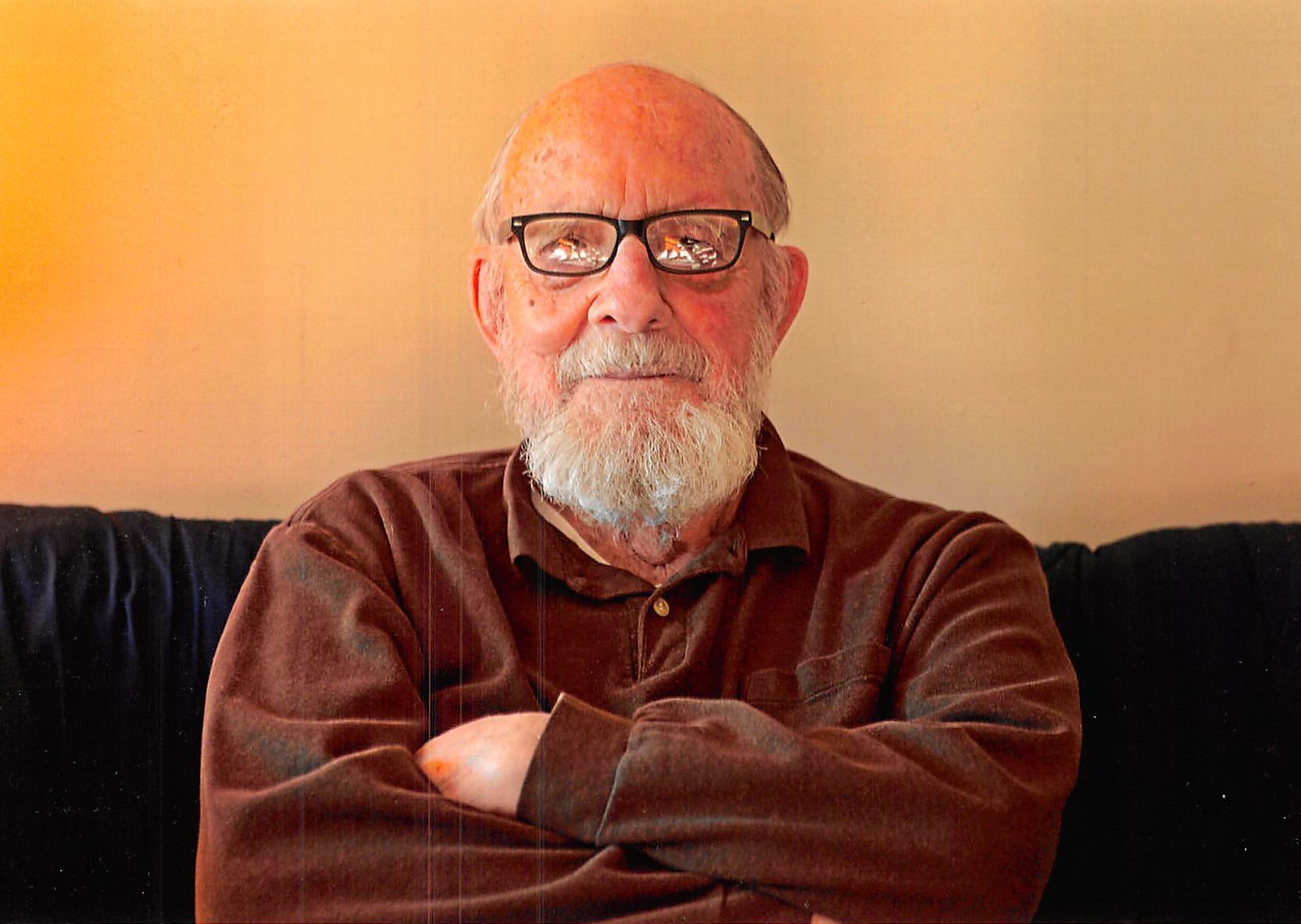

ON THE COVER:

One of Colorado artist Melanie Walker’s beautiful kites. More on page 23.

Drachen Foundation does not own rights to any of the articles or photographs within, unless stated. Authors and photographers retain all rights to their work. We thank them for granting us permission to share it here. If you would like to request permission to reprint an article, please contact us at discourse@drachen.org, and we will get you in touch with the author.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

APRIL 2016

- From the Editors

- Correspondence

- Contributors

- Interview with LaRoy Rutledge JOE HADZICKI

- Interview with Malcolm Goodman SCOTT SKINNER

- Interview with Ben Ruhe SCOTT SKINNER

- Interview with Melanie Walker ALI FUJINO

- The Surubí: A Creative Context MARIA ELENA GARCÍA AUTINO

- Tribute to Charlie Sotich JOHN BRAZZALE

EDITORS

Scott Skinner

Ali Fujino

Katie Davis

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Scott Skinner

Martin Lester

Joe Hadzicki

Stuart Allen

Dave Lang

Jose Sainz

Ali Fujino

BOARD OF DIRECTORS EMERITUS

Bonnie Wright

Wayne Wilson

Keith Yoshida

Drachen Foundation is a non-profit 501(c)(3) corporation devoted to the increase and diffusion of knowledge about kites worldwide.

Discourse is published on the Drachen Foundation website several times a year and can be downloaded free at www.drachen.org (under Browse > Articles).

FROM THE EDITORS

This is a very personal issue of Discourse. The bulk of the issue is interviews of various personalities from our diverse world of kites. I found that there were several statements that struck a chord with me, and perhaps that is the best way for me to introduce this issue.

In Joe Hadzicki’s conversation with foil- boarding pioneer LaRoy Rutledge, I love his admonition, “Don’t take someone’s opinion as the answer. Explore the details and shape the approach that works best for you.” In sport, art, and life, I think this is a powerful attitude. It makes your best result the one crafted specifically by you, for you.

Malcolm Goodman, English kite promoter, collector, authority, and world traveler, has interests that run parallel to many of my own, and I was struck at how his journey deep into the world of kites was sparked by some of the same people who influenced me. His first trip to China was organized by Seattle’s Dave Checkley, a man who introduced so many of us to Japanese and Chinese kites. Malcolm says, “Tal Streeter was also on the tour, which made it even more magical and educational. I returned home after six weeks with many oriental kites that I still treasure to this day, and I felt that my life had changed forever.” I hope that we are making this sort of impression on new participants in the kite scene.

You’ll notice that my interview with Ben Ruhe is less structured than others. This is a result of my enjoyment in simply talking with Ben. It just doesn’t seem appropriate to try to formalize a conversation with Ben. I loved learning more about his childhood and family life, but was struck that in all the experiences with Drachen, it was people like Curt Asker, Jackie Matisse, Istvan Bodoczky and the Texas Tech team of bill lockhart and Betty Street who he remembers the most.

I live less than 90 miles from Melanie Walker (and George Peters) and I think in the last 30 years we’ve flown kites together in Colorado fewer than five times. I love hearing Melanie’s motivations and fascinations. “I love making the visions I see in my head and turning them into something out in the world, I love being able to see and feel the wind. Making ideas that can literally fly.” Melanie’s body of work continues to grow in surprising and beautiful ways. (One of her clouds is at the top of my “favorite kites” list.)

