the day. So Simon Chisnal and Matt Bedford from PL Kites Ltd. took themselves off to PL Kites’ partner manufacturer, Kaixuan Kites (Tan Xinbo) in Weifang, China, and the WLK was sewn there.

And what a fantastic job they did. Minus nine degrees at times, but they are not like us gone-soft westerners. Routinely working 12 hours a day with just 3 days off a month (if you need an explanation for why China is in the ascendant, this is a good one), in less than 3 weeks it was on its way back to NZ for through-cording, bridling, and test flying. Ms. Wu, lead kite maker at Kaixuan, is the best sewing machine driver I have worked with in a lifetime of kite making.

After a week of through-cording and bridling, there were only 2 days remaining before it had to ship out of NZ again. Fortunately the wind was perfect on the first test fly day. Doubly fortunately because I was rather a long way out with some of my guesses, and it took 50 or more attempts and serial adjustment over six hours before it eventually launched and flew, just as dusk overtook us. The next day conditions were not OK. This was one of those “near run things” that you generally only read about in history books.

And it flew perfectly at its Berck public debut: firstly on Sunday, April 17th and again on Wednesday the 20th. Its stability and flying angle are like nothing I’ve ever flown before – almost vertical and like a big rock immovably fixed in the sky for hours. It needs almost no wind, probably because a useful component of lift comes from heating of the entrapped air.

But on account of insufficient testing and development time, I still have worries. The wind at Berck was steady and very light, so light that the 22 meter pilots we were using to keep the mouth open for inflation (and nothing useful flies in lighter winds than these pilots do) fell out of the sky from time to time – while the WLK stayed up.

I’m concerned as to how it will respond to apparent wind effects when there’s more wind – because even in these very light winds it generated a lot of line pull on the way up to its apex, though once up and settled it was lullingly docile.

And I’m a bit worried about how to get it down in one piece when the wind is up. Pulling even a few kg’s on the nose take- down line causes it to luff and descend, but when it gets to the ground, it typically bounces up again energetically unless the nose line is then held in tight at the kite (and this is a dangerous place to be because of all the main bridles lying around there). And worse, pulling on the take-down line with a second anchor vehicle (or, I expect, releasing the main bridles so that the kite flies off the take-down line) can cause the wings to fold up like a butterfly. It does then de-power and come down, but maybe upside down (it inverted the only time we tried this) with potential for kite damage.

The use of the side lines is also problematic. Because it flies at such a high angle, pulling on, say, the left side line causes conflicting effects: the kite is pulled to the left, and at the same time, the left wing advances, skewing the nose to the right, which resists the pull to the left. An interim solution has been to move the side anchors downwind (usually they’re rigged on a base-line at right angles to the wind direction so that they neither tighten nor loosen when the kite flies higher or lower). A better solution will be to eliminate the use of side lines entirely and use some system on the main bridle set for left-right positioning. This kite is certainly more than stable enough for this approach to work, and not having side anchors will be a big plus, especially because they won’t then have to be re- positioned every time the wind shifts a few degrees. These challenges can be addressed given time and experience – the key being to gradually increase the wind speed that it’s flown in, reviewing and developing appropriate systems step by step.

Images of the team and scene at the first public flight of Peter Lynn’s Mega Ray.

I can see no reason why this kite can’t eventually be flown safely in 40 km/hr plus, and in unstable winds (it’s so big that it barely notices turbulence). Because it’s so rock-steady, the field size needed is basically just the kite dimensions plus line length, and with a creative launching technique, it should even be possible to fly in places where the clear ground is smaller than the kite itself.

Congratulations to everyone who has made this possible: Craig, Jenny, Simon, and others at Peter Lynn Kites Ltd. The Al Farsis for being perfect customers (and friends). Andrew Beattie, the inimitable intermediary, and always bouncy. Tan Xinbo, Betty, Ms. Wu, and others at Kaixuan Kites. And Dominico Goo, the best maker of kite fabric in the world.