Scott Skinner

From Discourse 4

Ali Fujino

Ali Fujino. Kites by Mexican artists installed at the exhibit in Puebla. See more artist kites on the Drachen Foundation website at http://www.drachen.org.

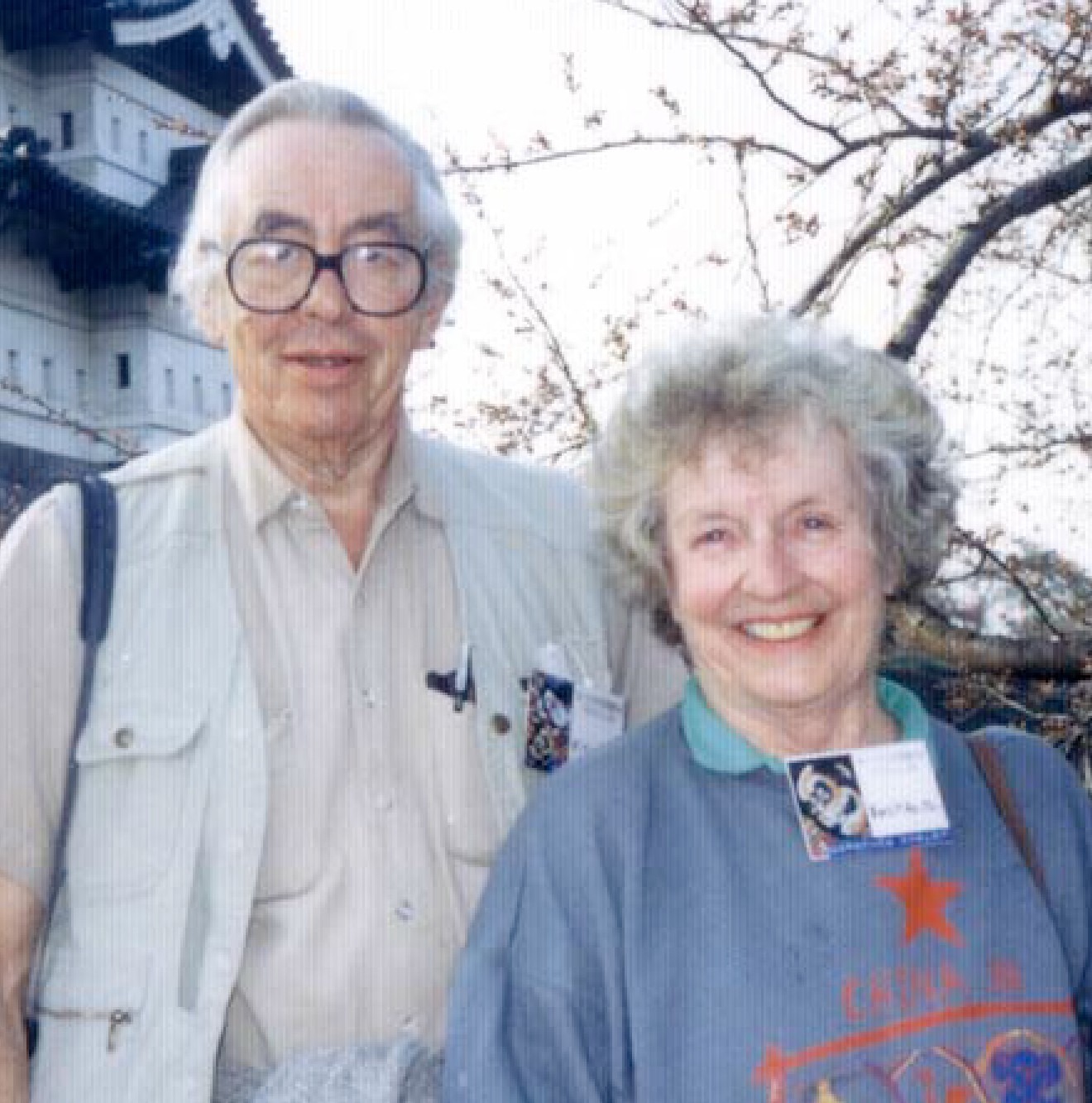

There is no doubt that influential Mexican artist Francisco Toledo is taken with kites! After last fall’s successful Toledo-inspired kite exhibit in Oaxaca, Mexico, for which the Drachen Foundation contributed over 50 art kites created by international kite makers, Toledo exerted his influence to exhibit the kites in Puebla, Mexico, a town two hours south of Mexico City.