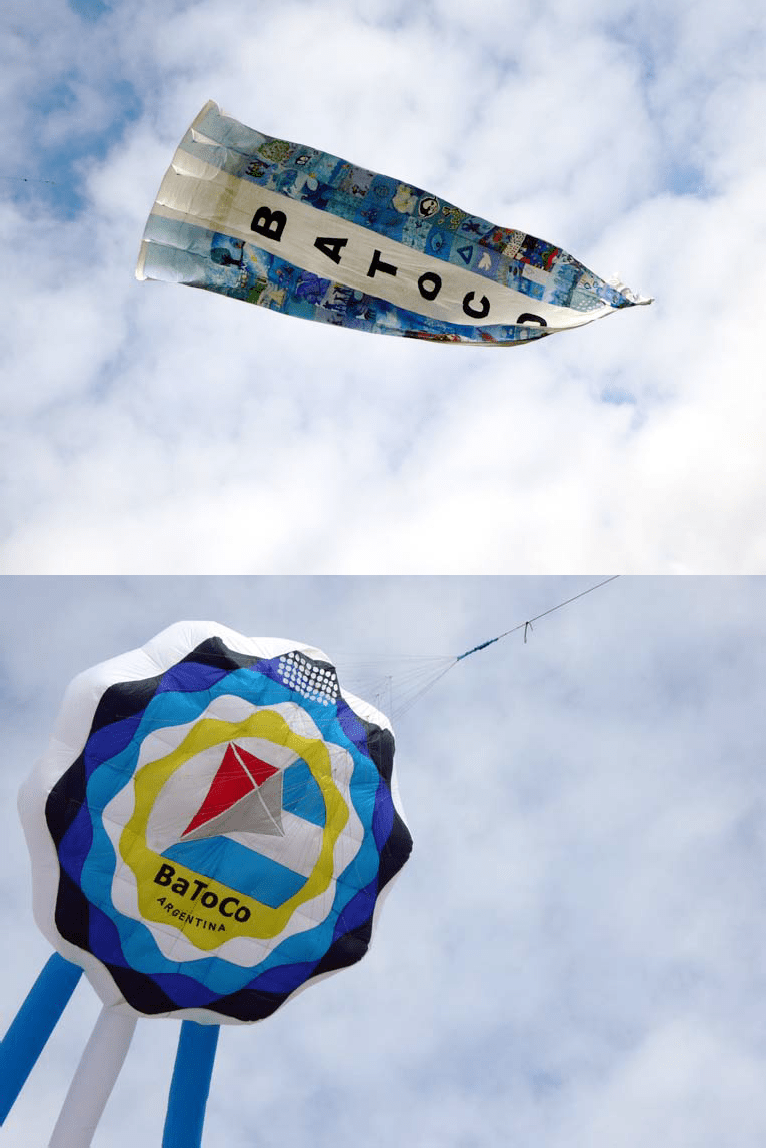

Finally, contributor Maria Elena García Autino brings us up to date with many of the collaborative Barriletes a Todo Costa (BaToCo) projects. She eloquently states, “I aim to emphasize the importance of a ‘context of participation’ that transcends the activity of a human group and advances on the public sphere, enhancing it.” These projects are about much more than the objects created; they are gatherings that bring together diverse individuals and groups and make them into a community. Marie Elana and BaToCo’s projects are models for all of us in our own corners of the kite world.

My thanks to Drachen Foundation board members Joe Hadzicki and Ali Fujino for their work on this issue. Not to mention great editorial work by Laurie Leak and final organization and layout by Katie Davis. You all make it happen!

Scott Skinner

Board President

Drachen Foundation

CORRESPONDENCE

Another great newsletter and Discourse.

GARY HINZE

USA

Thank you for this issue. I love what Steffi was writing about her work and her resume about what’s going on meeting together.

KISA SAUER

Germany

I could not have wished for a better review! It captures the purpose and essence of the book wonderfully. Thank you very much indeed.

JOHN BROWNING

USA

Good work, well done!

STEPHANIE RAUCHWARTER

Austria

CONTRIBUTORS

Courtesy John Brazzale

JOHN BRAZZALE

Chicago, IL

The nephew of Charlie Sotich, Brazzale is Chief Administrative Officer for Corporate Banking at Northern Trust Company and Chair of the finance and investment committees on the national board of Rebuilding Together in Washington, DC.

Drachen Foundation

ALI FUJINO

Seattle, Washington

From work at the Smithsonian to her present status as Director of Advancement for the Alaska Wilderness League, Fujino continues her 24 years with the Drachen Foundation by serving on Drachen’s Board of Directors.

Jorge Oswald

MARIA ELENA GARCÍA AUTINO

Buenos Aires, Argentina

A Barriletes a Toda Costa (BaToCo) member, Autino is a retired professor who taught for many years at the University of Buenos Aires. She has won national and international awards for her work in education.

Kirsten Hadzicki

JOE HADZICKI

San Diego, California

An engineer, inventor, and entrepreneur, Hadzicki is one of three brothers who started Revolution Enterprises, the first to make a completely controllable four-line kite. The Rev has been the standard for the kite industry for over 20 years.

Courtesy of Scott Skinner

SCOTT SKINNER

Monument, Colorado

A former Air Force instructor pilot, Drachen’s board president has flown and designed kites for three decades. Today, Skinner is known as a world class, visionary kite artist.

Articles

- From the Editors

- Correspondence

- Contributors

- Interview with LaRoy Rutledge JOE HADZICKI

- Interview with Malcolm Goodman SCOTT SKINNER

- Interview with Ben Ruhe SCOTT SKINNER

- Interview with Melanie Walker ALI FUJINO

- The Surubí: A Creative Context MARIA ELENA GARCÍA AUTINO

- Tribute to Charlie Sotich JOHN BRAZZALE

INTERVIEW WITH LAROY RUTLEDGE

Joe Hadzicki

Joe Hadzicki. “Kiteboarding is life for me. I love it, I feel it, I sense it. It’s where I belong.” – LaRoy Rutledge

There is a whole range of radical, recreational sports dependent upon excellent kite flying skills: kite buggying, snow kiting, hang gliding, and paragliding, to name just a few. One of the fastest growing water sports in the U.S. is foilboarding (also known as hydrofoil kiteboarding), an extreme segment of kiteboarding. In place of a flat kiteboard, picture a small surfboard with a carbon fiber wing attached one meter below it. At speed, the wing lifts the rider and the board a couple of feet above the water, creating a virtual “magic carpet” ride. The first foilboards were towed behind boats or jet skis (think surfer Laird Hamilton: www.youtube.com/watch?v=N01vrLwAWiM), but in recent years kiteboarders have adopted their use. Using kites in place of motorized watercraft, foilboarders are able to glide through the water with reduced friction, reach higher speeds, and kiteboard in lighter conditions than ever before.

Foilboards have taken this sport to a whole different level. The sport is gaining in popularity because it is so efficient, allowing riders to go fast with very little wind – perhaps twenty knots across the water in winds of only six or seven knots! But it also requires the rider to have very good and precise kite flying skills.

A local hero in the San Diego kiteboarding community, LaRoy Rutledge, is an inspiration to many younger riders and is generous with his help and advice to newbies. He’s ridden with the best in a whole host of sports from drag racing to surfing, and from snowboarding to kiteboarding. LaRoy is passionate about foilboarding, which he discovered two years ago. Though he has high level skills, he also has a common sense attitude and the ability to relate to the beginning foilboarder. He emphasizes how important it is to be able to fly instinctually and have mastery of safety systems for all kinds of situations because things can get dangerous quickly.

Top: Joe Hadzicki. Bottom: LaRoy Rutledge. Local San Diego kiteboarding hero LaRoy Rutledge and his hand-built board and hydrofoil set up.

I recently sat down with LaRoy to get his take on kiting and the challenging sport of foilboarding.

LAROY, YOU’RE A LEGEND IN THE SAN DIEGO KITEBOARDING COMMUNITY. WHAT MAKES YOUR EXPERIENCE UNIQUE?

I’m driven. I will not give up. I can’t accept failure. Expertise with the wind is not as important as being obsessive.

HOW DID YOU GET TO WHERE YOU ARE TODAY?

