TWO BROTHERS ATTEMPT 1000KM ALONG THE BEACHES OF BRAZIL

Harry and Charlie Thuillier

From Discourse 11

Harry Thuillier. Learning to zig zag downwind as the sun sets over the coast of Brazil.

Charlie Thuillier. Brothers Harry (left) and Charlie with their buggying equipment.

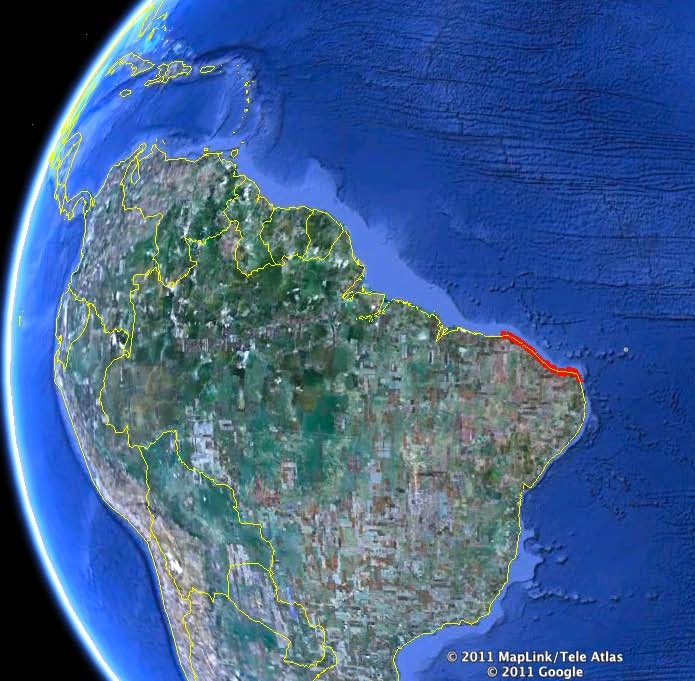

Harry and Charlie Thuillier are two brothers from the United Kingdom. This August they decided to kite buggy along the coastline of Brazil from Natal to Jericoacoara. They did it without vehicle support, without being able to speak Portuguese, and having only had one lesson in kite buggying. Harry takes up the story…

As we bolted together the buggies, strapped on our bags, and set up the kites on a windswept beach in Natal, Brazil, a few local kids and dogs stood in the doorways of shacks and watched curiously. Atlantic waves crashed against the sand, their roar muffling against the cliffs that rose from the beach behind chattering palm trees as we laid out kite lines and bars and put on our helmets. We knew the learning curve for what we were about to do would be steep but we were raring to go.

A few months ago, Charlie and I had a crazy idea. To go to Brazil and kite buggy 1000 kilometers [about 620 miles] along the Northeast coast from Natal to Jericoacoara. It’s one of the windiest places in the world, with hundreds of miles of beaches interspersed with dunes, mangrove swamps, rivers, and fishing villages. As far as we knew, no one had attempted to kite buggy this distance before without full vehicle support.

We asked Craig Hansen (member of the record breaking kite buggy team who crossed the Sahara and manufacturer of the PLK Outlaw buggy) what he thought our chances were. He had a few questions. “Have you kite buggied before?” No. “Has anyone buggied that stretch of coastline?”

No. “Will you be using vehicle support?” No. “Do you speak Portuguese?” No. He concluded: “I think you’re mad, but I don’t see why you can’t do it.”

I had butterflies in my stomach as the plane descended over the coastline of Brazil and into the start point of Natal, laden with the 150 kilograms [about 330 pounds] of gear we had managed to bring by pleading with the airline at the check in desk while wearing our Centrepoint charity t-shirts.

As our adventure began we realized that even for an experienced buggier much of the terrain was often awkward and offered little margin for error, let alone for two guys who had only had one lesson each. Although some of the beaches and dunes were a kiter’s paradise, deep streams that appeared out of nowhere, narrow beaches, palm trees, wind turbines, fishing boats, and sharp rocks meant it took 100% concentration. I made the first error just half a kilometer into the journey. At Genipabu, a village just north of Natal where the wind was cross shore and therefore directly behind us, I overtook my kite and caused it to drop out of the sky, before running over the lines and tangling them around my axle. With 999.5 kilometers to go, this was frustrating and the first of many lessons.

