Katrien van Riet

From Discourse 13

When you combine a love for nineteenth-century literature with a love for kites, some interesting things happen. As I began researching nineteenth-century kite literature, I realized that there was preciously little material on the subject, even though nineteenth-century stories involving kites abounded. It soon became clear that the nineteenth-century kite had been largely glossed over in favour of the earlier electric kite hype (building on Franklin’s 1752 kite experiment), and the later developments in cellular kites starting roughly around the 1880s, which were a crucial part in the invention of the airplane. This period dating from the electric to the cellular kite is perhaps just seen as the long pause that separates one big invention from the next, but as I will show, the kite nevertheless underwent a fascinating development in nineteenth-century literature. In order to explore this statement, I am mainly interested in the moral aspect of the kite in children’s stories. I will look at a few poems and stories intended for a youthful audience, and describe how exactly the kite is a shaping presence in these texts.

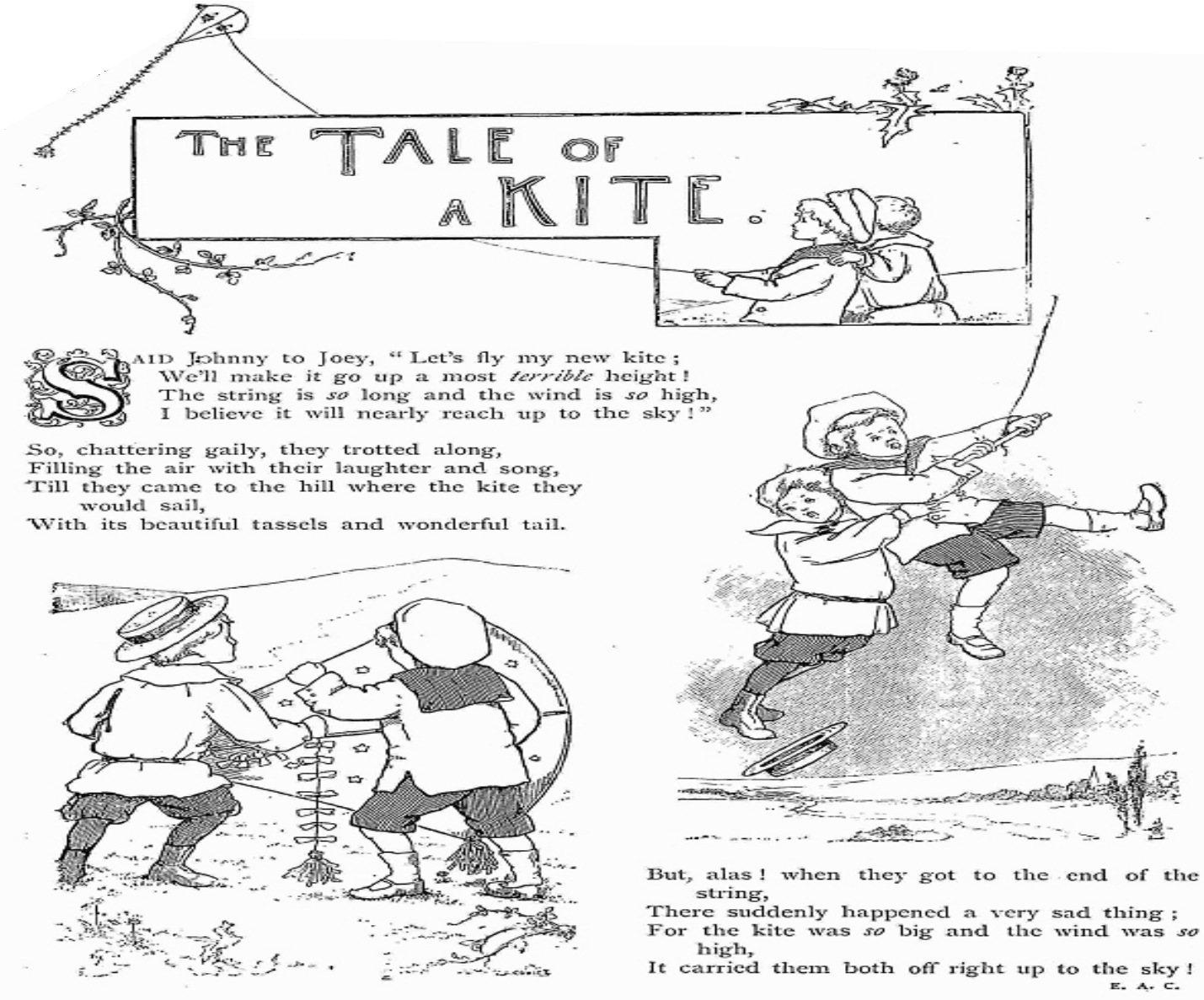

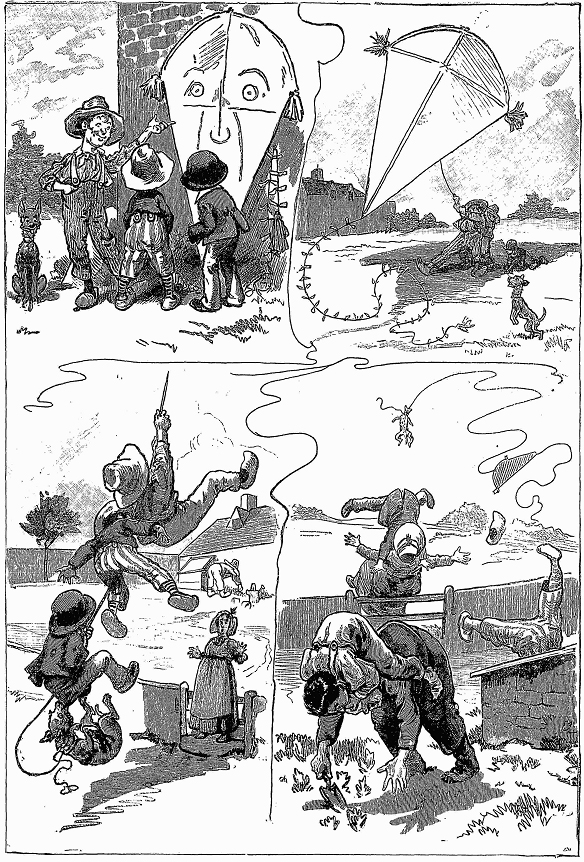

Victorian children’s magazines abound with pictures of kites broken free, or of children being carried off by an over-sized kite (figs. 2 and 3). This notion of freedom returns powerfully in the fundamental paradox of the flight of a kite: the kite pulls on the line, as if wanting to break free from its captivity, but it cannot stay up without being tethered. Of course, this duality did not escape writers who used the kite as a metaphor in their texts. As a result, this paradox was of ten used in moral imagery featuring the kite. In these texts, the kite represents a boy or girl who is tired of being told what to do, and the curtail- ing character of the string represents the child’s necessary obedience to its parents. They all contain the lesson that without restraint, a child will plunge (as a kite literally plunges) into bad behavior and will come to harm.