When I was a little kid, I stopped by a small town airport just to look around. A man tapped me on the shoulder and asked me if I wanted to go for a ride in his plane. My mother would have had a fit if she had known! Not only did it change my life by introducing me to flying, but it gave me a whole new perspective. The telephone poles below looked like matchsticks! I realized that things aren’t always as they seem. At that point I realized when you’re learning something new like a sport, don’t take someone’s opinion as the answer. Explore the details and shape the approach that works best for you. I later went on to join the Army and became a helicopter pilot in the 101st Airborne Division. I love the Army’s motto, “Be all that you can be.”

TELL US ABOUT YOUR EXPERIENCES IN THE KITE WORLD.

I started flying kites in 2000. It was the most alien thing I had ever put my hands on. Now, however, a kite is like a machine and I know exactly where to put it. My first kite was an Airush two-line, 1.5 meter trainer kite. Then I flew a nine meter, ram air, four- line Quadrafoil before being sponsored by Peter Lynn through a local kite shop. I recognized Peter as a leader and visionary in the kite world. My first Peter Lynn kite was the S-ARC, followed by the F-ARC and the Venom.

WHAT ADVICE DO YOU HAVE FOR BEGINNING FOILBOARDERS?

Foilboarding is the most physics-related sport I’ve ever done. Take a lesson from someone who knows how to teach, and then focus on one thing at a time. You have to learn and perfect one thing at a time. It’s all about balance, leverage, and weight.

YOU ARE KNOWN FOR MAKING YOUR OWN FOILBOARDING EQUIPMENT. WHERE DO YOU FIND YOUR INSPIRATION?

My designs come from nature. Nature has all the answers. Look at the fastest fish. You can see the shape of it – that’s what you want to do. The new foil wings are shaped just like seagull wings.

WHAT HAS KITEBOARDING TAUGHT YOU ABOUT LIFE?

Kiteboarding is life for me. I love it, I feel it, I sense it. It’s where I belong. I’m precisely where I should be based on the decisions I’ve made in my life – from a skateboard, to a surfboard, to a snowboard, to a foilboard. That’s how I got here. I want to get the most out of it that I can. Not to be the best guy, but to be the best that I can be. I was once asked by someone, “How can I end up like you?” My response was, “You can do anything if you don’t accept failure.” ◆

INTERVIEW WITH MALCOLM GOODMAN

Scott Skinner

Goodman Collection photographs and descriptions by Malcolm Goodman

TOMOE DAKO 1. Made by Matsutaro Yanase of Shizuoka Prefecture.. Kindly given to me by three young kitemakers who took me and my wife Jeanette sightseeing and to visit kitemaker Mrs. Kato and view Mt. Fuji in 1997.

CAN YOU TELL US HOW LONG YOU’VE BEEN INVOLVED IN KITE FLYING AND ABOUT YOUR LIFE IN ENGLAND BEFORE KITES?

My attraction to wind and flight began early in childhood. Like many of us, I recall making and flying brown paper diamond kites with my father, but the pastime did not grab me and I put it aside, as in my early teens I was more interested in crystal sets and short wave radios. I left school at 14 without any qualifications. I was diagnosed later in life as having dyslexia.

I became an apprentice at a radio and hi-fi shop and at 19 was headhunted to be the Service Manager/Engineer for a chain of camera, hi-fi, and TV shops where I was trained in electronics by Sony, Bang & Olufsen, and many other well-known brands.

YOU HAVE A BACKGROUND IN LAND SAILING, DON’T YOU? DO YOU KEEP AN EYE ON MORE EXTREME FORMS OF KITING: KITE SURFING, KITE BUGGYING, KITE SAILING, OR ENERGY GENERATION?

In the 70s I became seriously interested in land yachting, racing and competing across the United Kingdom, and I also went to Northern Ireland where I won the Class 3 Championship. Like kiting, land yachting is a wind-dependent sport and I realized that when waiting around for the wind to pick up I needed something to do.

The answer: Peter Powell had just introduced his stunt kites, but as I couldn’t afford to buy one I found a cheaper two-line kite from America called a “Barnstormer.” This was similar to a Peter Powell kite but made from thinner plastic and wooden dowelling. It was made by Mattel, the toy company.

YAKKO DAKO (MEDIUM) 1. Made by kite master Mikio Toki who is recognized around the world as one of Japan’s best kite artists. He cuts and shapes the bamboo frame and beautifully paints the decoration onto the washi paper.

NAGASAKI HATA DAKO 1. A Japanese fighter kite beautifully made by kite master Seiko Nakamura, one of the best hata kitemakers in Japan. He won Kite Master of the Year with this kite.

ABU DAKO. Abu means horse fly. The sleeve wings provide stability.

I also became interested in hang gliding. I progressed well, but after a serious crash I switched to parascending. Once again it was the serious accident of a close friend that made me give up this hobby and concentrate on kiting and keeping my feet on the ground!

I take a keen interest in any new developments in wind energy. Wind energy is now being harnessed, but there is a long way to go!

CAN YOU TALK ABOUT YOUR KITE COLLECTION AND THE INTERNATIONAL TRAVELS THAT HELPED TO FORM IT?

In 1976 I went on a holiday to San Francisco and Seattle, and near Pier 39 I saw people flying single-line kites. I was so impressed with them and while in Seattle I joined the local kite club (West Coast Kite Fliers?), mainly to receive information about kiting developments. I also bought my first “oriental” kite from the Kathy Goodwin kite store. When I returned to England I made a simple kite and happily for me it flew the first time.

In 1982 I read in the Seattle club newsletter that Dave Checkley was arranging a trip to Japan to visit the Hamamatsu and Chiba kite festivals. I wrote to the club and asked if I could join them. They said yes, so I remortgaged my house to pay for the trip. While the trip was being planned the group was invited to China by the Peking Kite Institute, as kite flying was restarting after being banned during the Cultural Revolution. They wanted to know about western kites and the materials we used.

This was my first trip to the Far East and I fell in love with the kites and the people. I also realized that most of the kite masters in both Japan and China were getting old and had no apprentices to carry on the traditional skills. That’s when I decided to start collecting oriental kites so that future generations would be able to see these beautiful works of art.

Tal Streeter was also on the tour, which made it even more magical and educational. I returned home after six weeks with many oriental kites that I still treasure to this day, and I felt that my life had changed forever. Since those early days, my wife, Jeanette, and I have been lucky enough to travel extensively throughout the Far East and have amassed a comprehensive collection of oriental kites.

WITH THE RECENT PASSING OF STUNT KITE MAKER PETER POWELL, CAN YOU TALK ABOUT ANY EARLY INTERACTIONS YOU MIGHT HAVE HAD WITH HIM, HOW YOU VIEW HIS ROLE IN INTERNATIONAL KITING?

I met Peter around 1978 at kite festivals in the south of England, and I invited him to many of the kite festivals I organized in the north of England. He was a t rue “showman,” always immaculately dressed in a suit and tie. It didn’t matter what the weather was doing, Peter was always able to put on a wonderful performance.

His best trick was being driven around the arena in either an open top car or him standing on the back seat of a car with his head and shoulders through the open sun roof flying a stack of three kites. I think Peter more than anyone else was responsible for introducing so many people in the western world to kiting and making it acceptable for adults to fly and make kites and kites not to be thought of only as a child’s toy.

BUKA DAKO 1. Size 40 cm x 26 cm. Bamboo and washi paper.

UNFINISHED FUKUSUKE DAKO. By Semmatsu Iwase of Aichi Prefecture. Fukusuke is a large- headed dwarf, a symbol of good luck and prosperity. Given to me by Semmatsu-san when visiting him in 1989.

