Peter Boekelheide

From Discourse 4

This manuscript is the longest article submitted to Discourse to date. We present its first section here, and welcome you to read it in its entirety on the Drachen Foundation website at:

http://www.drachen.org/pdf/Survey%20of%20Chinese%20Kites.pdf

INTRODUCTION BY ALI FUJINO

One of the best aspects of my job at the Drachen Foundation is working with talented researchers who have found an area in kiting to investigate. Through the last 14 years, these individuals have come to us in many forms. Some have found one focus in kiting, some have worked at skills that enable them to study or research any given subject.

In the case of the latter, the work of Peter Boekelheide is a perfect example. A son of authors, he took a leave of absence in his junior year at Oberlin University to study in China. With the tools of Chinese language and appreciation for Chinese culture, he was armed to focus on something unique in China.

Why would the Drachen Foundation choose a non-kiter to research a contemporary kite movement in the “birthplace of kites?” For us, the answer was simple. Peter proposed his own style of study, a journalistic wandering to clarify fact and fiction about Chinese kites. Since he was not kiting royalty, the Chinese masters, factory workers, and hobbyists he approached had no reason to “put on a show.”

What impressed us about Peter is his tenacity to learn to speak the language. Communication is often the key to knowledge, and in the case of China, it is essential to peel back the layers of this complex onion. This helped Peter reveal the real China without being guided what to see. Take this opportunity to enter the world of contemporary Chinese kite making.

Peter Boekelheide. An example of Tianjin’s famous eagle kite.

Peter Boekelheide. Cold Tianjin.

IN SEARCH OF THE CHINESE KITE

Mr. Wei stands in his small store in a large shopping complex in the center of Tianjin. He wears a well-fitted but slightly fraying suit, and lounges against the counter as a young couple looks over the small collection of kites adorning the walls. The kites are of the typical varieties one would expect from from a Tianjin-style kite shop – sparrow kites, goldfish kites, but mostly the eagle kite, Tianjin’s specialty.

He is an older man, in his early sixties, and something about his demeanor is slightly intimidating. He holds himself with the air of one who knows, deep-down, that he is one-of-a-kind. And he arguably is. He is the fourth generation of the Wei family of kite makers, rock stars in the Chinese kiting world. For over one hundred years the Wei family has made kites, beginning in the late 1890s. Wei Yongtai was the personal kite maker for the final emperor of China, Puyi. During the Japanese occupation of Tianjin, Wei Yongtai’s grandson, Wei Yongchang, was famous for creating kite banners used to oppose the Japanese puppet government.

Now, Wei Guoqiu, the great-grandson of Wei Yongtai, owns “Wei’s Kites” in Tianjin. In addition to the running of his boutique, he participates in kite making competitions, teaches apprentices the art of kite making, and upholds his family’s tradition of artisan kite making.

Or, at least, sort of.

I came into the store late one Tuesday morning, happy for the respite from the bitter cold outside. It was January, and though Tianjin is not particularly far north, the immense grasslands of Mongolia to the northwest bring cold winds from Siberia, leading to a brutally cold winter. I had come to Tianjin for several reasons, all involving its history of kiting. When discussing kiting in northern China, Tianjin, with Beijing, Nantong, and Weifang, are said in the same breath as the major centers of kite development and production. And when discussing kiting in Tianjin, Wei is always the first name to be mentioned. Even in my most preliminary research into kiting in Northern China I’d come across Mr. Wei. His and his forebears’ works are discussed in modern kiting books, he is invited to kiting conventions around the country and the world, and his craftsmanship is considered to be of the highest caliber.

So I found myself in Tianjin, my thick jacket zipped to my chin, my eyes watery from the wind and cold, my face a bright red, standing face to face with this giant of Chinese kiting. As our eyes met, I suddenly felt very self-conscious. One has a certain picture in their minds of a master kite maker. I had always imagined a man crouched t ightly over his crowded workbench, his hair disheveled, splinters of bamboo and paint stuck to his clothes and hands, his fingers moving painstakingly slowly as they carve a piece of bamboo to the perfect angle. Mr. Wei couldn’t be further from this Gepetto-like image. Though slightly ragged at the edges, his suit fit him with an ease and comfort that smacked of tailoring. His shoes were shined to a bright black, his hair well combed. I was surprised to notice that his teeth were all intact, something one rarely sees in lower-class elderly Chinese people. Expecting a struggling artist, I instead found what appeared to be a moderately successful businessman.

