THE PARAKITE CONTRIBUTION TO THE EDDY KITE

Dieter Dehn

From Discourse 10

Dieter Dehn. A parakite built by author Dieter Dehn according to the instructions of Gilbert T. Woglom’s Parakites.

Until a year or so ago, the Eddy kite was a rather boring thing in my eyes. The kite is quite nice for applications and is suitable as a fast made giveaway for children or other people interested in an easy start in kite flying. Apart from this, the kite is not anything special in structure and everyone who knows anything about kites thinks he knows nearly everything about the Eddy kite and its inventor.

What we all know about the Eddy kite is:

It is a tailless kite, probably the first in the western world.

The kite frame is made of two sticks of nearly equal length crossing at 18 to 20 percent of the length of the longitudinal stick.

The cross stick is bowed or dihedral to about 10 percent of the wingspan.

There is only one thing that is often cited in the kite’s description that is not really clear: the cover of the kite should be somehow loose or wider than the frame to “bag” under wind pressure for improved stability. Unfortunately I found no description in any of my kite books that explained the meaning of a “cover somewhat wider than the frame.”

Then, when I was searching the internet for kite books of the late 19th century, I found a scan of Gilbert T. Woglom’s book Parakites. I soon learned that both Eddy and Woglom lived most of their life in rather close proximity. William Abner Eddy (Jan. 28, 1850 – Dec. 27, 1909) was born in New York and lived in Bayonne, New Jersey from 1887 on. At this time he worked in New York as an accountant at the New York Herald. Gilbert Totten Woglom (May 21, 1840 – Sep. 15, 1915) was also born in New York City and lived most of his life there. In 1863 he began a trade as a jeweler and was later one of the founders of the Jewelers’ League of New York and the Jewelers’ & Tradesmen’s Co. For Woglom, kite flying was mainly a hobby and pastime to relax from his business, or as he writes in Parakites : “ Whe n e nga ge d in t he management of a train of parakites afloat in the air, one gives no thought to stocks, finance, the store, his profession or his quest for the elusive dollar. Were more men thus engaged in restful work we would hear less of paresis, heart-failure, and Bright’s disease in these days of over-active business men.” [Note: Paresis is a condition typified by partial loss of movement. Bright’s disease is a historical classification of kidney diseases.] Both Woglom and Eddy flew their kites on different occasions from buildings in New York City. One of these events was the “Sound Money Parade” of October 30, 1896, when they flew their kites at the same time not much more than a mile apart.

In 1896, Gilbert T. Woglom published his book Parakites – A Treatise on the Making and Flying of Tailless Kites for Scientific Purposes and for Recreation. Here we find a detailed description of a “parakite:”

It is a tailless kite.

The kite-frame is made of two sticks of equal length crossing at 17 percent of the length of the longitudinal stick.

The cross stick is bowed to a depth of 10 percent of the wingspan.

For improved stability the cover of the kite is 10 percent wider than the frame and folded in “box plaits” along the spine to form two concave surfaces under the pressure of the wind.

This sounds very much like the description of the Eddy kite but with more precise specifications. As in my opinion this must have been more than pure coincidence, I began to look for all possible information about Eddy, Woglom, and the New York “kite scene” of the last ten years of the 19th century. With all the facts I found from different sources, I then began to build some kind of timeline:

1891 to 1894: After some unsatisfactory experiments with trains of classic American flat kites, W. A. Eddy develops a tailless bowed kite based on information about Asian kites.

1894 and 1895: Eddy visits the Blue Hill Observatory in Massachusetts. He makes experiments to lift meteorological instruments and on August 4, 1894, he reaches a height of 1430 feet with a train of kites carrying a thermograph.

Up to 1895: G. T. Woglom develops his “parakite” based on information about Oriental kites he has gathered (and written down in his book).

May 4, 1895: At the dedication of the Washington Arch in New York City, Woglom lifts a 10 foot US flag on the line of a train of parakites that he flies from the tower of the Judson Memorial.

May 30, 1895: With a 3 1/2” x 3 1/2” (9×9 cm) Kodak roll film camera lifted by a train of his kites, Eddy takes his first aerial photos.