Despite the abuse, the Ozone depower foil kites took our incompetency in their stride. Two 4m Access XT kites became our workhorses. At higher wind speeds they still generated a lot of power but were stable to control. After a few hundred kilometers our confidence began to increase. We began using 7m and 9m Frenzy kites which were more dynamic than the Access XTs and had to be treated with more respect.

Using wind power alone was part of the ethos of this adventure, and we had already decided we didn’t want a vehicle to follow us – even if budget for it had been available. The idea was to use kite buggying to explore an unknown coastline under our own power without relying on the assistance of a 4×4.

This is a nice idea but it presented several challenges, and we had to navigate around impassable terrain on foot. Our progress was often dictated by the tides, and we had just a few hours in which to kite each day before high water would make it impossible to pass, with tires in the sea on one side and palm trees threatening to catch the kite on the other. Even at low tide it was a little nerve racking coming up to a headland and navigating a course under the cliffs, hoping the water was low enough to pass all the way through.

With unreliable maps, our almost non- existent grasp of Portuguese, and contradictory local opinion on the route, we ended up hauling the buggies further than we anticipated, walking as much as thirty miles a day on several occasions to avoid river deltas and mangrove swamps – the shoulder straps from BuggyBags.co.uk proved invaluable.

The terrain meant that our progress was slower than planned and the money that was meant to last until we reached Fortaleza was almost extinguished 300km (4-5 days buggying in good conditions) short of the city. With village banks not accepting foreign cards, our funds were running low despite our efforts to save by eating once a day and buying from stalls. We also saved by sleeping in our hammocks in basic pousadas, where you had to look where you were s t epping for the cockroaches and rat droppings! Despite this frugality, when we got to the town of Macau we made the hard choice to dismantle the buggies and try to reach one of the international banks in Fortaleza before our money ran out.

After a series of lifts by VW dune buggy, wooden raft, and bus (where we bribed the conductor to let us take our 150kg of luggage on board), we finally found ourselves in Fortaleza, the largest city in the state of Ceara. It was night time. With our last 50 reals we convinced a taxi driver to rope our buggies to the roof of his ancient Peugeot and drive to the city center, where to our relief we found a bank that would let us withdraw cash, enabling us to get back on track with the trip.

Whenever we slowed to walking pace around villages and towns, we were followed almost constantly. The people were incredibly friendly and always eager to help. In a fishing village called Aranau, curious children emerged in twos and threes and followed us for miles, chirping questions in Portuguese, kicking the tires, opening our bags, and jumping in the buggies. Perhaps this was because a foreigner was such a rare sight, or that people’s ideas about personal space are so different in Brazil to England, or that we were hauling each other along in odd vehicles adorned with bags and camelpaks that ironically looked like fuel tanks.

With no support vehicle, we carried all necessary spares, but the strong design of the Outlaw buggies (developed for the more extreme Mad Way South expedition in the Sahara) meant that no repairs were required. The Ultraseal tire sealant we had treated each big foot tire with no doubt saved us from punctures on occasions when we ran over cacti, broken glass, and sharp stones, although there was one close encounter. A wheel collision near the end of the trip in a remote spot east of Cruz damaged a valve, rapidly deflating the right tire on one of the buggies. This meant a tense stop, with two of us tentatively pushing the tubeless tire off the rim to fit a new valve and whooping with relief when it popped back on.

Harry Thuillier. The brothers hauled their buggies on several occasions to avoid river deltas and mangrove swamps. On this day, they walked miles, pulling the buggies with shoulder straps.

Harry Thuillier. Swimming a river too wide to kite across, contending with strong currents due to recent heavy rains inland.

Harry Thuillier. Untangling kite lines on the beach.

Harry Thuillier. Charlie buggies at sunset. Harry writes: “I had heard about the state of ‘flow’ from adventure kite surfer Louis Tapper – where the challenge and your competency meet and you find yourself fully absorbed and satisfied in an activity. At times I think we were both lucky enough to experience it.”

But any setbacks were worth it for the feeling of flying along, knowing the buggies could handle almost anything. When you’re traveling at speed, kite buggying feels like the best mode of transport in the world – salt spray rushes past you and the tires make a humming sound as they glide over sun- baked sand. The kites soar overhead, scattering wildlife like a bird of prey, and the look on people’s faces as you race past them under wind power alone is priceless.