Under the direction of Cesar Gordilla Aguilar, director of the Museo Erasto Cortes, over 300 kites were installed in Puebla’s Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art. This included two Drachen Foundation exhibits – Skyart, featuring the kites of Jose Sainz, Nobuhiko Yoshizumi, and myself, and The Artist and the Kitemaker by Greg Kono and Nancy Kiefer – as well as almost 200 kites from Oaxacan artists, and another 40 or 50 original Toledo kites. The site, a beautiful factory building from the early 1900s, was secured through Maestro Toledo’s urging that this space be made available for papalotes.

Drachen Foundation Administrator Ali Fujino and myself were invited by the government of Mexico to present kite workshops to Puebla artists and local “at risk” children. Pueblan artists, along with several artists from Argentina, contributed almost 150 additional kites to the exhibit. Many of these were finished in the workshop environment, while others were finished by Scott and the installation crew. The final installation included nearly 500 kites, the majority from Mexican artists.

The best may be to come. Mr. Aguilar is very excited about the possibility of an exhibit in 2010, featuring contemporary and Japanese woodblock prints and kites. This would be an ideal promotion for his museum, which features many of the finest Mexican prints from the early 20th Century.

THE WAY WE WERE

Scott Skinner

Another year has slipped away and memories of Y2K have become distant as the first decade of the 21st Century has almost passed. As we mark this moment, I want to take a look back at how we in the kite world have progressed to this exciting time: kite surfing a mainstream sport, resurgence of kite cultures throughout Southeast Asia, talk of “mega-kite-shows,” and real possibilities of significant kite power on land and water.

For most of us baby-boomers, we were influenced by an “old guard” of kite fliers, a group predominately from the WWII-era “greatest generation.” Can you imagine the raised eyebrows of their peers, when in the 1950s or 1960s these pioneers went out to fly kites? Here in the US, we remember Domina Jalbert, Francis Rogallo, Paul Garber, and other national figures, but there was a whole cadre of kite people who influenced me and my contemporaries. I’d like to offer some remembrances of people who had serious influence on my kite life, and ask that you take a moment to remember others who might have guided you.

DAVE CHECKLEY

My first international trip for the specific purpose of flying and seeing kites was with Dave in 1988. I had been involved with kites for over ten years by then, but had very little hands-on knowledge of ethnic kites. This trip to China changed everything. Dave led kite excursions to Japan and China for many years throughout the 1970s and 1980s and introduced countless people to the magic of Asia and its kite traditions. On that trip in 1988, among others, there was a “retired” actress, Gloria Stuart, who had traveled with Checkley to Japan in the mid-1970s. Gloria became famous again when she was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in “Titanic,” but she had carried on a love affair with kites since before WWII. Checkley was an active member in the fledgling early years of the AKA, virtually hosting the annual convention at his Seattle home in 1982. Sadly for the American kiting family, Dave passed in early 1989 while planning another trip to Japan.

Drachen Foundation. Photo of Margaret Gregor.

Drachen Foundation. Image of Dave and Dorothea Checkley.

Drachen Foundation. Image of Bill Lockhart and Betty Street.

Drachen Foundation. Image of Bill Lockhart.

MARGARET GREGOR

When I started flying kites in the mid-1970s, I hardly thought I’d ever have to make my own. There were just so many options available – Sky Zoo kites, Vertical Visuals, White Bird kites, the Nantucket Kiteman – why would I ever have to make a kite for myself?

That question was answered in 1984 when I attended my first AKA annual convention. Now my eyes were open to all the kite makers who were making their own creations. I met peers like Rick Kinnaird and his mythical BST, Doug Hagaman with his Giant Red Parafoil, and Scott Spencer, master of the snowflake. But I also met many of that greatest generation: Bob Ingraham, Tony Cyphert, Ed Grauel, and others. Somewhere along the way, I met a very retiring lady, Margaret Gregor, whose Kites for Everyone contained concise building information and flawless designs for a variety of kites. Margaret used input from many of the “old guard” kite makers like Len Conover and Ed Grauel, but also introduced us to the likes of Lee Toy and Steve Sutton, both whom would have a profound effect on American kiting. (Count the Sutton Flowforms at any major kite festival, or ask any kite artist who first pushed him toward art kites.) Margaret was a bridge from kiting’s older generation to today’s kite maker and workshop presenter. Her efficient uses of materials and foolproof designs are still the standard for elementary kite education.

