Copyright © 1981 by Guy D. Aydlett Dear Kiteflier:

Our first DATA-LETTER (Vol. 1, No. 1, December 1980) included a list of rotor-kite patents that has raised some questions from all three of our readers. The most popular query is: Where can a creative kitist find or buy patents for study? Answer: First , try out your public library; especially if you live in—or near—a large city. Ask for the Reference Librarian. Other sources are special libraries within corporations that maintain patent files for the convenience of engineering and scientific employees. If you work in such a place, its library or its patent department might be able to help you. When all else fails , write to the Commission¬er of Patents and Trademarks, Washington D. C_. 20231; order the patents you want by number. Include 500 for each invention patent , 200 for each design patent. Plant patents—unlikely to be of interest to aero-vanists—are sold for $1.00 each. Send a valid money-order, a cashier’s check, or a certified personal check ; otherwise , you may have to wait—and wait—and wait—for the delivery of your order. Order a mini¬mum of $1.00 worth of patents. (Do not bother to tell the Commissioner why you want copies of patents; he’ll probably be on vacation, and an uninterested clerk will be filling your order.) Never curse if

the patent prices mentioned here are incor¬rect at the time when you place your order; Government prices are always subject to change without notice.

We recommend Donald M. Dible’s book to anyone who’d like to gage the arcanery of patents, trademarks, and copyrights—What Everybody Should Know About Patents, Trademarks and Copyrights. (Fairfield , California: The Entrepreneur Press , 1978 ; price, $4.95 ). The Poor and The Thrifty might haunt their libraries in hopes of find¬ing Dible’s Book.

Patents expire after they have been in existence seventeen years, according to the books. The inventions then enter the public domain ; that is, owners of expired patents no longer enjoy Government-granted rights “to exclude others from making, using, or selling the invention [sl .” (The “rights to

exclude” are all that the patent-holders get for their money. Their letters-patent do not grant any of the owners specific rights to make, use, or sell their own inventions.)

If you choose to raid the public domain in order to loft—or lift—the great Airy Disk Optical Kite invented in 1963 by Beauforce Stringfellow , be fair to his genius and givehim credit for the creation that gives you fun or profit. Be true to thine own ego.