As we started going faster and further, buggy control became more of an issue. Hitting large obstacles and bumps meant staying seated was easier said than done. Both of us had some epic “out of buggy experiences,” and our full- face helmets paid for themselves. Carrying all our supplies (and even a local passenger each one day!) there was a lot of inertia when starting and stopping. When the kite generated more power than our balance and legs could handle, we had several unintended flying sessions – often ending up 10 meters from our buggies, head first in a dune.

Another challenge was hidden streams. We would often find ourselves traveling at 30mph to suddenly see a river, twenty meters wide with a two foot drop-off into the water. Craig Hansen had told us the buggies could float with us in them, but with the 30kg extra gear we were carrying, we initially didn’t want to try it, preferring to pack down the kites and swim, pulling the buggies behind. But one day we tentatively steered down a river bank whilst flying the kites and found that the buggies did indeed float despite the extra weight! By the end of the trip we were taking a few seconds to power through rivers that might previously have taken an hour to cross.

The need to focus on negotiating the terrain in high winds meant kite control had to become second nature, or risk having too much or too little power. This came with practice as we progressed up the coast, and once we had gained in confidence we even challenged Louis Tapper (a Kiwi kite surfer who broke the record for the longest distance travelled without vehicle support in 2010) for a race downwind between Cumbuco and Icaraizinho. Although our straight line speed was slightly faster, Louis won by cutting across the bays, which we thought was cheating!

As we travelled the final kilometer of our trip, I remember thinking how lucky it was that we had had no major accidents. At that very moment I saw Charlie’s kite heading for a set of power lines.

We were on a bumpy coastal sand track which served as the only route into our destination, Jericoacoara. It made for some exciting buggying, especially as we were now sharing it with 4x4s heading into the town and had to keep right. Charlie was just ahead of me. With the late afternoon sun in his eyes, he had been focusing on an approaching blind corner and not on the sky. By the time I noticed the cables, obscured by the setting sun and the shadow of a hill and yelled out, the lines had hit.

A bright white flash, a high pitched hum of hot metal, and one of the cables broke, narrowly missing Charlie and hitting the ground. We both paused for half a second, in shock, as the fallen wire set light to a pile of donkey manure. After alerting the power company and walking the final couple of hundred meters into Jericoacoara, thankful that at least no one had been hurt, we realized we had made quite an unintended entrance. Candles illuminated dimly lit rooms. Ceiling fans hung still. The streets were black. This wasn’t the finale to the journey we had anticipated, but luckily the power came back a few hours later with a cheer from the locals, and we were able to reflect on the whole adventure.

It had been odd but exhilarating to wake up every morning and have little idea of what was around the next bay. Learning the sport at the same time as exploring new territory was mind blowing. All our senses were constantly occupied, scanning the ground ahead and looking out for each other as we crossed terrain that no one had ventured over in a kite buggy before. I had heard about the state of “flow” from adventure kite surfer Louis Tapper – where the challenge and your competency meet and you find yourself fully absorbed and satisfied in an activity. At times I think we were both lucky enough to experience it.

The frustrating thing was that we only started to become competent in the last week or so of the adventure. With more knowledge of the terrain, the sport, and the people along the route, we wanted to go back to the start to do it all again! But that’s what adventure is about – it’s all about the learning and the journey.

To watch onboard videos and leave your comments on the trip, go to www.kitebuggyadventure.com [no longer active]. The Thuillier brothers have been raising funds for Centrepoint, a charity which supports and houses homeless young people in the UK. You can donate here: www.justgiving.com/brazilkitebuggyadventure

THANKS TO:

Ozone Kites, PLK Outlaw Buggies New Zealand, OceanSource.net, Computer Solutions NZ, BuggyBags.co.uk, 2C Solar Light Caps, New Balance Shoes, Video VBOX GPS, Club Ventos, Serrote Breezes Jericoacoara, Ultraseal, SB Kites, and everyone who has donated to Centrepoint.

THE GEAR:

- Ozone Depower Kites 2x 4m Access XTs 7m, 9m, 11m, and 13m Frenzys

- PLK Outlaw Expedition Buggies with Racks

- Beach Racer Tires on steel rims

- Ultraseal tire sealant

- All bags from BuggyBags.co.uk

- New Balance All Terrain Shoes

- 2C Solar Light Caps