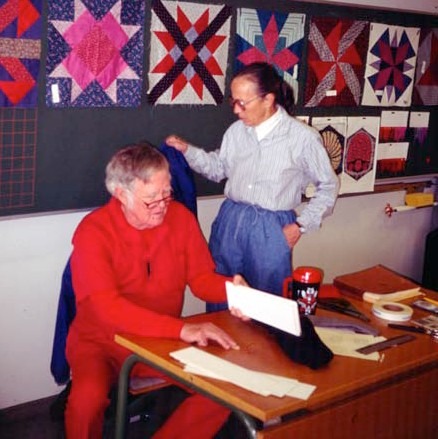

BETTY STREET AND BILL LOCKHART

It’s not fair, but I can never speak about just Betty, or just Bill; it’s always Bill and Betty, together, a team. With ten years of the Junction, Texas kite retreat, they raised the bar on kite education, inviting local and international artists to inspire and conspire to greatness. As art educators, their emphasis was upon creativity and originality, and they were (and still are) respected mentors for all of us who call them friend. Betty and Bill’s influence is still being felt. They were active travelers in the late 1970s and early 1980s and documented kite festivals with photographs and collected kites. Both have donated their kite collections, their slides and photographs, and their kite libraries to the Drachen Foundation so they can remain accessible to the active kite community. Finally, they also leave a wonderful legacy of their own beautiful kites, patchwork masterpieces that I was instantly drawn to back at my second AKA convention in 1985. Here was someone else using patchwork techniques and ideas that I had no idea existed! How lucky for me that they became such good friends and trusted advisors.

I hope these ramblings have inspired you to think about those who might have had a pivotal influence upon your “kite life.” The Drachen Foundation is interested in first- hand reminiscences for future publication in its Discourse: from the end of the line.

Email yours to discourse@drachen.org.

THE EARLY DAYS

Since the invention of the box kite by Lawrence Hargrave and the bowed kite by William Eddy, there has been only one man who created a major innovation in unmotorized flight. Of course every enthusiastic aviation specialist and kite-fanatic knows more people who were inventive: Otto Lilliënthal, Alexander Graham Bell, and Samuel F. Cody. From the perspective of innovation, though, the invention of Francis M. Rogallo was a real breakthrough.

As early as the 1940s, Rogallo started his experiments with the so-called flexible wing. That was the invention that led us to new kite designs by pioneers like Domina Jalbert and Peter Lynn. This was a systems innovation – in thinking and doing – because everybody assumed that a wing needed to be rigid with some kind of an aerodynamic profile. The real paradigm shift is in the innovative idea that the flexible wing, adjusting itself to the streaming of the air, might be a new perspective. Of course there were more ideas in history from flapping wings, balloons, and parachutes. The flapping wings need too much energy, balloons need additional heat, and parachutes have a wrong lift/drag ratio (L/D <1): they fall instead of flying. Rogallo worked on flying, the upward movement with a lift/drag ratio that gives more lift than drag (L/D >1).

Rogallo did not publish too much in media on his motives and work. There is one article of his published in Ford Times (43-3, 1951). He explains that his passion for kite flying originated from his early youth and always kept him fascinated. He became an engineer in aviation and started to doubt the quality of kite designs throughout history. He describes the quest for a better model:

“If we could combine the shape of the supersonic airplane with the unbreakable structure of the parachute we would have a very fine kite indeed.

But, for such a kite to fly, it must possess two kinds of stability – stability of shape and stability of position. If we could provide these, the rest would be easy.”– F.M. Rogallo, Ford Times, March 1951

The article, of course, ends with a perspective for the automobile: imagine having a flexible kite with a strong lift. You could get it out of the trunk of your car and you could fly away. Afterwards, you recover the kite, put it again in the trunk, and roll off in your car again.

That dream is not realized [1], but almost all his other dreams are, like this one: “Imagine the thrill of carrying a [kite-]glider in your knapsack to the top of a hill or mountain and then unfurling it and gliding down into the valley.” Then it was still a dream, now it is almost a daily routine for everyone who wants it so.