And so my self-consciousness – I had to paint quite the picture. I was wrapped in an enormous black down jacket that I had just purchased, after some bit of haggling, for roughly five dollars. Despite the fact that the jacket was far too long at the torso, it somehow managed to be far too short at the arms, coming several inches above my wrists. Though I had purchased it only a few days before, threads had already begun to come undone on the arms and shoulders. My jeans were worn and dirty from the dust and grime that accumulates when one travels and I looked much more a traveling student than a wealthy connoisseur of art. And finally there was that factor that paints all interactions I’ve ever had – and ever will have – in China, that shaper of all communication, that most important aspect that wouldn’t change were I wearing Armani or a clown suit: I am a foreigner.

For all the talk of China’s new growth, its emergence as a world power, it is still utterly homogeneous. Outside of the major cities – Guangzhou, Beijing, and Shanghai – one is more likely to be kicked in the head by a mule than to come across a Westerner. But the West, and America in particular, still figures strongly in the imaginations of many Chinese. America represents many different things to Chinese people – from a bullying, head-strong world power to an inspiring example of economic success. Some Chinese will be delighted simply to speak to a Westerner, to be given the opportunity to learn about another country. Others will be openly hostile, finding any opportunity to bring up disagreement over Taiwan, Tibet, or the Iraq war. Still others will be hilariously under-informed, and think that America consists solely of California, New York City, and Washington DC, or that when at home I am under constant threat of terrorist attack.

But many Chinese, always practical, will see meeting a Westerner in a very specific light – as an opportunity, a chance to begin a business venture, to make a connection. As I would soon find out, this is as true in the kiting world as it is in the world of finance or trade.

As I stood in the entrance to his shop, I wondered how Mr. Wei would see me – as a thing of interest, or of opportunity? Would he be excited at the prospect of discussing kites with a foreigner? Would he lead me to his workshop, and show me the secret arts of kite making? Would we end the day, laughing gleefully as we flew our kites together in the cold January wind?

“Hi,” I said, brightly, a broad smile on my face. “You’re Mr. Wei?” He answered with a grunt. Undeterred, I continued on.

“My name is Bai Bing,” I began. (I often use my Chinese name when introducing myself. Shockingly, many Chinese find “Peter Boekelheide” difficult to remember.) “I represent a small non-profit company based in the United States that is dedicated to the cultural and historical preservation of kites and kiting. I’m here in China performing a small independent research project on kiting, and I was wondering if I could ask you some questions?”

I had begun this investigation only two weeks before, and was still slightly unsure as to how to introduce myself. So far my “profession” had been met with mixed responses – those heavily involved in kiting found it interesting, while those outside the kiting world would outright laugh. Given that the majority of modern Chinese kite makers are older – 50 and above – many have l ived through hardship most Americans can only imagine. The Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, the Tiananmen Massacre – all of these events were within living memory for these people. Most could recall times when they struggled to even survive, and the idea of a country so developed that people could spend money on the research of kites was understandably difficult to take in. Imagine going to west Baltimore and telling random people you were doing research on Scrabble, and would it be okay if you asked them a few questions. It was more than a bit laughable. But Mr. Wei did not laugh. If anything, he looked suspicious.

Peter Boekelheide. A certificate from the U.N. honoring Wei Yongchang. Spot the funny English.