ME WITH TWO NAGOYA KORYU DAKOS. Made in Nagoya. The old bamboo used will have come from the roof of a very old house. Over the years the bamboo was turned a beautiful brown. These kite are very rare as they take a lot of skill and time to make and are never sold.

ANY OTHERS WHO ARE RECENTLY DECEASED WHO YOU THINK FORMED THE LANDSCAPE OF ENGLISH KITING?

Jilly Pelham, Alec Pearson, Ron Moulton, Clive Hart, David Turner, Peter Powell – there may be others but I knew most of the above personally.

TALK ABOUT YOUR INVOLVEMENT IN KITE FESTIVALS AND YOUR OPINION OF THE HEALTH AND WELL-BEING OF FESTIVALS IN GREAT BRITAIN.

After returning from a kite festival in 1986, I did an interview on local TV. Shortly after I received a call from an Arts Center that was organizing an Anglo/Japanese Festival. They asked if I could organize a kite festival as just one part of the event. I said yes, and it was a great success with kitefliers from all corners of the world attending. Over the next 20 years in which I was involved, it became known as the Sunderland International Kite Festival and regularly attracted over 50,000 spectators. The public and kitefliers alike thoroughly enjoyed the festival.

I have organized many more festivals in all parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland, but sadly due to the economic situation over the past years it has been very difficult getting sponsorship for kite events. Two or three international festivals are still going and hopefully as the economy picks up there may be more. There are a few smaller festivals and sometimes the odd new one pops up for a one-off event.

ARE THERE ANY YOUNG STARS MAKING AN IMPRESSION ON THE BRITISH KITING SCENE?

In the north of England we do have a few promising young kitefliers who make and fly single-, two,- and four-line kites. I’m not sure what is happening in other parts of the country.

HOW DO WE “OLD GUYS” RECRUIT YOUNG PEOPLE TO THE INTERNATIONAL KITE FLYING MOVEMENT?

That’s a difficult one – kite workshops, talks, visiting schools, kite exhibitions in museums and art galleries, kite festivals, and spectator participation for youngsters. Press, radio, and TV programs.

ARE YOU INVOLVED IN SOCIAL MEDIA TO PROMOTE KITING OR YOUR COLLECTION?

Yes, I built my own website (www.kiteman.co.uk) about 16 years ago to promote and show the fascinating world of kites. Sadly I have never had the time to update it, but over the years it has had millions of visitors and I still get many enquiries from it. The pages visited most often are those on kite history and my oriental kite collection.

I have recently photographed my complete Japanese collection, which will be available to view on Flickr in the near future. More of my collection to follow when time permits.

WHAT IS IT ABOUT KITES THAT HAS KEPT YOUR ATTENTION FOR SO MANY YEARS?

From those early days, kites have become a big part of our lives. Over the years we have participated at kite festivals in many exotic places. Jeanette and I married at an American Kitefliers Association Convention in Hawaii in 1989, and throughout our travels we have met many wonderful people, some of whom have become very good friends. We are lucky to have had so many magical experiences which have left us with unforgettable memories. ◆

INTERVIEW WITH BEN RUHE

Scott Skinner

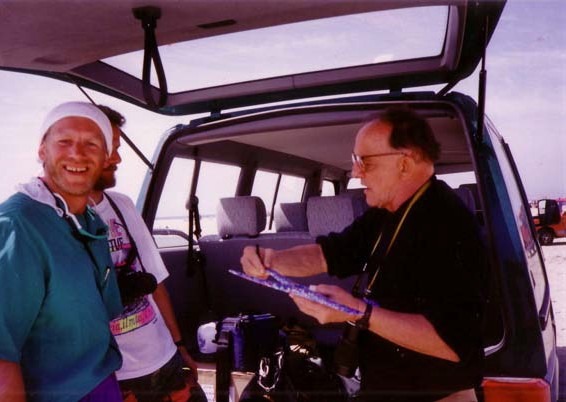

Ali Fujino. “We were in Germany doing a story for Drachen in 2008. We saw some students throwing boomerang, went over, and they said, “It’s Ben Ruhe!” and an autograph session started.” – Ali Fujino

INTRODUCTION BY ALI FUJINO

Ben was there for Drachen in the early years as the professional writer to research and document the world of kiting. As a world-class traveler, there was no place that Ben wouldn’t go to find a story, documenting the history and culture of kites. (Ben reports that he has visited exactly 84 countries!) It is his journalistic talents that have given the kiting world professional documentation in both written and photographic imagery.

He covered Asia, Europe, and Central and North America. Drachen could not give an exact number of interviews he conducted for us, but it is in the hundreds. His photo archive is in the thousands.

INTERVIEW BY SCOTT SKINNER

This article started with a simple premise; ask ten questions of Ben Ruhe for his memories about his work with the Drachen Foundation over the last 20 years.

As many of you know, however, a conversation with Ben often leads to places you had no intention of going, so what follows are “notes” from an hour on the phone with Ben. There may indeed be ten questions in there somewhere, but I think you’ll be happy to hear these thoughts and memories from Ben Ruhe.

Ben grew up in the country – a large property with lots of land and a swimming pool, a rarity in the days of the American Depression. Ben was the ninth child, and the 7th son. The family was highly educated with many of the children getting advanced degrees.

The first child in the family was a girl – a Depression child. She taught dance and married her piano player. He was a Colonel in the Air Force in WWII and in fact was heir to the Mack Truck family. He drove the company into the ground and was forced out of the business.

His eldest brother was a naval doctor in World War II. A second brother went to the Naval Academy and retired a Captain. Ben’s brother Joe was a veterinarian, and he flew the Hump in Burma – “had a very rough war.” Joe moved to Texas and bought a square mile of land!

Another brother was a musical genius, who died at age 21 of cancer. Another brother died in infancy. Brother Ed was marked by genius, turned down a scholarship to Princeton and went to Swarthmore.

Sister Judith was born as child #8, and Ben figured she is the reason he is around: the family had to have a seventh son. Judith felt disadvantaged as a female in a family of so many boys, but she still went to an Ivy League school and finished in just three years.

“That leaves me,” says Ben. Ben went to a variety of schools. At Columbia Law School, he roomed with an anthropology major. Ben found that all of his roommate’s friends were marvelous and all of his own were “dreadful,” so he figured law was the wrong profession for him.

He had worked earlier at The Allentown Morning Call, a medium-sized newspaper in the eastern Pennsylvania town. Ben’s father was editor for over 50 years. He lived through his sons and didn’t need to travel because he knew so many people from so many places – both from his own school days and from his sons’ travels.

After The Morning Call, Ben went to The Washington Star, a newspaper that had the highest advertising revenues of any paper at that time. But he saw it start to die as television changed peoples’ habits of finding news. Ben chose to “wander around” Washington, DC and write about what he wanted to.

Ben met S. Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian in 1968 and saw the conflicts between Paul Mellon of the National Gallery and Ripley of the Smithsonian. Ripley hired Ben for the Public Affairs office, but Ben quickly started to spend more time at the Smithsonian’s National Collection of Fine Arts, something closer to his heart.

Ben became Public Affairs Director at the National Portrait Gallery, a place with old- fashioned rules set by Congress, and then managed to switch to the National Collection of Fine Arts, run by Dr. Joshua Taylor, a long-time professor from the University of Chicago. Enter Ali Fujino, who arrived as an intern and soon was interviewing for a job.

Ben made friends with the director of the National Gallery, Carter Brown, who was coming in as a new Director, and Ben was asked to become his Public Relations Director. He was about to start when the job offer was rescinded because Ben was seen by Mellon as a “Ripley man.”