NASA Langley Research Center. On June 26, 1959, then Langley researcher Francis Rogallo examines the Rogallo wing in NASA’s 7×10 foot tunnel. Originally conceived as a means of bringing manned spacecraft to controlled, soft landings, Rogallo’s concept was avidly embraced by later generations of hang-gliding enthusiasts.

Francis Rogallo was born in Fresno, California on 27 January 1912. His mother was of French birth. His father was Polish and came as a young man to France. They went to the US because his father wanted to be a professional actor.

Francis Rogallo studied aeronautics at Stanford University for five years. After two years working for the Douglas Aircraft Company, he participated in a national competition to apply for a position at the Langley Aeronautical Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. He became employed by NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. He moved to Virginia, where he met his wife, Gertrude.

THE FIRST STAGE

In those years there was no professional interest at NACA (predecessor of NASA), where Mr. Rogallo worked, for the flexible wing. The war also forced different priorities. During the forties, Francis Rogallo decided to start his research at home. Though he worked as an aeronautical engineer at NASA, he didn’t get “room to move” for his practical experiments. At home he found a good partner. Gertrude Rogallo helped him with his tests and search for a good flexible kite. They made their first models of cloth that they had on hand, like some old kitchen curtains.

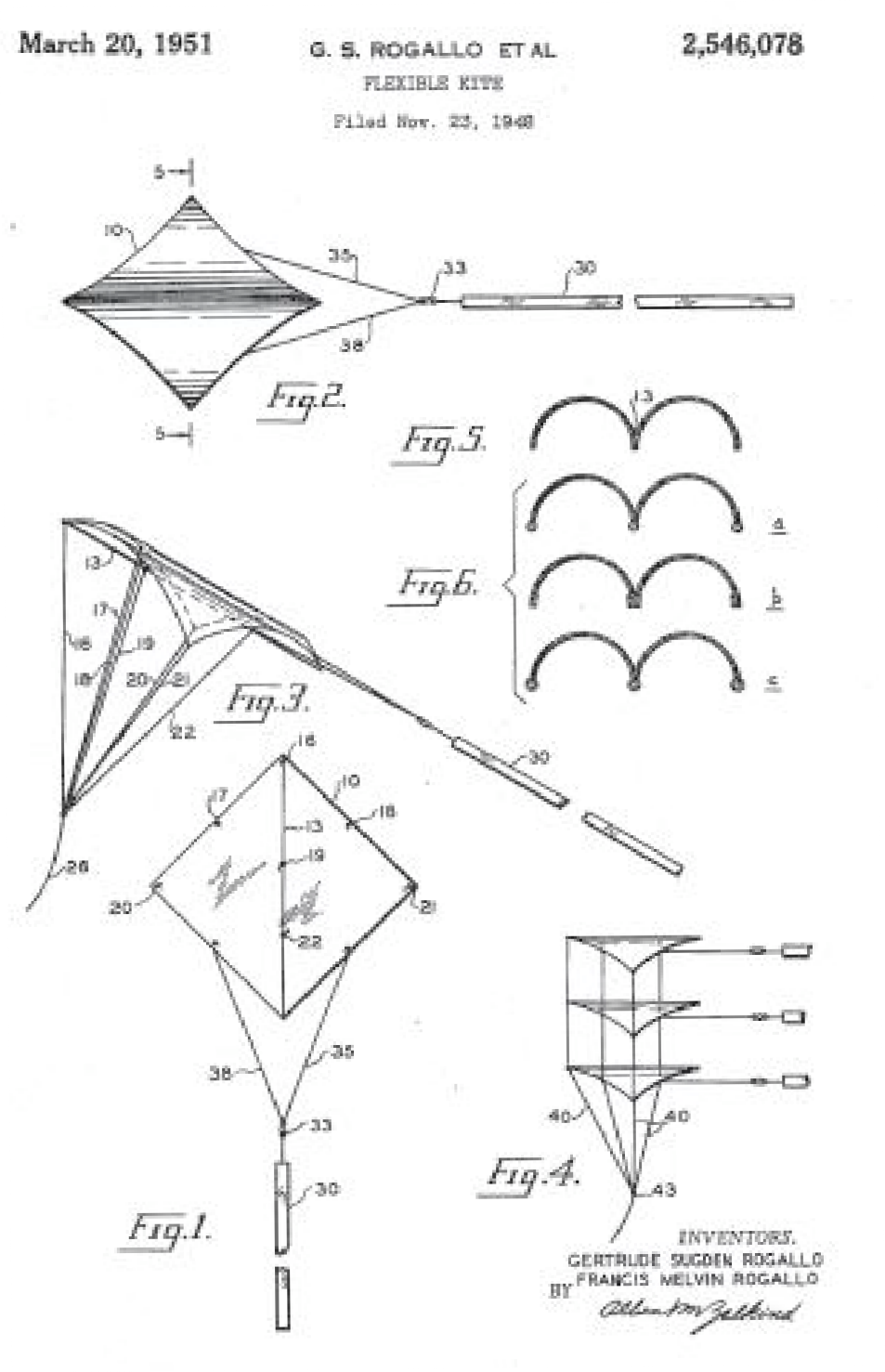

In the end, Rogallo claims to have had help from lots of friends and family. In 1948, Rogallo applied for a patent [2], registered to the name of Mrs. Gertrude Rogallo as a token of their love and cooperation on this project. In March 1951, the patent was granted to Gertrude and Francis Melvin Rogallo. In these years there was enthusiastic experimenting around the house. They made their own models of all kinds of cloth. They tried them as kites but also did drop tests like parachutes. The flexible wing was referred to as a kite, based on the three testing methods they used: in the homemade wind tunnel, inside or outside as a glider, and outside flying like a kite. In his house, Rogallo designed a wind tunnel by building a big fan in the kitchen door. He could manipulate the wind speeds. They did a lot of experiments with the bridling and the dimensions of the kite.