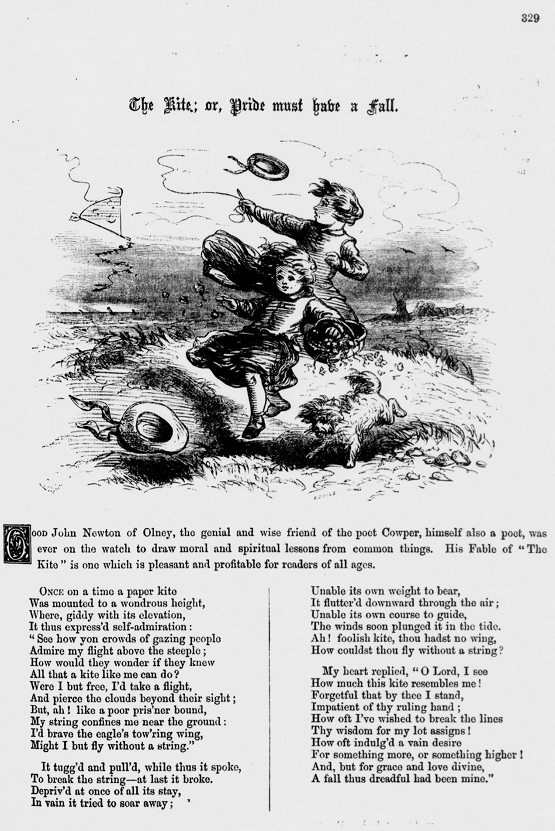

The comparison between kite and wayward child as it is depicted in “The Kite; or, Pride must have a fall” (fig. 1) was a very popular one. The poem begins with an image of pride. Almost like a real person, the kite yearns for appreciation and wants to display its talents to the crowd of people beneath, but it feels restrained by the string that tethers it. The kite is not only proud of the great height at which it is able to fly, it feels it can also do better on its own, without the restraint of earthly fetters (string) that literally hold it down. The kite then breaks the string to gain its freedom, but this turns out to be a bittersweet liberty. Restraint is necessary, the poem seems to say, even though the arrogant think they can do without it. Towards the end of the poem, physical restraint is transformed into a religious one: the string becomes a metaphor for the individual’s relationship with God, whose authority is portrayed as a good and much-needed part of life.

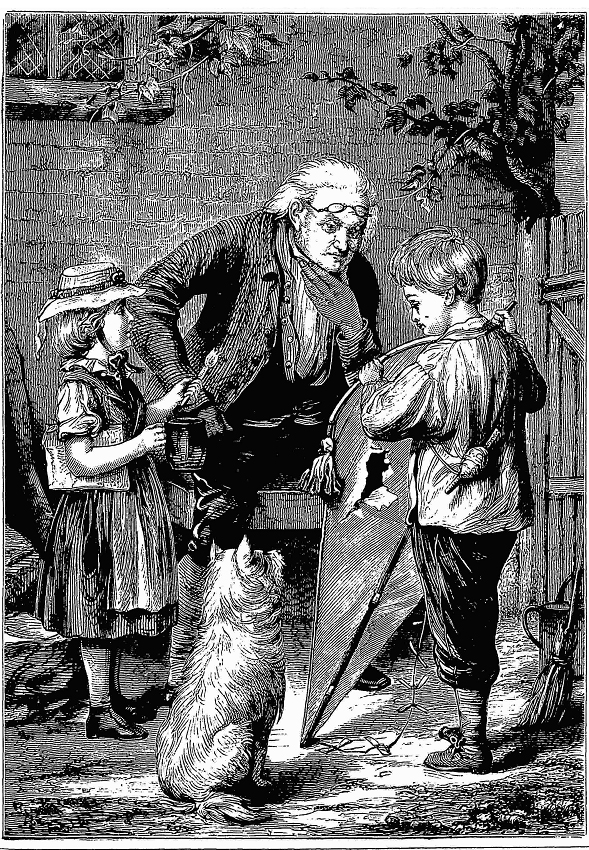

As it turns out, this poem brings across a moral message: do not be proud or conceited, as this will cost you dearly (in a physical as well as religious sense). Such messages return in many other children’s tales and rhymes as well. Figure 2 and 3 both portray children who bit off more than they could chew when they tried to fly an enormous kite. Such a warning of “self-conceit” is also present in “Charlie’s Kite.” Charlie did not follow his older cousin’s advice when flying his brand-new kite, and Charlie, being a novice to kite flying, soon had his kite caught on a tree that tore a large hole in its sail (fig. 4). Again, the message of the story is to avoid being conceited, which might cause children not to heed the advice of others more experienced (such as adults). The kite seems to come to harm so often that the image of the kite with a hole or tear in it becomes quite common, with writers coming up with new creative ways to harm their fictional kites. Figure 5 shows a picture from “Ups and Downs; Or, the Life of a Kite” in which the miserable life of a kite, including all its accidents, is portrayed. Of course, if the kite is harmed so of- ten, just the image of a damaged kite can come to imply the punishment of wayward behavior, which leads to the kite becoming a symbol in- stead of just a toy.

Figure 1: “The Kite; or, Pride must have a fall.”