So, getting a bit bored with the National Collection, Ben moved to the National Endowment Council for the Arts, an organization led by the very best in the arts. The NEA was then led by Nancy Hanks, who simply told everyone what to do. Nelson Rockefeller was an admirer, so Nancy had no lack of political clout.

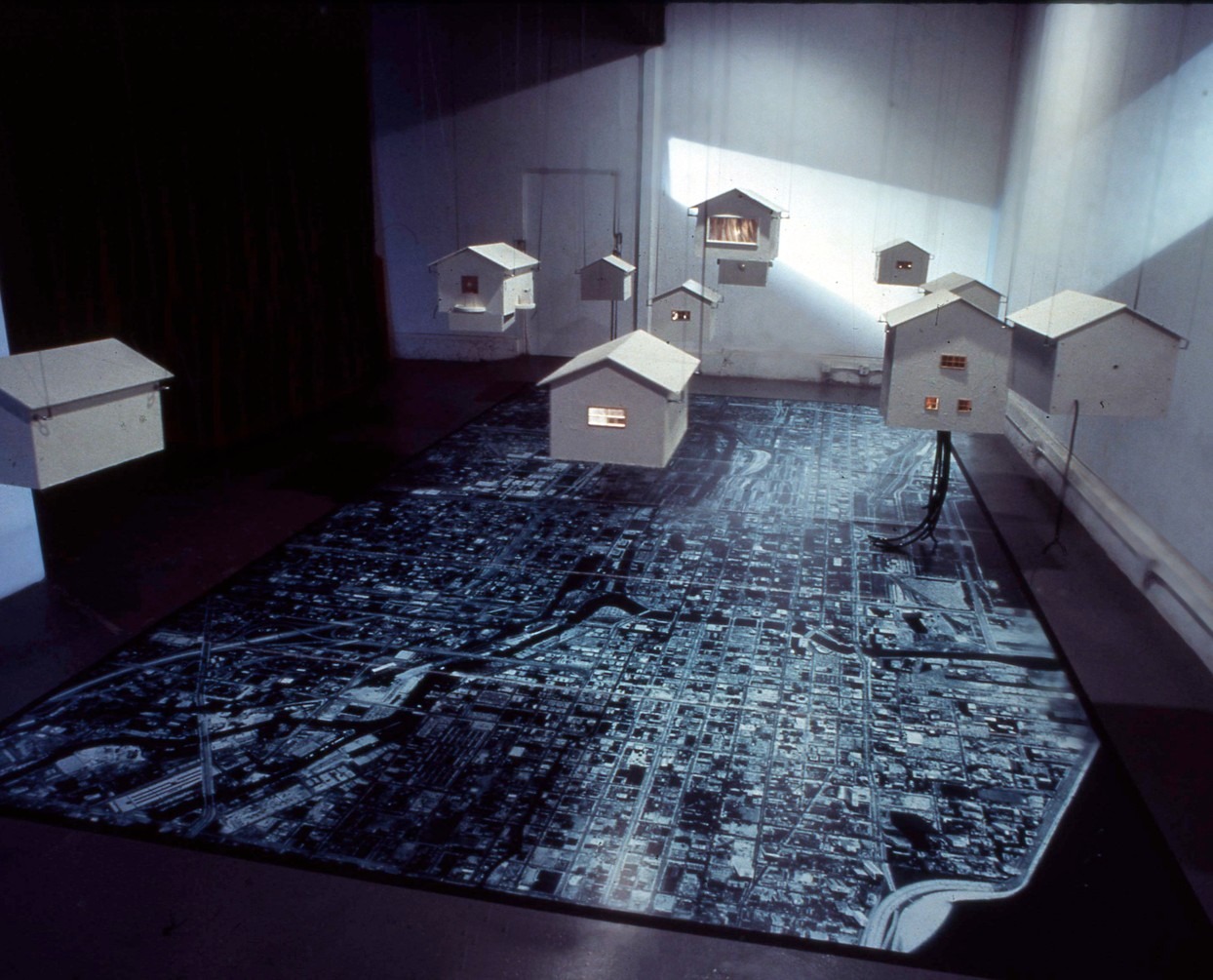

John Flynn. Ben Ruhe, winter 2015.

An avid traveler, Ben had traveled prior to his professional Smithsonian career. He discovered Australia, became enamored with boomerangs, and when he returned to D.C. suggested that perhaps a way to use the Mall would be to have a boomerang “Throw In.” The event mirrored a kite festival and was immediately successful. It quickly became a major competition dubbed “the Nationals,” and that took it out of the realm of what the Smithsonian did.

In 1981, Ben and Ali organized the Australian Boomerang Tour for three competitive matches and several demonstrations. The Americans won, probably through organization more than ability. Ben gathered an extensive collection of boomerangs and wrote extensively about the sport. Two years later, the Aussies came to the U.S. and won to save face. The sport took off right after this and Ben became “Guru Ben” in the Boomerang world.

Ben was familiar with kites through his friendship with Dr. Paul Garber, the leading kite expert at the National Air and Space Museum. But it was only after being introduced to the Drachen Foundation that Ben became truly interested in kites, and through Ali’s posting as director, he joined the staff as the chronicler of kite subjects.

With Ali Fujino, Ben wrote the first book of stunt kites, hysterically titled The Stunt Kite Book, even before his relationship with Drachen (he says quite seriously, “I had forgotten about that,”) and his growing interest in kites led to work with the Foundation. He authored and edited the Drachen newsletter, then moved to develop the tone and format for the Kite Journal.

On the articles he’s written for the Kite Journal and Discourse, he is most impressed with Jackie Matisse, “a splendid woman.” Also the kites of Curt Asker, especially his wonderful minimal sculptures that cast engaging shadows on background walls, and Istvan Bodoczky of Hungary as well, with his weird, asymmetric flying objects. The events of Betty Street and bill lockhart (the Junction Kite Retreats) were always interesting and inspiring as well as the wonderful people in Asia, where there is a higher reverence for kites.

“I’m not up on current developments,” says Ben.

Ben now resides in the serene coastal New England city of Gloucester, Massachusetts. In his late 80s, he is an avid reader and continues to edit Discourse for the Drachen Foundation. ◆

LINKS

Jackie Matisse Monnier www.drachen.org/bio/jackie-matisse-monnier

Curt Asker www.drachen.org/bio/curt-asker

Istvan Bodoczky www.drachen.org/bio/istvan-bodoczky

Betty Street www.drachen.org/bio/betty-street

bill lockhart www.drachen.org/bio/bill-lockhart

INTERVIEW WITH MELANIE WALKER

Ali Fujino

All photos provided by Melanie Walker.

A beautiful kite created by Colorado artist Melanie Walker.

YOU MAKE YOUR RESIDENCE IN BOULDER, COLORADO. HOW DID YOU GET THERE, AND WHAT’S A DAY LIKE IN BOULDER?

I moved to Boulder in 1992 when I was hired in a tenure track position in the photography area of the art department at the University of Colorado at Boulder. I had been teaching for about 18 years at that point at a number of universities around the U.S. but could never find a place to stay. I wanted to be in the west and it worked out.

A typical day in Boulder is usually jam- packed with scheduled boring stuff and counter-balanced with lots of curiosity. I have always been pretty inclined toward art and science so from cooking in the kitchen to working in the darkroom to making a kite, science and art are usually at the core of what happens in a day.

Right now I am in the process of trying to grow food from scraps. Kind of like exploring reincarnation in a funny way, if that makes any sense. So far there has not been a harvest but a lot of interesting pictures and lots of lettuce seeds. We have tried fennel, celery, lettuce, turnips, radishes, and all sorts of stuff that would generally go into the compost.

WHAT WAS YOUR CREATIVE CHILDHOOD LIKE?