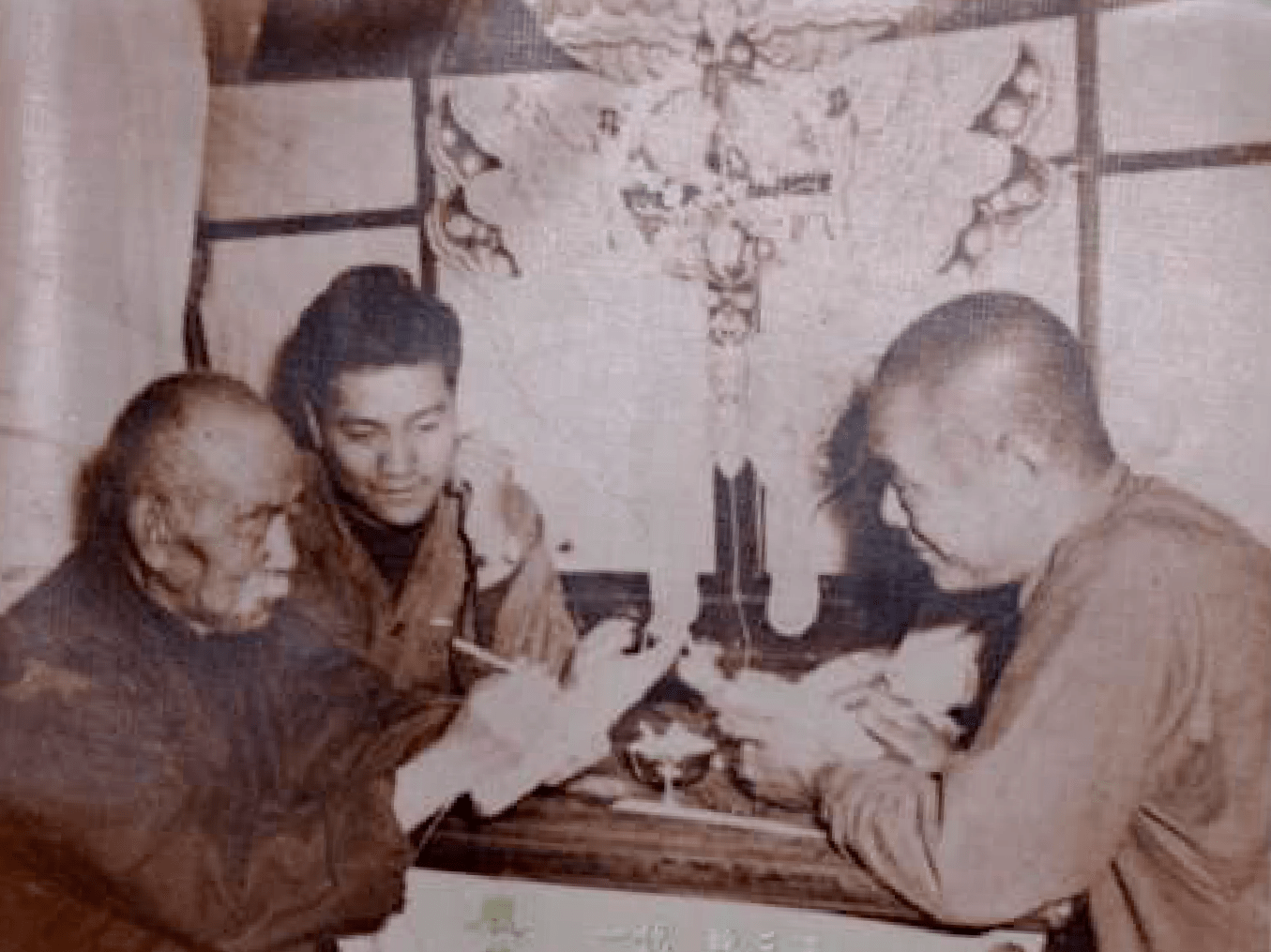

Peter Boekelheide. Three generations of Wei kite makers.

“You’re interested in purchasing kites?” he asked.

“No,” I said, slowly. I had been warned previously that Mr. Wei would not be what I was expecting, and this comment began to worry me. “The company I’m from is a non- profit. It’s interested in protecting the history of kites, but not interested in doing business. I’m basically acting as a journalist.”

“Ah,” Mr. Wei said. I could tell I was losing his attention quickly. “You’re doing research.”

“Yes,” I said. “And because I’ve read and heard so much about the Wei family, I was hoping I could speak with you at some point.”

Mr. Wei waved his hand at me, moving behind his counter. The young couple had left the store. “No time. I’m too busy.”

“Oh, yes, that’s okay,” I said. “I’m in town for several days, and I could come back later when you might have some time. Would that be alright? Later today, or even tomorrow or the day after?”

“No,” Mr. Wei said, not looking up. “I’m too busy.”

“It really wouldn’t take long,” I tried again. “Only half an hour or so.” He wasn’t paying attention and had moved behind the counter where he was fiddling with a pile of papers. Deciding that my original tack was not working, I tried a different approach, and began moving around the store, looking for a way to start a conversation. One of the pictures hanging from his wall was a picture I had seen before: three generations of the Wei family, sitting around a table, all making kites.

“This is you, right?” I asked. “I’ve seen this picture before. It’s you, your father, and your grandfather?” He grunted again, still ignoring me. I continued wandering around the shop, looking at the various models on display. One, a sparrow-style with twin heads, was of a type I recognized, and I pointed at it.

“This Beijing sparrow kite, with the husband and wife, it’s very nice,” I said.

“Yes, all of our kites are hand-made,” he said.

“You made all of these?”

“No, the factory did,” he said.

I looked at him, a little confused. “I’m sorry, the factory? These are made in a factory?”

“Yes,” he continued. “It’s outside of Tianjin. All of our kites are made there.” As he said it, another couple entered the shop.