Figure 2: “The Tale of a Kite”

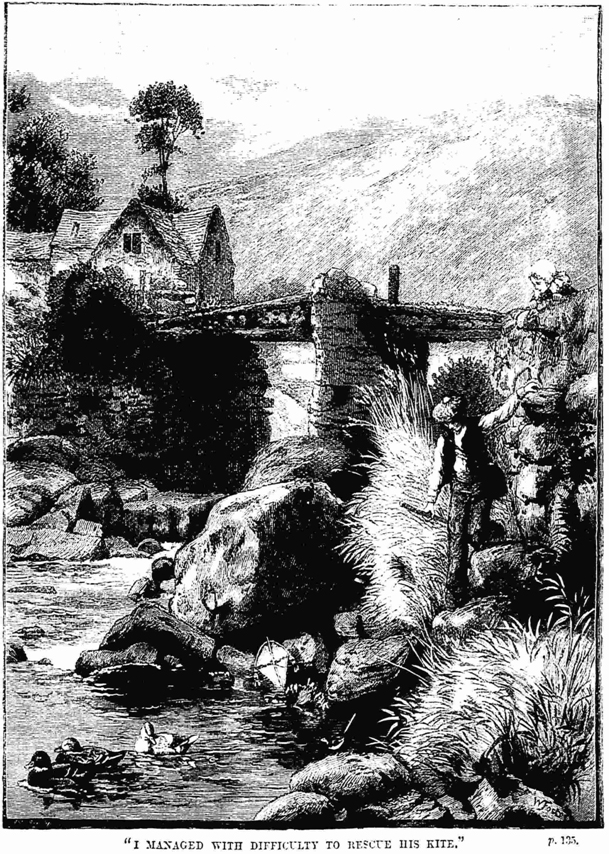

Although the kite doubtlessly appealed to writers who wanted to use the rebellious image of the kite as a warning, the kite was also used to represent hope and reward. These other stories highlight the importance of good conduct and honesty. “The Lost Kite”, for example, tells the story of three friends, one of which is jealous of the kitemaking abilities of the other. He tries to discredit his friend’s good reputation but is found out and forgiven. The image on the title page of the book shows the three friends having made up and standing around the kite, which, in a possible act of patriotism on the part of the artist, features a portrait of Queen Victoria. In “Found at Last, The Story of a Kite’s Tail,” a young lad is fishing when a small boy loses his kite. When a young girl asks him to run after the kite to see if it can be saved, the youth grumpily consents. He finds the kite lying half in the river and considers it lost, but after some persuasion by the girl, he fishes it out of the water (fig 7). When he examines the kite, he notices that one of the paper strips attached to the tail is part of a five-pound note, and as a reward for this find, he is given the full five pounds. Here the reward has literally fallen from the sky! In these texts, the kite seems to represent hope and reward instead of restraint or even punishment. The kite, it seems, could be used as a symbol in a wide selection of texts.

It is precisely this development of the kite into a symbol that is so interesting. As many kite fliers will know, it is hard to escape the prejudice that the kite is a child’s toy. That Benjamin Franklin was able to study the nature of lightning with it, or that it helped the Wright brothers develop their airplane seems to make little difference. A Victorian reading of the kite, on the other hand, does not overthrow the assumption that kites are for children. On the contrary, it suggests that this ‘childish’ nature of the kite helped establish the kite as a symbol of waywardness, recklessness, unpredictability, but hope and reward as well. In the texts discussed here, the kite says some- thing about Victorian culture: the importance it adhered to obedience, its focus on virtues (such as modesty instead of pride), and its praise of restraint. Especially this last quality is one that is seen in quite a different light today. Indeed, the thought that the kite can represent restraint instead of freedom might be surprising to some. When studying something as mundane and ordinary as the kite, such pre-formed twentieth-century notions are defeated, and new insights into the nineteenth-century are revealed. And you get to find pictures of kites that feature Queen Victoria.

Figure 3: “Boys Who Have Risen”

Figure 4: “Charlie’s Kite”

Figure 5: “The Kite and the Cow”

Figure 6: “The Lost Kite”

Figure 7: “Found at Last: The Story of a Kite’s Tale.”