I was brought up in an art family so I had nothing but encouragement for my artistic endeavors. I usually made stuff alongside my father, Todd Walker (www.toddwalkerartist.com), who was my primary role model and mentor. He was self-taught so I had this model of if you wanted to do something, just go do some research and then think with your hands by making whatever it was you were curious about. I recall vaguely when I saw someone embroider I went home and started sewing thread into paper. My parents encouraged that sort of inquisitiveness.

My mother, Betty, was an amazing seamstress. She designed clothes for people, especially my sister and myself, and would make special items for my dad’s advertising photo shoots. She had a passion for sewing and unfortunately lived in that cultural era where she was not able to develop it as “her” art, as the world of creativity was often a “male’s” domain. It was her passion and talent that I brought forth into my work. Most of my career in art has been concentrated on merging photographs with sewing.

WHO ARE YOUR HEROES?

My dad. Annette Messager. Anais Nin. Emily Dickinson (who I share a birthday with). Rebecca Solnit. I don’t know, there are so many.

IS THERE SOMETHING THAT AN ARTIST SHARED WITH YOU THAT YOU HAVE CARRIED WITH YOU IN LIFE?

That rules are made to be broken, and Never Stop Working.

WHAT WAS YOUR FAVORITE BOOK AS A CHILD?

I think it was The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster. I loved that there were countries called Digitopolis and Dictionopolis. And the Island of Conclusions which you could only access by jumping. I loved the puns and the plays on words.

WHAT RULES DO YOU LIVE BY?

Do the best you can, and the best you can be is perfectly flawed. And try to leave places better than you found them.

Melanie’s artichoke and cloud kites. “Do the best you can,” she advises, “and the best you can be is perfectly flawed.”

Melanie’s artichoke and cloud kites. “Do the best you can,” she advises, “and the best you can be is perfectly flawed.”

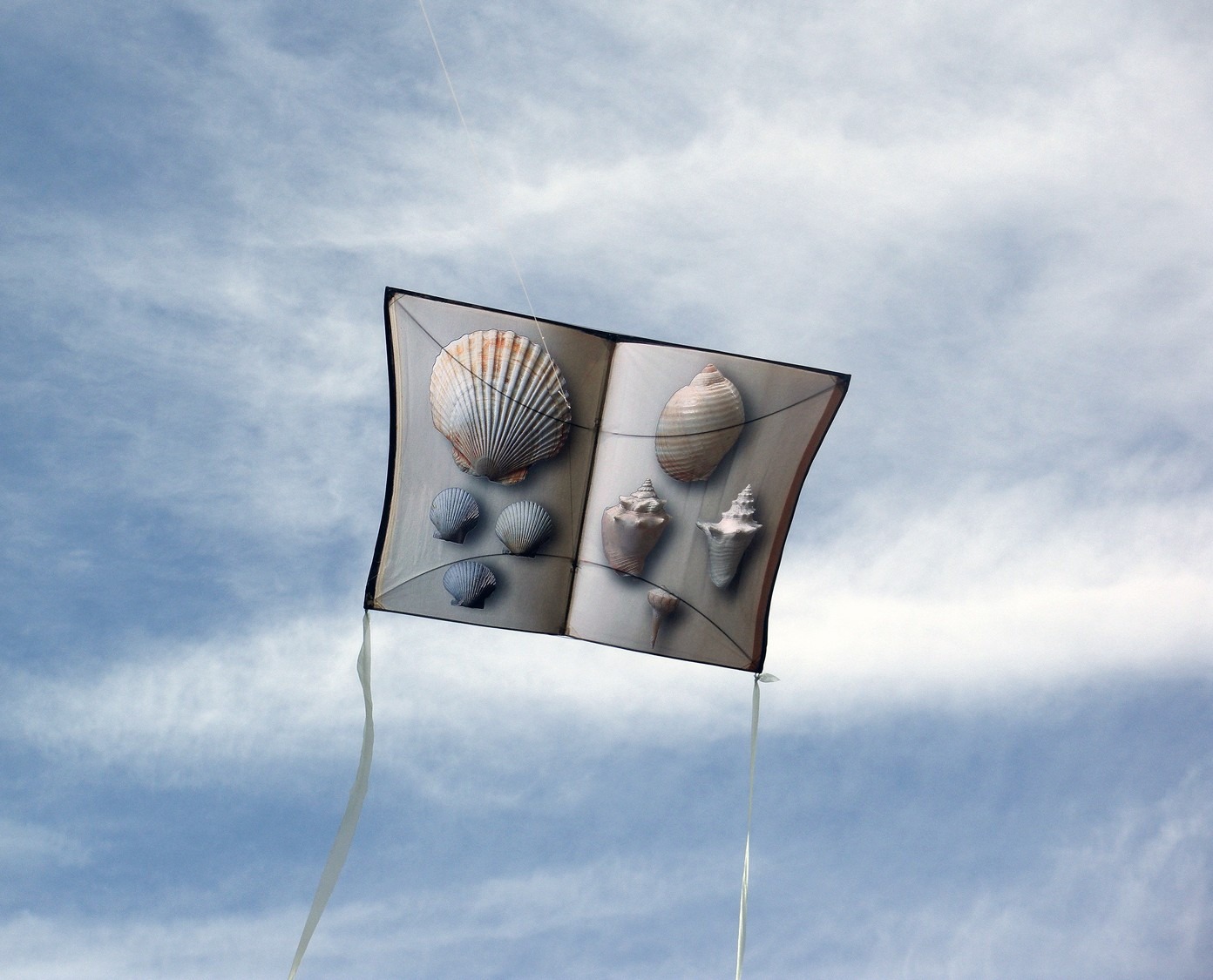

A flying installation of Melanie’s Househead Chronicle kites. “I love making the visions I see in my head and turning them into something out in the world. I love being able to see and feel the wind. Making ideas that can literally fly.”

WHY PHOTOGRAPHY?

I love alchemy. The fact that light can be recorded onto silver or two iron salts can become light sensitive. That a moment in time can be isolated and saved for reconsideration. I also love light.

WHY TEACHING?

I never wanted to give up on having access to all those tools available at the university. I love sharing and trying to get people excited about ways to tell stories, to show their world views, artistic activism.

WHAT IS YOUR FASCINATION WITH KITING?

I love making the visions I see in my head and turning them into something out in the world. I love being able to see and feel the wind. Making ideas that can literally fly.

WHAT WAS YOUR INTRO INTO KITING?

My first introduction to kiting was when I was a child and made box kites with my father. There was actually a Chevy advertisement that my father did back in the late ‘50s, in which I am standing on a hill with a collie watching a boy fly one of the kites my father and I made together. Many years later, my installations included suspended elements like hanging house viewing boxes and other components. When kitemaker George Peters and I met, I was pulled back to kitemaking.

DETAIL YOUR WORK IN MAJOR ART INSTALLATIONS THROUGHOUT THE U.S.

I have been exhibiting my work all over the country since the 1970s and I have work housed in many major art collections around the U.S. including the Center for Creative Photography, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, San Francisco Museum of

Modern Art, Princeton Art Museum, and many others. Together with George Peters we have completed over 90 collaborative public art projects both nationally and internationally.

WHO WAS A MENTOR IN YOUR ART JOURNEYS?

I think I have always been in creative dialog with my father. After he passed, it took me a while to figure out how to continue my visual conversations with him but I think that is starting to happen. He never stopped growing and exploring. I have so much respect for that. And that he walked away from a successful freelance career to pursue his research and teach others about the medium he loved.

WHAT ARE YOU WORKING ON NOW?