It took more than 13 years between the first tests and the first publications, before the government showed interest. The Rogallos never used the US patent for their personal gain. Their philosophy was that they had an income from the government through NACA/NASA and the patent was the least they could do for society. Also, the second patent [3] that they applied for and that was granted in 1956 is used in the same way. During the fifties, there was some commercial use: the Flexikite. The Flexikite was described as:

“Your FLEXIKITE, the world’s first completely flexible heavier-than-air craft, represents the first important advance in kite design in centuries. It is the invention of Francis M. Rogallo, eminent aeronautical scientist responsible for much of the research behind today’s high speed airplanes…. Because it is frameless, FLEXIKITE is more durable than old-style kites. And its ability to change its shape constantly to adjust for changes in the force of the wind makes it a responsive and interesting kite to fly.” – intro from the Rogallo Flexikite Manual

The Rogallos’ Flexible Kite patent

This kite was presented as a kite that could be flown as a single line kite or for dual-line flight. The manual states that the kite flier should be able to fly loops, dives, or figure eights. Its instructions can be used for any modern dual-line stunt kite. So it seems that Rogallo was also the inventor of the stunt kite, after Garber’s steerable kite. In the US, about 7,000 Flexikites were sold. Rogallo and the Flexikite Company used a very modern material that was just invented by Dupont: Mylar, the strongest plastic film ever at that time.

In later years, Mr. Rogallo once said that this wasn’t the smartest way to get serious attention for his invention: “Toys should copy the real thing and not the other way around,” Rogallo wrote in 1963.

THE SECOND STAGE

It was October 4, 1957 when the Russians successfully launched their first Sputnik into space. This was the start of an enormous transition in the United States. NACA became NASA in 1958. When Francis Rogallo met Wernher von Braun, they agreed to work further on Rogallo’s ideas. A special research group started, the “flexible wing section” at Langley Research Center. Rogallo worked there as aeronautical engineer.

All research from that moment on can be found at NASA. Rogallo’s kite research diminished as his focus moved to the concept of the flexible wing. The focus was on manned-flight, parachute-recovery for manned space flight, the parawing and hang glider. For kiters, it is necessary to be creative in reading the research. It is “circumstantial” evidence that you should be looking for. The scientific documents have prosaic titles such as “Low-speed wind tunnel investigation of a series of twin-keel all-flexible parawings,” but these are real treasures for the people who love flexible wings.

Cover of the original Flexikite manual.