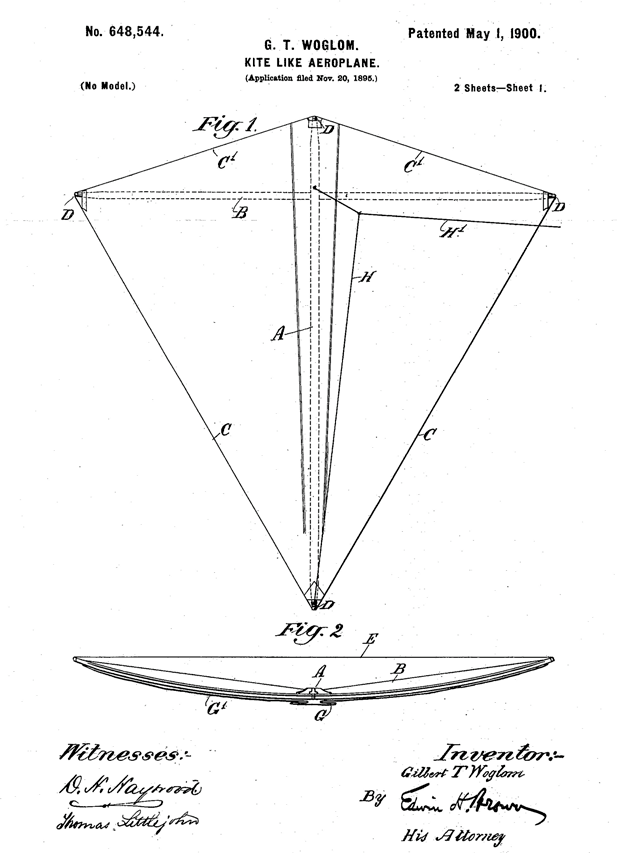

Nov. 20, 1895: Woglom applies for a patent for his parakite as “Kite Like Aeroplane.”

1896: Woglom publishes his book Parakites.

1895 to 1898: Eddy makes different experiments to show the use of his kites, including more aerial photography, lifting flags or lights as

signals, or towing buoys across the water (in cooperation with John Woodbridge Davis).

Nov. 24, 1896: Eddy applies for a patent for his camera rig, approved March 16, 1897 as US patent 578,980.

Aug. 1, 1898: Eddy applies for a patent for his kite.

March 27, 1900: 1 year and 8 months after the application, Eddy receives US patent 646,375 for his kite.

May 1, 1900: More than 4 1/2 years after the application, US patent 648,544 is approved for Gilbert T. Woglom’s kite.

A picture of the Woglom parakite from his book, Parakites.

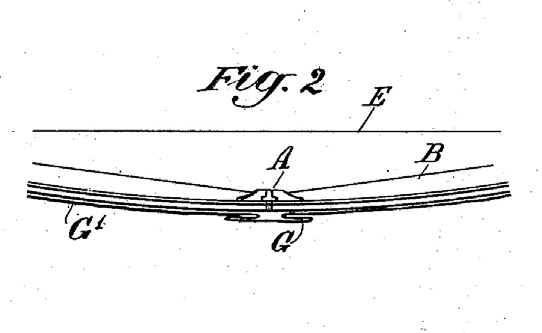

Woglom’s patent drawing for US patent 658.544, showing front and top views of the kite.

Apart from the long difference in time from application to approval of the two kite patents, this timetable shows the parallel development of two rather similar kites. How very close these parallels were, I found out on closer examination of certain points of this timeline.