Oh, too many things as usual. I am not very disciplined and neither is George so I struggle with being constantly distracted, but the two things I am most excited about that I am working on are a graphic novel that involves a fictional family I have made work about off and on for over 30 years (!!!) and some new kites that involve making cyanotypes on a strong kozo paper. Cyanotype is a sun printing process that uses two iron salts that become light sensitive when mixed. They produce a beautiful blue color.

I am also doing some photographic work using decayed or destroyed negatives from my father’s archive. It involves work he did for hire around the time I was born. On some of them, the decay is extraordinary.

OF YOUR WORK, WAS THERE SOMETHING THAT WAS PARTICULARLY YOUR FAVORITE?

The Househead Chronicle, an ongoing body of work that examines and questions notions of home, homelessness, overpopulation, tradition, and family. Food, water, and shelter have long been considered basic human needs. Using the image of a house and the conceptual framework of home as metaphor, I seek to offer pictorial access to the longing for connection. The substitution of a house for a head implies a reality without being specific. It allows fabrication of a world and a narrative that occurs only in the photograph. Delving into the fantastic and the banal, the work addresses fictional metaphors for experience and emotion. Within this work I seek to create a theater where the ridiculous, the poignant, and the unexpected can be acted out through imaginary and whimsical associations that portray life on the lyrical edge of sense and non-sense.

An installation of the Househead Chronicle, an ongoing body of work that examines and questions notions of home, homelessness, overpopulation, tradition, and family.

An installation of the Househead Chronicle, an ongoing body of work that examines and questions notions of home, homelessness, overpopulation, tradition, and family.

“Using the image of a house and the conceptual framework of home as metaphor, I seek to offer pictorial access to the. longing for connection.”

Photographs of artist Melanie Walker’s mom and dad. “I was brought up in an art family so I had nothing but encouragement for my artistic endeavors.”

The series consists of two complementary forms: a suite of photographs and a range of installation components including shadows, kites, puppets, quilts, and images printed on sheer silk.

Throughout this body of work I have chosen to work with approaches that might be considered childish or playful. There is a rich political history in puppetry and kites have a way of drawing people in. I am interested in the tension that can exist when serious issues are brought forward in a manner that is disarming.

This approach relates directly to my first memory which involved eye surgeries associated with my birth defect. I was born legally blind in one eye and had eye surgeries at age three. I woke up alone after the surgery strapped in a bed with an eye patch over one eye to see a chimpanzee wearing a band leader’s uniform riding down the hospital hallway on a tricycle. This memory has been integral to my approach to making work.

WHAT IS YOUR EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND?

I went to undergraduate school at San Francisco State University for my BA and Florida State University for my MFA. I have been very fortunate to have continually held a teaching position since I graduated in 1975. ◆

THE SURUBÍ: A CREATIVE CONTEXT

Maria Elena García Autino

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. The Arch of Eddys, the first BaToCo group project.

“Thinking is the recognition of my ideas from the response of others.” – Alexander Kluge

What does a happy child on top of a mountain at the Argentinian Patagonia have in common with a group of youngsters living in poor conditions but enjoying a beautiful experience at the delta of the Rio de la Plata River in Buenos Aires? And with many other children all over Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, China, and Italy? Or with a grandfather who inhabits the joyful space of a gathering with his grandson?

All of them in some way or another participate in a creative public context of innovation and enjoyment rooted in the experience of a group of people. And I would like to describe this daring, meaningful experience of creation, encounter, and communication developed by artists, hobbyists, and enthusiasts of BaToCo (”Barriletes a Todo Costa” or “Kites at All Costs”), a group that was originally created by friends sharing a common hobby and is steadily enriched with new people, new ideas, new techniques.

I aim to emphasize the importance of a “context of participation” that transcends the activity of a human group and advances on the public sphere, enhancing it. I find the experience of Ba To Co illustrative of contemporary philosopher Alexander Kluge’s concept of “public sphere.”

Collective construction of large kites is not a BaToCo original or exclusive experience. It has been attempted and carried out by many others, in diverse parts of the world and at different times throughout history. The magnificent kite festival at Sumpango, Guatemala, with many teams working on the colorful kites, or the Bali Kite Festival, a seasonal religious festival, are good examples.

It should be noted that these experiences far transcend the mere creation of a beautiful object, but are essentially gatherings, a spontaneous association that emerges and expands between people who keep very special ties with each other. This collective experience is much richer than any individual or personal intention and generates an activity that transforms the context. It is the labor itself that establishes bonds that are not only interpersonal or limited to the here and now.

Each group kite is not only a piece put together with the participation of members of BaToCo and community but also represents the individual construction of multiple parts of a whole, creating a space for collective fun, where casual viewers passing by get involved to their surprise and curiosity.

All throughout the world, kites are usually built individually, though often collective experiences are had at festivals, tournaments, and competitions. In some cases, the kite construction itself is a cooperative effort that brings people together around a traditional event, acquiring social significance as an expression of protest, safeguarding ancestral cultural values on a manifestation of shared concern.

BaToCo has developed several group projects, whose progress can be appreciated on their website: www.BaToCo.org.

They probably originally arose from a playful experience among a small group of friends who met almost by chance a Sunday some years ago by the coast near the river. The encounter was casual and disorganized, with no other purpose than the fun and excitement of sharing those kites, surely crafted in traditional models to start with. They met almost exclusively to play together, with no purpose or reason other than to enjoy a beautiful object and a friendly gathering.

Victor Derka, one of the first BaToCo members, says: “There is no reliable record of the year BaToCo started as a group. In the years 1996 to 1998, builders had already been flying their first models on the coast of Vicente Lopez district, near the river. What characterized the group from the beginning was the free decision to enjoy the river, the get-together, and the first models that were, perhaps, rokakus. In 1998, the acronym BaToCo emerged.”

Almost unwittingly, they were creating a “public space” for participation, with huge prospects. In fact, that space, that invaluable encounter and communication, continues to grow today, incorporating new people, new ways to create and build, new experiences that expand participation.

In his essay “What Is Orientation in Thinking?”, as mentioned by Alexander Kluge, Immanuel Kant writes, “…how much and how correctly would we think if we did not communicate with others to whom we communicate our thoughts, and who communicate theirs with us!”

There are many and varied collective actions of social and community impact that in one way or another share the spirit of the batoqueros (BaToCo members) and are closely linked to it. Members never neglect to help even the most inexperienced build kites. They guide interested people personally or through worldwide forums.

Collective action generates other actions that expand the public space. This experience reminds me of the minkas or mingas, an ancient Latin American tradition. The minka or minga is a “collective work done for the community,” a pre-Columbian tradition of voluntary community work currently in use in several Latin American countries. This spirit is present, though not explicit, in the collective actions of the BaToCo group.

Perhaps the most important part of the experience of design and construction is what happens in the periphery of this center of intense creativity. Through its members, all outstanding builders, the experience expands to working groups in schools, hospitals, and community centers across the country. It generates new creative contexts and other public spaces of participation, which in turn also spread out. It generates links with the visual arts, literature, science, and with new magical universes never imagined before.

Therein lies the strength and the extraordinary power of collective epicenters, constituting significant differences between “being alone” and “not being alone.” As Alexander Kluge says, “Working, living, and loving in isolation as a hermit does not involve a civilizing opportunity.”

We are facing a situation of contemporary global crisis. Times of crisis discover potentials and generate collective action. This has been happening almost inadvertently in many groups in Argentina. BaToCo is one of them.

It is impossible not to wonder what has brought together the members of this unique group over all these years. It is the instinctive trust that, from the beginning, consolidated confidence in the skill, knowledge, and technique of each other. This confidence has been strengthened over the years, leading every collective proposal to success. They are artists when they perform their individual creations, and even more artists when bonded on a collective action.

