Ben Ruhe

From Discourse-2

Wolfgang Seitz. Recreating the flight 100 years ago that inaugurated an important water-borne weather station at Friedrichshafen, Lake Constance firemen use their fast emergency boat to tow an historic weather kite replica aloft. Scientific instruments aboard could record masses of useful data so that accurate weather predictions could be made. Kites were flown on a daily basis to altitudes of many thousand feet. Because of the tow, wind was no factor. The replica kite was made and flown by the international Historical Kite Symposium while holding its annual meeting in the city.

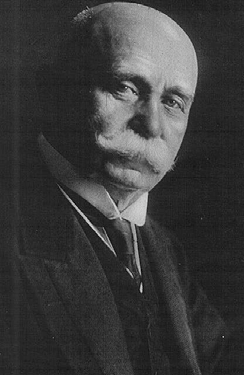

A busy Lake Constance ferry port in the south of Germany, Friedrichshafen is inextricably linked to the stately Zeppelins built and flown there for the last century. The link to inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin remains strong. Throughout the city, streets, schools, cafes, even a dress shop are named for him. A children’s slide near the sprawling waterfront Zeppelin Museum is shaped like an airship.

Because the huge, lighter than air flying machines required good weather predictions to be safely flown, a kite link with the Zeppelin evolved soon after the flight of the first Zeppelin in 1900. Professor Hugo Hergesell, of Strassbourg, a friend of Count Zeppelin, proposed that a weather station be set up in the area. Since Lake Constance sits in a bowl surrounded by mountains, the only feasible space was the 30-mile-long lake itself. Hergesell urged a fast boat for towing weather kites and both Count Zeppelin and the surrounding regional states, often at odds, but not this time, joined in financing the concept.

A steam-powered 18-knot speedster named the Gna (a Nordic nymph who lives in the water and then rises into the air) was built and the weather research commenced in 1908. As part of the celebration of the 100th anniversary of that event this year, Friedrichshafen mounted a major exhibition in the waterfront Zeppelin Museum. The institution also served as host to the international Historical Kite Symposium honoring the event. This group, mostly German but with a smattering of members from as far afield as New Zealand, showed off choice historical kite recreations on the waterfront in front of the museum and, as a main public event, flew a replica weather Boxkite from a speedy fire department boat out in the lake, just as had been done many years ago. The kite rose easily and flew steadily, showing how efficient a ship tow was in practice. Wind, or lack of it, was simply no factor. Kites with weather instruments aboard could readily be flown well over 10,000 feet in the air – day after day. Thus observations could be compiled and systematized. Weather predicting became standardized and accurate.

The eighth annual meeting of the Historical Kite Symposium drew 50 participants over a long weekend. They heard lectures, toured the museum, and built their own replica kite in on the spot. The model chosen was a Russian weather model invented before World War I by the Russian Kuznetsov. Efficiently organized, the gathering was run by Detlef Griese and wife Elke and by Charles Tacheron and Hilmar Rilling. The Griese couple runs a kite archive, focusing on Europe.

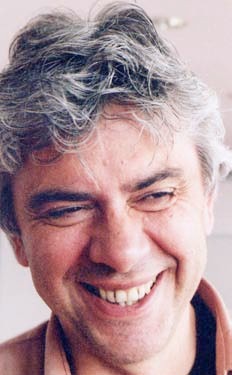

Ben Ruhe. As head of the Zeppelin Museum, Jurgen Bliebler as a perk gets to take the Maybach (see page 7) off display occasionally and drive it around town. “It’s a movable exhibit, publicity for the museum,” he says. He has collected traffic violations with the vehicle. One was for illegal parking, another for speeding. “I was only going 8 kilometers an hour over the limit,” he says. “I paid both tickets,” he says this grudgingly.

New York Times Company. Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Ben Ruhe. Elke and Detlef Griese were the principal organizers of the Historical Kite Symposium’s meeting in Friedrichshafen celebrating the 100th anniversary of the establishment of a weather station in the city.

www.zeppelin.de. The Zeppelin Museum on the busy Friedrichshafen waterfront where ferryboats ply their trade all day. Note museum’s second floor restaurant with its stunning view all the way across Lake Constance to snow-capped Swiss Alps in the distance. On either an educational or tourist jaunt, a small airship floats silently by.

Weather kite flying at Friedrichshafen continued for years after World War I until superseded by the use of aircraft. The kite station a quarter mile down the waterfront from the museum was razed in the Thirties and replaced by an apartment building. The wharf there where the speedy Gna was docked remains, however, about how it was originally.

As an urban renewal scheme, the museum and city are now considering rebuilding the kite station as a combined cultural monument and tourist attraction. The museum also plans to add a considerable kite component to its displays and collection. As well as the many Friedrichshafen industries having a link to Count Zeppelin, his family, scattered across Germany, can be expected to pitch in as well.

Since it packs in the crowds on a daily basis, the Zeppelin Museum would be a first rate venue for a display of kites. With 43,000 square feet of exhibition space, its featured display is a reconstructed 108-foot section of the legendary Hindenburg, the LZ 129, which exploded at its berth in Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937. The elegant rooms on view convey how passengers relished to the full the indescribable pleasure of silently floating through the air in surroundings of great style and luxury. Zeppelins have always been the ultimate in glamour.

Today, the waterfront in front of the museum retains this chic, as ferryboats servicing the dozens of ports up and down the lake scurry in and out of harbor. Tourists and travelers soak in the sun at outdoor cafes. Back and forth overhead, a small, high tech Zeppelin carrying students and tourists floats by in silence. It’s a scene to bring a smile to the face of old Count von Zeppelin.

Ben Ruhe. A “technology transfer” in Friedrichshafen reflected the wide influence of the Zeppelin airships on Friedrichshafen industry. This grand, three-and-a-half ton Maybach automobile from the 1930s was named the Zeppelin. Weighing three and a half tons, it was Germany’s answer to Britain’s Rolls-Royce. It is on exhibition at the Zeppelin Museum as a link to the glamour associated with Zeppelin travel.

Ben Ruhe. A haunting Vladamir Tatlin aerial sculpture in the main hall of the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen pays tribute to the German aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal. Lilienthal was killed flying one of his pioneering gliders. Tatlin, a Russian, was a major Futurist artist.