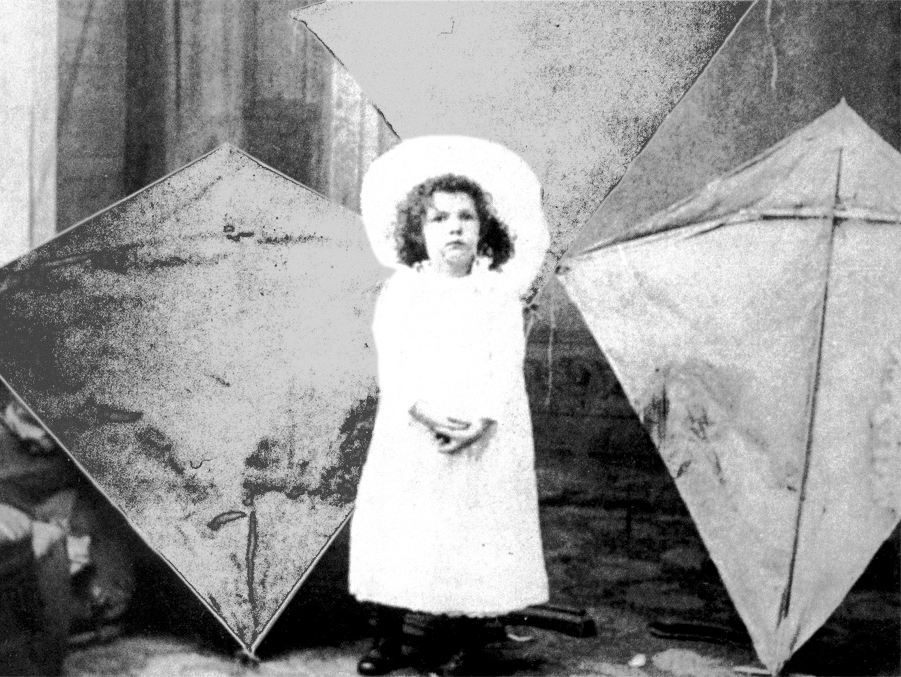

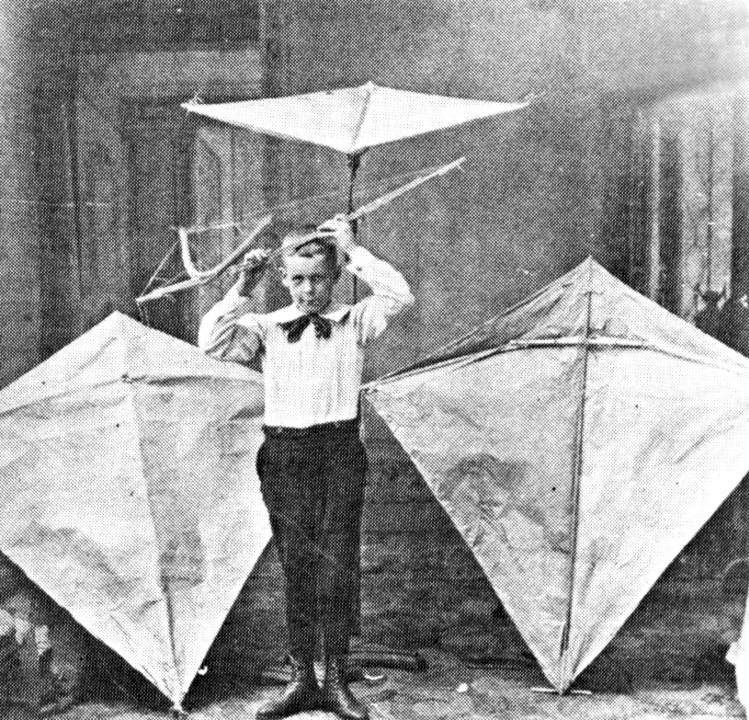

When looking for information about W. A. Eddy, there is one photograph that can be found at different places on the internet: the picture shows Margaret Eddy, the daughter of W. A. Eddy, together with some of her father’s kites. In all sources, this photo is dated to the year 1895. A second picture, obviously taken at the same occasion, shows an unnamed boy holding up a kite frame. We can assume that these two pictures show a part of Eddy’s stock of kites in 1895. When we take a closer look at these kites, we can see that the kite sticks are crossed at about 18 to 19 percent of the kite’s length, as written in the “recipe” for an Eddy kite, but we can also see that the end of the cross-stick is not only bent backwards but also downwards. Thus the edges of the kite are not in the 18 percent range but at about 32 percent of the kite’s length. This fact can be observed especially at the “naked” frame the boy is holding in the second picture. As a conclusion, the Eddy kite of 1895 still shows a lot of its Oriental ancestor’s attributes.

In the same year, Gilbert T. Woglom appears in public as a kite flier. On the 4th of May, he flies a train of kites carrying a big flag from the tower of the Judson Memorial Church over Washington Square. With this “special” on the occasion of the dedication of the Washington Arch, he is part of the news of the day and known as a kite specialist from then on. In November, he applies for a patent for his “Kite Like Aeroplane.” In the text and the drawings of this patent, Woglom gives the full specification of his parakite as published in his book, with the only exception that in the patent he recommends the sticks be crossing at 15 percent, while in the book it is 17 percent. In particular, the patent contains exact recommendations on the size of the kite cover (10 percent wider than the frame) and how it is folded as a “box plait” along the longitudinal axis of the kite (clearly shown in his patent drawing at letter “G,” pictured below).

At the same time, W. A. Eddy exchanges letters with James Means, the publisher of the Aeronautical Annual. In two letters of December 1895, Eddy describes “the best Eddy kite for winds above 6 miles per hour, for the season of 1895.” In this description we can find the remark: “The paper should be gathered on a box pleat from A to E. This causes concavity along the central upright,” and sketches of this pleat that show great resemblance to Woglom’s patent drawings.

Margaret Eddy with her father’s kites. Photo taken ca. 1895.

Boy with the frame of an Eddy kite. Photo is obviously taken at the same occasion as the photo at left.

Eddy concludes that the pleat “is at times of considerable assistance in enabling the kite to withstand very high winds but that is only of use to a specialist who is working at difficult phases of the problem.” With these notes, the “box pleat” appeared in Eddy’s kite descriptions but apparently was put aside again very fast.