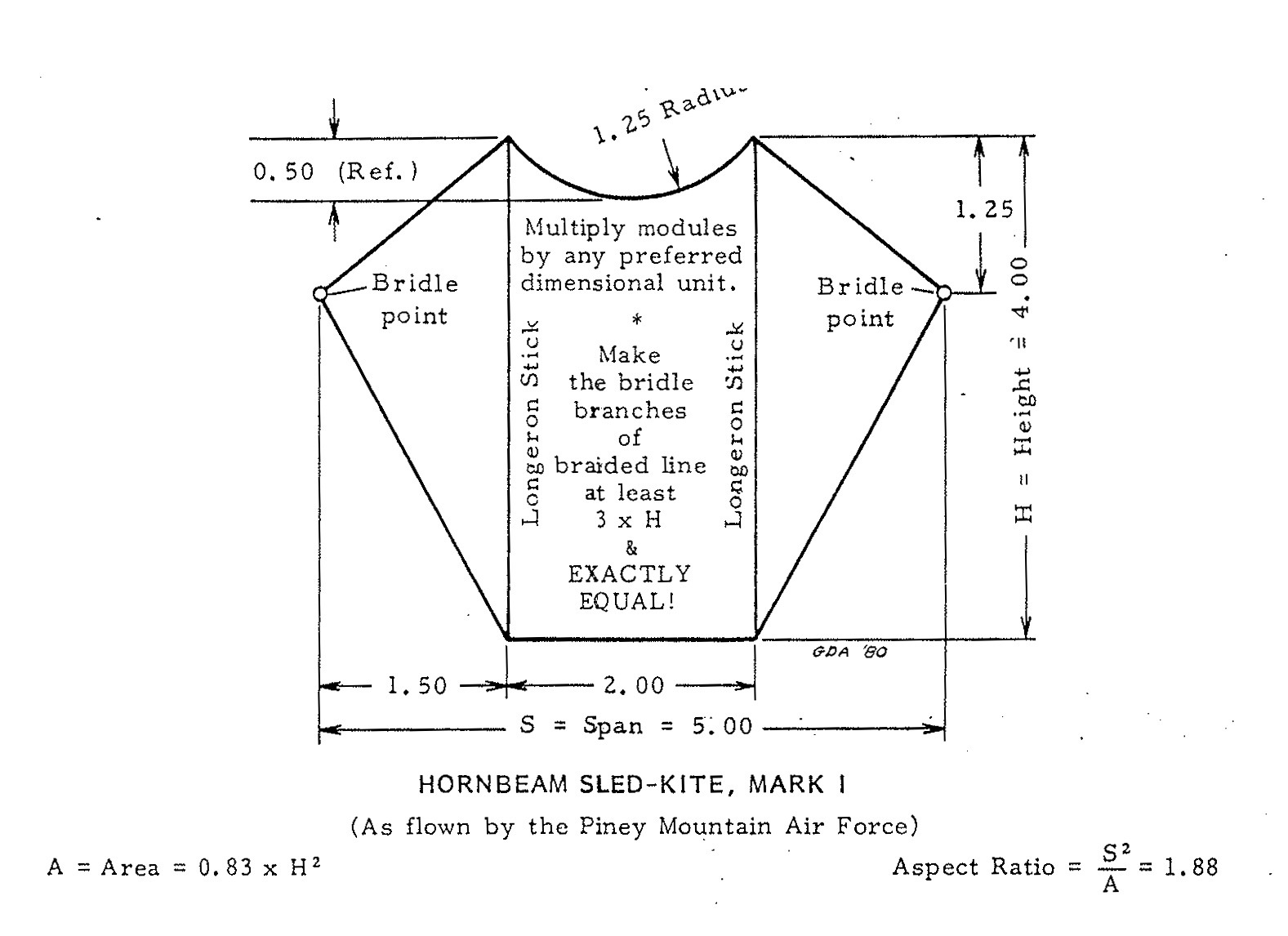

HORNBEAM SLED-KITE, MARK I

In our first issue of DATA-LETTER , we promised to tell about “The Hornbeam ,” a kite design that is a logical refinement of William M. Allison’s “Flexible Kite,” U.S. Patent No. 2,737,360, March 6, 1956. The name “sled,” or “sled-kite,” is said to have been coined by Frank Scott, son of “Sir” Walter Scott (both frequently mentioned in old issues of Bob Ingraham’s Kite Tales).

Bill Allison launched a tradition on thatgreat day when he lofted his first flexible kite. His invention was so easy to copy or modify, it is doubtful that his inspired cre-ation significantly fattened his fortune; but his kite has enriched the lives of thousands of kitefliers with boundless pleasure.

In these days , few of the original Alli¬son configurations are to be seen. As his patent reveals, the kite was constructed with three longitudinal stiffeners: one on the centerline bracketed by two outboard longerons angled slightly out of parallelism with the one in the center. This splaying caused the kite, in flight, to assume a con¬oidal form that diminished towards the rear, or trailing edge, and caused a state of in¬flation pressure that minimized incipient collapsing tendencies. Its only drawback, compared to kites with parallel longerons, was the difficulty of rolling it up smoothly for storage or transportation. Kites rigged with parallel sticks tended to have grievous stability and collapse problems; but many ambitious geometers adopted a popular cor-rective effort that involved deflowering the poor things with fanciful perforations, ap-ertures, holes, and fenestrations.

Hornbeam Thatch, doyen of pendulum clock horologists, solved the problems by changing the kite plan form, or perimeter, in a way that would induce beneficial, di¬verging airflow at the mid-section of the leading edge. Hornbeam made his discovery on the frost-rimed flightpad of Monroe Com¬munity College, Rochester, New York, in the early spring of 1976. One of a gaggle of sleds in wondrous planforms was flying poorly; lurching, snapping, and popping.

0. 50 (Ref. )

Its leading edge mid-section puckered and sagged into a rough arc (the kite had no centered Ion geron) ; immediately , the kite steadied and climbed well even though it was hampered by the wind-drag of the de-ranged portion of the Tyvek® canopy.

Hornbeam watched the rumpled marvel, tenderly grounded the configuration , and removed the pleated crescent with his finely honed stock-knife. Following the rabbinical paring, the kite continued to fly well.

Except for some minor refinements, the “Hornbeam” diagrammed on this page has proportions nearly identical to those of that altered flier that once flogged the frigid air over Rochester.

Fly Hornbeam in the air over your pad; afterwards, you may give up hole-cutting.

A FRIENDLY CHALLENGE ; Try Hornbeam ; if you don’t believe it’s the best sled design you’ve made or flown, send us your favorite, or a good drawing of it. If we agree with you, we’ll make great efforts to immortalize your design in a future issue of DATA-LETTER

PINEY MOUNTAIN AM FORCE DATA-LETTER

By First Class Mail in the U.S.A. : $7. 50 per year, or 750 per copy

Send check or money order (no cash) to:

Guy D. Aydlett

Post Office Box 7304

Clariotte’sville VA 22906