Collective creation, though it leads to the construction of a playful object, is much more than mere entertainment. Entertainment is befogging. Creation opens a window to new horizons. Those big kites are see-through objects that do not end in themselves but open up unexpected possibilities.

In the shared BaToCo spirit, building a beautiful object together implies the collective construction of joy, maybe the best construction that a human group can accomplish.

Annually, members of BaToCo propose a kite construction project that will result in the joint work of the group.

THE ARCH OF EDDYS

This was the first group construction work achieved by members of BaToCo. The arch is 140 meters long and it frames all the encounters, welcoming artists and spectators to join BaToCo flights.

This project did not attempt to create an original design for each kite. A conventional Eddy model was chosen, but t he participation of every one of the group members gave a personal “touch” to each kite. It represents individuality when all its members gather to fly it.

This work participated in various kite festivals: the Festival of Rosario, the International Festival of Bogota, and the Buenos Aires Wind Festival each year.

GREAT SOUTHERN DRAGON

For the Festival of Rosario in 2003, BaToCo members decided to create a yearly new group construction project.

The idea to build this great flying giant was an attempt to reinforce the cohesion of the group and individual participation in a collective construction enjoyed by everyone. The result is a beautiful and huge flying machine that now crosses our sky. It has a majestic flight, and no one is indifferent to its presence in the sky.

PULPERÍA

Pulpería was a group BaToCo workshop that aimed to construct dozens of inflatable octopus kites, following Colombian kite builder Alejandro Uribe’s original pattern. (Pulpería is an expression that refers to a large group of octopi and also to a traditional rural pub or grocery store where country people used to meet.)

The octopi are inflatable kites 11 meters long, built of polyethylene and bound with tape. They have no rigid component in their structure and therefore are held only by the air inside them.

The octopi were flown on the Paseo de la Costa, the favorite place in Buenos Aires for BaToCo members to fly their crafts. Neither the fog nor the cold could stop this project. It was anticipated with great eagerness – dozens of octopi flying with their tentacles writhing in the air!

Lucky spectators passing by were amazed at this “phenomenon.” This workshop made clear the strength of the group.

LA BANDEROLA (THE BIG FLAG)

In 2005, BaToCo began a group project that aimed to carry out a giant kite, “La Banderola” (The Big Flag).

The great achievement of the project was to bring together all its members on a shared activity demanding effort, enthusiasm, and creativity. This project was noteworthy because many sectors of the community were involved on the design of the panels which, when combined, formed a huge Argentinian flag. BaToCo members, individual artists, schools, hospitals, community institutions – all worked hard to make each section of this giant kite.

Each one of the participants worked in their specific field individually or with the group they chose. Each panel also brought about group work that was later integrated with the final result, creating a kind of working fractal pattern that opened new and interesting perspectives.

Some of the panel designs by Roberto Fontanarrosa and other Argentine artists were reproduced to give the Banderola a national touch, representing our country all over the world.

BICENTENNIAL ROSETTE

The 2011 group project involved the construction of a kite baptized by BaToCo members as “Bicentennial Rosette.” It has the characteristics of a foil with circular shape. The model stands for the national symbol escarapela (rosette), and it was selected for the Argentine Bicentennial celebration.

THE SURUBÍ: THE LATEST GROUP PROJECT

The idea arose several years ago to make a giant, inflatable kite recreating a distinctive Argentine animal. The group finally chose the surubí and created a kite about 20 meters long and 7.6 meters wide. The surubí is a South American catfish whose population has declined significantly since the last decades of the twentieth century due to overfishing and dam building.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Great Southern Dragon kite.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Great Southern Dragon kite.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Pulpería, dozens of octopus kites.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Pulpería, dozens of octopus kites.

The surubí form allows us to make an inflatable that flies alone or with minimal help from a pilot. It is very suitable because it has a wide mouth and the body is quite flat, which gives a good surface for it to rise with the wind.

Various decorative patterns were proposed and drawn. The first ones seemed colorful but also very complicated and time- consuming. So the project lay in a drawer for nearly two years. During this time the group completed the “Rosette” and implemented several more workshops.

In 2014, some members of BaToCo insisted on resuming the project and decided to simplify the design using diamonds of alternating colors ranging from yellow to blue and shaping the body accordingly. This design greatly facilitates the construction because the boxes are all the same, just the color changes on each. When everything was simplified, the scheme was completed by cutting more than 600 pieces of fabric!

After building a quick test on polyethylene fixed with tape (a technique learned from kite builder Alejandro Uribe) to ensure evidence of relatively good flying, the sequence was more or less the usual one on BaToCo group projects:

- Decide on a computer design model and surface decoration.

- Investigate the availability of materials.

- Set up measurements.

- Print/plot molds or patterns in real size.

- Print the general scheme.

- Assemble sequence/joining of parts.

- Select and draw parts over the fabrics.

- Number the pieces and coordinate the hard work of cutting them. Organize the delicate and laborious construction.

- Join the parts, place reinforcements, and laboriously attain the desired shape, a task distributed among participants in successive meetings.

- Assemble the parts: first the set of pieces that make up the top of the fish, then the bottom. Once completed, the joints are reinforced with internal threads.

- Assemble the bottom to the top. The giant begins to appear. Fins are attached.

- Build the network of internal threads that fit the flattened shape of the body.

- Reinforce all joints. Place mustaches.

- Place threads and flanges.

- Inflate the Surubí with a blower to see the overall shape and volume.

- Perform a flight test.

The big size is an additional difficulty. To have a computer complete design helps organize the job.

Another challenge is to coordinate tasks in each workshop with usually between 10 and 15 builders. It is necessary to properly distribute the activities, so that the participants do not get bored and everyone feels involved in working and progressing the sequence. Groups of 2/3/4 people are structured to carry out a specific activity: cutting the fabric, helping with everything, classifying and sewing the parts, taking note of what has been done according to scheme.

Of course, there are primary enforcement activities (cutting, measuring, sewing, joining, controlling, scoring) and support activities (sorting, coordinating the lunch or snack, drinking mate, a caffeine-rich infused drink, calculating adequacy of materials, cleaning, sorting). Spontaneous activities like jokes, discussions, some gossip, planning future purchases, sharing festival photos, and travel planning are included.

Note: The Surubí is in full construction. It will probably be finished in February and first flown in March 2016, after sewing the flaps, joining the whole body, testing it in flight, and adjusting everything.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s “La Banderola” (The Big Flag), top, and Bicentennial Rosette, bottom.

BaToCo Group. BaToCo’s latest project, the Surubí fish kite, just completed.

Photos and videos of the group projects, the construction processes, and the final results can be found on the BaToCo website at: www.BaToCo.org/barriletes/trabajo_grupal/

So far, says Pablo Macchiavello, one of the leaders of this task, “I think it’s one of the most industrious group works we have done; we all hope to see it flying. This wonderful kite is emerging from the love we all have in our group for the kites and BaToCo.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is essential to include a reference to the ideas of contemporary philosopher Alexander Kluge. I feel indebted. I admired them on Kluge films on German television and in his books and lectures. To apply his ideas means to develop his powerful concept of “public sphere” and confirm its accuracy.

The details of the construction process and information on group experiences were provided by Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka.

Each and every one of BaToCo’s followers have contributed directly or indirectly to this article. The ideas, enthusiasm, and love belongs to all members. Thanks to all of them. ◆

Be a researcher and share your information on

any of our articles! Finding additional

information on kiting subjects is how we learn

more. If the information is worthy of print, we

will send you an official Drachen Sherpa

Adventure Gear light weight jacket. These

exclusive outdoor clothing items are

not available for purchase and are reserved for

authors and special friends of Discourse.

Send your research and comments to:

discourse@drachen.org