The research group at Langley took their mission very seriously and performed tests with all kinds of models: parachutes, parawings, and further to paragliders with stiffened leading edges. All based on the concept of the first “flexible kite” from 1948/1951. Delta wings (hang gliders) are based on the Rogallo design with a stiffened leading edge. The history of the delta- shaped kites could have a different origin, as some authors state. It is difficult to say whether the delta-shape also included the idea of flexibility. [4]

At first, the Rogallo-wing (as the first flexible hang gliders were called) did not have the spreader, used as a steering-bar. Later hang gliding pioneers adjusted the Rogallo-wing, but amateurs and professionals still honor Francis Rogallo as the “father of individual flight.”

The delta-shape is also essential for flexible kites. The non-rigid parawings have two varieties: one-keel or two-keel. The first testing was done with one-keel parawings. Later, the keel was replaced by an extra rectangular piece of sail, so two keels can be found in those models.

The world renowned NPW5 is maybe the best kite based on NASA research of the sixties. Shroud lines are essential for its form that is shaped by the wind. The twin keel models have both keels because of the shroud lines that pull in the keel. The keels enable the controlled flight, and the middle piece of sail and nose give stability and power to this kite. Rogallo’s construction ideals were: easy to make and take for a display, easy to fold, well formed by the shroud lines, and simple to ride or hike with.

NASA did a lot of tests with these parawings. Film showed test flights with an Apollo model from a helicopter. The NASA test results became known in the industry, and that brought revolutionary new concepts for parachutes. Even nowadays a beautiful example of a Rogallo parawing is used as a safety parachute. [5]