“Where exactly?” I asked. Mr. Wei looked at me again, the same look of distrust on his face.

“I’m sorry, I don’t have time for this. I run a business, I don’t need to help researchers.”

That ended the conversation.

I would think back on this interaction many times in the course of my investigation because it represented in a nutshell what kite making in China is today. In the end, it is a business. Artisan kite makers in China are businessmen out to make a profit, and the Western idea of the traditional artisan kite maker simply does not exist here.

There are those who lament the “death of kiting” in China, as if kite making and kiting in general has shifted dramatically from the past due to years of upheaval and a recent embrace of capitalism. On the contrary, what I have come to believe is that, in fact, kite makers in China have always been businessmen, making a product for personal profit.

The man spending all day every day making kites, passing on the tradition for the sake of his art, dedicating himself to the beauty of kite making, has simply never existed, or at least not in that form. It has always been much as it is now: people out to make a living. In the past, this was done through the sale of kites to government officials and imperial courtiers. Now it is done through bulk sales to multinational corporations and independent sales to wealthy foreigners and locals.

Nor has there ever existed earnest academic study of the art of kite making – outside of a few dedicated hobbyists, kites are mostly regarded as a children’s toy, or an idle distraction. A society that so values practicality has little time for the study of something as impractical as kiting.

Is this to be lamented? I don’t see why. Kites still hold a special place in the culture of China and the lives of Chinese people. Kite makers may be more out to make a living than out to work on an art form they love, but that is not to say that their work lacks cultural, historical, or artistic merit. To think otherwise at best shows a naiveté regarding the economics of the situation, and at worst shows a sort of cultural condescension.

I came to China with little knowledge of kites, prepared to find armies of Geppettos working deep into the night to perfect their art, magically sustained by only the orgiastic joy they derived from kite making. I was in for a surprise.

“No!” the cab driver yelled at me as I lifted my bag. “It’s too big!” he said in Chinese.

“I know it’s big, but I think it’ll fit. Where else can I put the damn thing?” I said back in Chinese. He grinned.

“You speak Chinese,” he said, still smiling. “Okay, okay. Well, maybe we can fit it in here.” After some pushing and shoving, we’d jammed the enormous backpack into the rear of the taxi.

It was January 2006, and I had just landed at the airport in Beijing. It was my senior year of college, and I had spent my entire junior year abroad in China, studying the Chinese language intensively. I was returning after only 8 months away.

My junior year in Beijing had been in some ways the typical study abroad experience: we students drank too much, we traveled everywhere we could, and everyone slept with everyone else. But, because it was China, it was also anything but typical. Every day was both an adventure and a farce; tasks as simple as buying groceries, getting a haircut, or going out to dinner would turn into hours-long excursions filled with things none of us had seen before. Sometimes it was exciting or hilarious – we’d find ourselves shooting AK-47s, racing motorcycle cabs through crowded streets, or attempting to find the best way to politely decline Chinese friends’ offers to purchase us “massages.” At other times it was frightening and dangerous. One friend was forced into a car and beaten after dancing with the girlfriend of a high-level Chinese mafioso. Another was cheated for over a thousand dollars after blacking out at a bar and coming to in a karaoke club, surrounded by empty bottles and stuck holding the bill. A third crashed the motorcycle he’d rented and spent two days trying to find a way to get back the passport he’d used as collateral for the rental.

Peter Boekelheide. The interior of Three Stone’s Kites in Beijing.

Peter Boekelheide. A kite flier in one of Beijing’s many public squares.

My time in China had been the most fascinating, frustrating, hilarious, and affecting period in my life, and I was looking for any opportunity to go back. So, when I was told I could return to perform an investigation in modern Chinese kiting, I pounced at the chance. My investigation began that January, in 2006, when I traveled to Weifang, Tianjin, and Beijing. It continued two years later, when I visited Kaifeng, Nantong, and Weifang and spent considerable time in Beijing.

So it was that I found myself, bundled up against the bitter cold of January in Beijing, being yelled at by a cab driver. After we had stuffed my luggage in the rear of the cab, I got in, and we set off towards the city.

Beijing cab drivers, one quickly finds upon coming to Beijing, love to talk. They’ll talk about anything – politics, the weather, the traffic, their love lives, your love life, and everything in between. And most cab drivers in Beijing relish the opportunity to speak Chinese with a foreigner, the conversations going something along these lines:

“Um, where to?” the cab driver will say slowly, unsure if you understand Chinese.