After a number of occasions when Eddy and Woglom showed their kite experiments to the public, the next important contact of their “ kite lines” is Eddy’s patent application. Two years and nine month after G. T. Woglom’s application, Eddy writes down the specification of his kite. Here we can find the source of the Eddy mystery, the cover that is wider than the frame: “…This cover is made, preferably, of suitable flexible material, such as cloth, and while in shape conforming substantially to the lines connecting the ends of the frame-pieces is wider along the line of the cross-bar than the length of the cross-bar.” We can also find the instruction that “…the greater width of the cover is taken up by gathers or folds along the portions of the wires or guys which run to the top of the kite…” That does not really help our problem, but so far we have only looked at the general description of the invention. The important part of a patent are the claims. The first two claims are about the kite cover that is “wider than the frame secured along said guys and gathered near the medial line of the frame” and the bowed cross stick. Claims 3 to 9 deal with variations of the first claims and details of the fittings for the crossing and tips of the sticks. The 10th and last claim seems to be a summing up of the previous and differs from the others a bit in size and complexity:

“10. In a kite of the character described, the combination of crossed extender members, guys passing there-around to produce a symmetrical frame, a covering secured upon

the frame, and means upon the covering whereby under the action of the wind said covering is adapted to have formed in it two concavities extending longitudinally of the upright extender member, substantially as specified.”

The italics are added by me to highlight a fact that attracted my attention. When I read this text it sounded somehow familiar to me. I went back to the Woglom patent and found the following claim:

“Having described my invention, what I consider as new, and desire to secure by Letters Patent, is –

1. In an object of the character described, the combination of extender members and guys cooperating to form a symmetrical frame and a covering secured to said guys, said covering being provided with a longitudinally-extending double fold or box-plait at its middle portion, so that when the covering is under the action of the wind it will have formed in it two concavities extending longitudinally of the upright extender member, substantially as described.”

Again I highlighted some words as before. Comparing these highlighted parts of the text, it can be seen that these two patent claims are virtually identical. Obviously either Eddy or his patent attorney knew the text of Woglom’s patent too well to get it out of the mind. Nowadays the effect of this similarity of patent claims would be that the patent that had been applied last would be of very questionable worth.

The next witness of the connection between the Eddy kite and the Woglom parakite dates from somewhere between 1898 and 1900, and this time it is not only paper but the real thing. Rather early in my investigations about William A. Eddy, I found an article in the Drachen Foundation Kite Journal of Fall 2001. In this article, Eden Maxwell describes his visit to the National Air and Space Museum in Was hingt on. Her e , in t he Gar ber preservation and restoration facility, one of the last original Eddy kites is stored. According to the label on the sail naming it “War Kite,” this kite surely is none of Eddy’s “homemade” kites, but must be one of those that have been manufactured by E. I. Horsman in New York. The size of the kite corresponds to the standard recipe of an Eddy kite, length is 61” (1550 mm), cross- stick is 60” (1537 mm), sticks cross at 19 percent of length, the cross stick is bowed to approximately 10 percent of the span. The frame and the fittings are, apart from insignificant modifications, as shown in Eddy’s patent drawings. So far, there is nothing wrong, but when we have a close look at the picture showing the top end of the kite, we can see a nice pleat sewn in the cover on either side of the spine, as below.

Eden Maxwell. To express it in a somewhat extreme way, here we can see William A. Eddy’s answer to our question of how to fix the cover that is wider than the frame: we take Eddy’s kite frame and combine it with the cover of Woglom’s parakite!

Nevertheless, apparently all this had no effect on the personal relations between Eddy and Woglom. In all the newspaper articles, notes, and letters to the editor I found, neither of the two wrote anything about plagiarism. The only controversy was about the taking of the first kite aerial photograph. Woglom wrote in his book that on September 2, 1895, he had taken the first aerial photo on a glass plate with the help of a kite, not mentioning that W. A. Eddy took his first photos on May 30 of the same year using his Kodak roll-film camera. The relationship between the two kite fliers must have been so good in the end that in an article of the New York Herald of February 23, 1900 about a gathering of the Woglum (Woglom) Family under the headline “ONE WAS A KITE FLYER,” we can find the passage:

“Gilbert Totten Woglom was the first scientific kite flyer in New York. He is now associated with Mr. Eddy, of New Jersey, in experimenting with kites. He was at yesterday’s reception.”

In 1900, at the end of our little trip through the 1890s, the Eddy/Woglom kite was at the peak of its evolution. There was not much impulse for further development, for the “professional” kite fliers had turned to box kites, and the Eddy kite was left to amateurs and children. So, over the years, this kite lost a lot of its old refinement and became what I stated at the beginning of this text: nothing special, sometimes even boring.

In addition to confirming that there is nothing boring in historical kites, for me, all my research on this subject showed again: it always pays to look a second time, look at something else, learn something else, and than have a third look at your first object. With your new knowledge, your third look will reveal new things to you that had been there all the time. for, as J. W. v. Goethe said, “You only see what you know.”