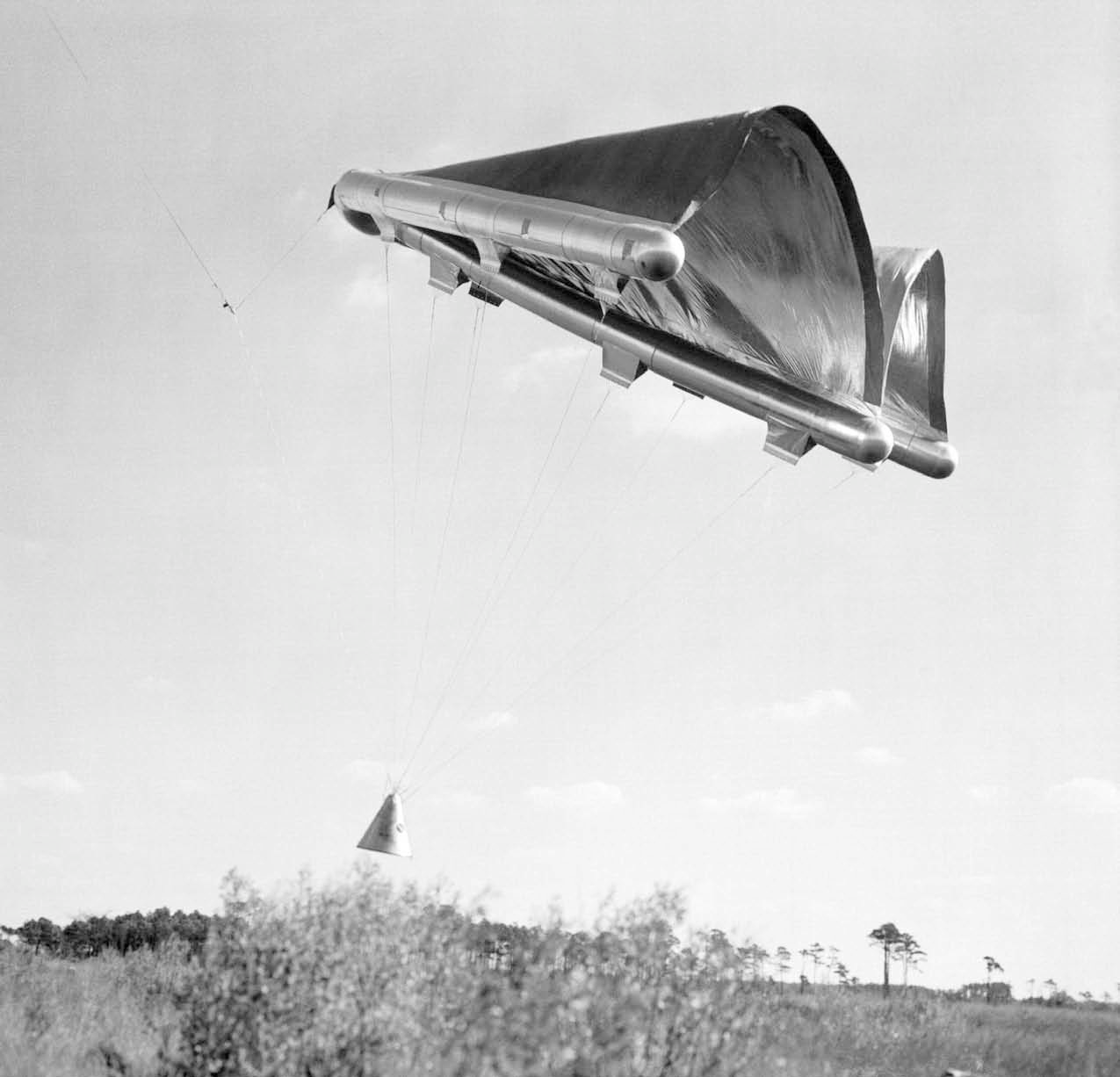

NASA Langley Research Center. Rogallo’s flexible wing, which was tested by NASA as a steerable parachute to retrieve Gemini space capsules and retrieve used rocket stages.

1961 JANUARY – SATURN FIRST STAGE RECOVERY SYSTEM STUDY

Marshall Space Flight Center awarded contracts to NAA and Ryan Aeronautical Corporation to investigate the feasibility of recovering the first stage (S-I) of the Saturn launch vehicle by using a Rogallo wing paraglider.

THE THIRD STAGE

During the sixties, NASA started to develop different models based on the flexible kite. NASA experimented with the material for the sail. Models made of aluminum and all kinds of plastic were tested in the wind tunnel. It was of significant influence on the lift-drag ratio (the upward power).

On 18 July 1963, a historical meeting took place in Washington. At that meeting the Rogallos gave all the rights on their patents to the American government. They did this with confidence that the government would continue their innovative work for civil and military purposes.

This was the start of two important developments: the flexible wing as the basis for hang gliders and the flexible landing parachute as the basis for parachuting and kiting.

The flexible wing got rigid leading edges and a rigid keel. This started the development of the delta wing as the basis for hang gliding. It was the Australian engineer John Dickinson who saw the potential of this wing for hang gliding. During the sixties and later, these original ideas brought a number of variations for hang gliding, ultra light flying, and parapenting.

In the wind tunnels of the NASA Langley Research Center, a series of experiments was performed during the sixties with single-keel parawings and later with double-keel parawings. The search was aimed at developing a new, steerable landing parachute for the Apollo and Gemini programs. Extensive test reports were published as “Technical Note” by NASA.

After all the tests, NASA saw the best potential in twin keel model number 5. With its double keel and the way it builds up lifting power, it had very solid performance indicators in comparison with classic parachutes. Its lift is 3 times as efficient. The literature does not reveal the reasons for NASA to neglect the new line of twin keel parachutes. My assumption is that the nose-collapse (that almost every NPW kite also does) might be the reason. NASA made their choice for safety and security; they kept using the classical parachutes. The movie-fragments of real tests show that the parawings were good landing devices. NASA tests on a 1:4 scale were performed with helicopter drops using two basic models: the one keel parawing and the two keel parawing number 5. These movie fragments can be found on internet. [6]

NASA TECHNICAL NOTES

NASA TN D-5936: Low speed wind-tunnel investigation of a series of twin-keel all-flexible parawings. R.L. Naeseth, 1970

NASA TN D-3940: Low speed wind-tunnel investigation of tension structure parawings. R.L. Naeseth & R.G. Fournier, 1967

NASA TN D-5199: Wind-tunnel investigation of the aerodynamic characteristics of a twin-keel parawing. G.M. Ware, 1969

NASA TN D-927: Free flight investigation of radio-controlled models with parawings. DonaldE. Heves, 1961

NASA TN D-538: A study of the feasibility of inflatable reentry gliders. Walter B. Olstad

NASA TN D-1614: Experimental investigation of the dynamic stability of a towed parawing glider model.

NASA TN D-443: Preliminary investigation of a paraglider.

NASA TN D-629: An exploratory study of a parawing as a high-lift device for aircraft.