“The Xindadu Hotel, over in Xicheng, on Chegongzhuang street,” I’ll respond.

“Oh wow!” the cab driver will exclaim. “Your Chinese is so good! That’s the best Chinese I’ve ever heard. That’s better than my Chinese.”

At first this makes you feel really great about your Chinese language ability, until you realize that every single Chinese person will say this to you, regardless of how little you’ve said or how terrible your accent is. You can say “hello” to some people and they’ll go on to tell you that you are destined to be China’s next Shakespeare.

This is especially hilarious, because Chinese is, well, extremely difficult to learn. As a result, I’ll have problems with every aspect of the language, from grammar, to pronunciation, to just forgetting how to say something. I’ll want to go to the library, but forget how to say the word “library.”

“I am to be going big building on the Beijing west side,” I will say, a pained look in my face, hoping beyond hope the cab driver won’t think I’m completely insane. “To the big building with the you-can-take- books. You know? You know what I mean?”

Oddly enough, it often works. “Oh, you mean the library?” the cab driver will ask. “The Western City Library?”

“Yes!” I’ll say, nodding vigorously. “The library. I want to go to the… library,” emphasizing it to make sure my pronunciation is correct. The cabbie will nod. “The library,” I’ll say again, “for the you-can take-books.”

Then the cabbie will tell me that I am a wordsmith of the highest caliber.

Though most of those problems went away as my fluency rose, the first week back after 8 months in the US was a bit of a struggle, as my skill-level had fallen from months of disuse. My first conversation with my cab driver on the way to my hostel, in which I explained to him why I was squinting so much, showed me I had some catching up to do.

“Well, I need eyeballs,” I told him solemnly. “Because my glasses are broken. Or, no, my eyeballs are broken, so I should be wearing glasses. But, on the airplane, a woman stepped on my eyeballs – I mean glasses. I have invisible eyeballs in my luggage, though, so it should be okay. You know? You know what I mean?”

See, in Chinese many words sound very similar, the only difference being the tone or inflection. The word for “glasses” sounds the same as the word for “eyeball,” but with different tones. And the word for “contact lenses” literally translates as “invisible glasses.” So “eyeball” is yanjing, “glasses” is yanjing, and “contact lenses” is yin yanjing. Thus my confusing story, though I’m certain the cabbie knew exactly what I meant.

The conversation ended quickly after that, so I watched the city, tracking the change. People always talk about China’s exploding economy, its meteoric rise, how nothing looks the same day to day. When you live there, the sight of rows and rows of buildings being knocked down or rebuilt becomes so everyday to you that you hardly notice the constant construction. It is not until you leave and return that you realize, wow, this place is completely insane.

I’d been gone only eight months. The run- down, ‘50s era, Communist-style apartment buildings on the drive in from the airport had been replaced with ultra-modern towers of gleaming metal and glass. Many of my favorite restaurants and bars had been relocated, expanded, or destroyed outright. The city is constantly in flux, its economy growing so quickly that it is unrecognizable one year to the next.

My hostel, though, and the buildings around it, remained mostly the same. It was only a few blocks from the dorm where I had lived my junior year, and I knew the area well. On the west side of the city, it is an area more removed from the enormous capital investments you see in the eastern and central areas, and it thus holds a sort of quirky third-world charm. Only ten minutes away by foot one can find the “bulk clothing market,” an outdoor/indoor market so large it occupies three twenty story buildings and the streets surrounding them. The buildings are a perfect example of the strange developed world/developing world dichotomy that is modern urban China. The buildings are brand new, built within the last decade, and from the outside they would not look out of place as an office building in any American city. But inside, instead of rows of offices with thick wooden doors or a garden maze of gray cubicles, one finds thousands of clothing stalls, none of which are more than fifty feet square.

The stalls sell everything, from shoes to luggage to every article of clothing one can imagine. Invariably in complete disarray, the shops have clothing strewn about the floor, and piles of new deliveries wrapped in burlap sacks. And the noise. The noise is incredible, cacophonous, overpowering. People yell out prices, men carrying huge loads of clothing to be delivered yell for you to move out of the way, women tending shops grab at your arms and yell at you to “looka, looka” or just “buy!”

This is part of what I enjoy about the area, the fact that one can still see China amidst all the gleam and shine of money and the West. But at this point I had only just begun my trip, and after four weeks of traveling alone through city after city on the never- ending search for the Chinese kite, I would find that I wanted little more than some Western gleam and shine.

Read the full article on the Drachen Foundation website at: http://www.drachen.org/pdf/Survey%20of%20Chinese%20Kites.pdf