NASA CR-1166: Investigation of methods for predicting the aerodynamic characteristics of two lobed parawings. M.R. Mendenhall, S.B. Spangler & J.N. Nielsen, 1977

NASA TECHNICAL NOTES ONLINE

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp

All the Technical Reports are now available as PDF or will be in the oncoming months. (NASA works very hard on PDF-ing their reports.) It is a lot easier to gain access to the knowledge that NASA developed during the sixties and seventies in their flexible wing research. Use words like: flexible wing, parawing, single keel, double keel, Rogallo, George Ware, or Robert Naeseth to get reports that might be of interest.

THE TESTS

NASA worked intensely on testing different Rogallo-wings. The models that were based on the complete flexible wings found their way to the parachute industry. It became the start of steerable parachutes. Already during the sixties, NASA developed different models, as did the Pioneer Parachute Company and Irvin Airchute Company. NASA started using dummies for the initial tests. When these tests gave good results and security, the real work was done by the US Army Parachute team. They performed the first real jumps. Within two weeks after NASA gave the design to the public domain, the first commercial designs were on the market. The parawings were a starting point for steerable parachutes.

Douwe Jan Joustra. The author’s own NASA parawings (NPWs), a bear and elephant. All have the beauty of simplicity, efficiency of power, and flow of the wind. Not only are they a backpacker’s dream, they are also the first step for many in building their own powerful steerable parawing. It is probably the kite model homemade most nowadays.

Douwe Jan Joustra. The author’s own NASA parawings (NPWs), a bear and elephant. All have the beauty of simplicity, efficiency of power, and flow of the wind. Not only are they a backpacker’s dream, they are also the first step for many in building their own powerful steerable parawing. It is probably the kite model homemade most nowadays.

For kiting, the twin keel NASA parawing number 5 (NPW5) was a breakthrough. There is a schism to be seen in its development. The primary line of development starts with the first flexible kite made by Rogallo. Together with the parallel development of delta kites, sled kites, and parawings, this led to the state of the art in kiting nowadays. It is the history of the flexible, steerable kite that became the success story of modern kiting: stunt kites, kite surfing, and so on. The second line in development started in the early nineties by the recovery of the NPW5 by kiters like Cees van Hengel in the Netherlands and Buck Childers in the US. They saw the research reports of NASA and guessed that flying the parawings as a kite could be possible. They were right. The NPW5 is easy to make, low budget, and efficient in material: a backpacker’s dream. In NASA Technical Note D-5936, the results of wind- tunnel tests are published for ten double- keel parawings. These models are all potentially working kites with different performances. At the moment, there are already different models on the market (NPW5 and 9), and plans are available also for numbers 9b and 10. Technical Note D-5936 gives detailed construction plans for all ten models.

NASA tested the models and number 5 seemed to be the most efficient model for their purposes: a reliable, steerable parawing with a good lift-drag-coefficient with the real ability of landing the Apollo or the Gemini. The reliability was good, so that was not the reason that NASA didn’t use these models as landing devices. In 2004, Mr. Rogallo suggested that there was no need to use them because the Navy was quite willing to recover the Apollos from the Pacific.

KITTY HAWK

The Rogallos never earned a penny on their patent. Francis Rogallo said in one of his interviews, “Since I was working for the people of the United States anyway, and my salary and now my pension comes from the government, I figured that everything I did should be given to the American public.” Francis Rogallo was a real kiter and also proud of taking flight himself on a Rogallo- wing. In older kite books, like those by Will Yolen, Rogallo is presented as a man who always had a kite in his luggage (easy whilst all his kites were flexible). The last decennia, the Rogallos live in Kitty Hawk. An excellent location for pioneers and innovators in manned flight!

- Though NASA did some tests on a “fleep” in the fifties (a flying jeep with a Rogallo-type parawing that was thrown out of an airplane), it did not become a success.

- US patent number 2.546.078 entitled “Flexible kite,” 1951.

- US patent number 2.751.172 entitled “Flexible kite,” 1956.

- The first Delta-shaped kite seems to be the US patent of R.F. Bach (number 2,463,135 in 1949).

- The Papillon; see http://www.vonblon.com for a short movie.

- http://www.dfrc.nasa.gov/Gallery/Movie/Parawing/HTML/ EM-0069-01.html