Stephen Hoskins

From Discourse 17

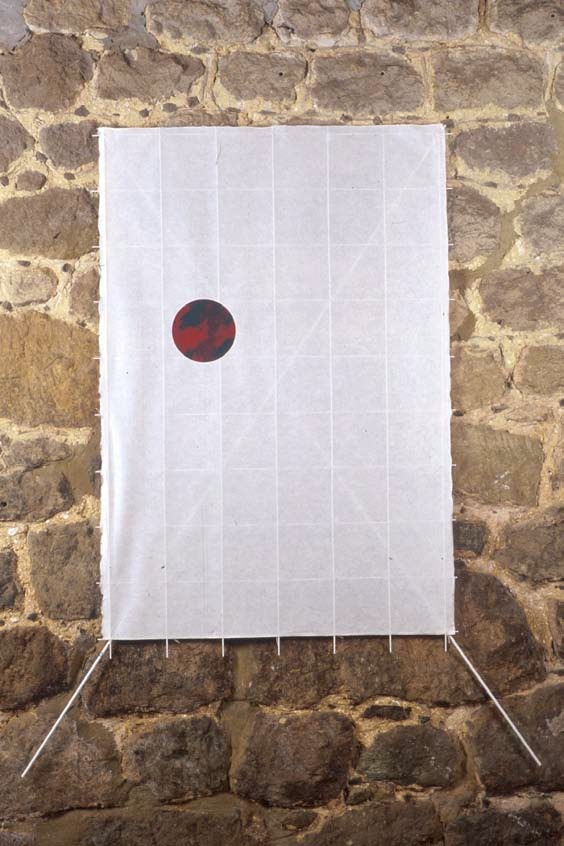

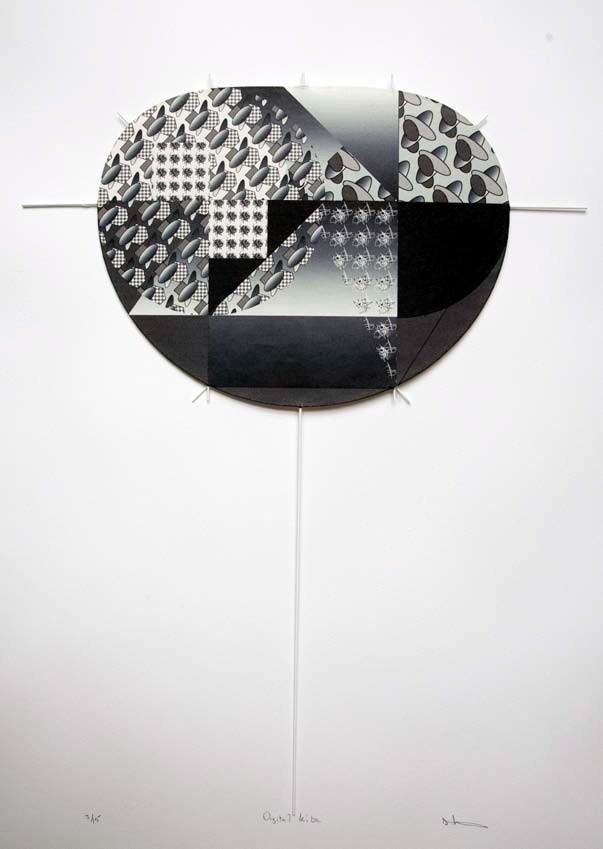

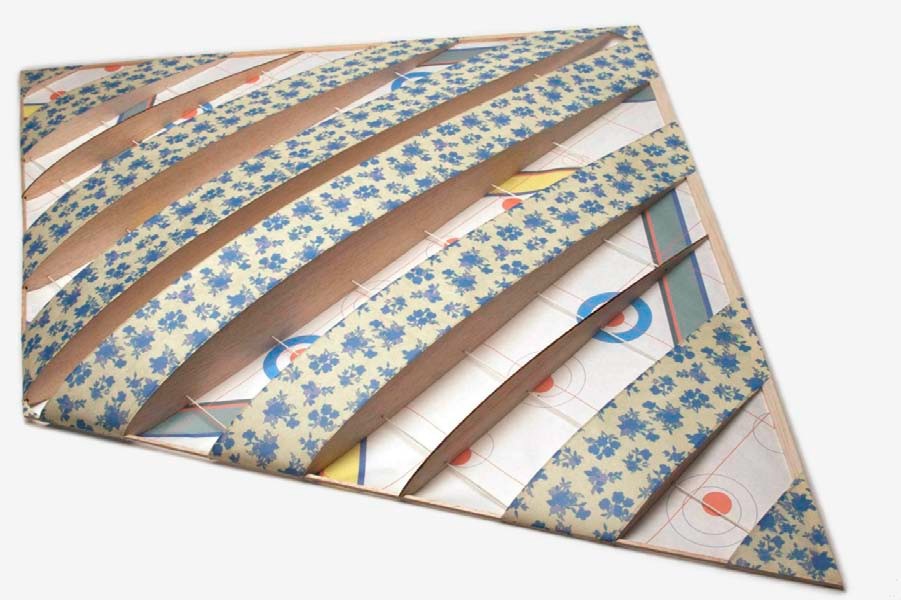

Stephen Hoskins. White Edo: Screenprinted handmade Japanese paper, glass fiber rod, and Dacron thread.

My kite prints are as much about the craft of making as they are a gentle delight in challenging the notions of what constitutes a print and where the perceived borders between the fine and applied arts end and begin. In the U.K. there are still very distinct borders between that which is perceived as art and that which is then deemed craft. A denial of craft skills seems to me as an educator a sad consequence of current trends. Fortunately this view is changing and I find great enjoyment in making craft works that are shown in an art context.

I first came to kites in the mid-1970s with what would now be termed a gap year between my undergraduate art degree and moving on to a master’s program in fine art printmaking at the Royal College of Art in London. At the time I had no studio facilities but had recently discovered David Pelham’s Book of Kites published by Penguin Books, which offered over 50 scale plans of kites from around the world. Inspired by Pelham’s book, I started making kites as a substitute for making art. The first kite I made was a large Malay about two meters (six feet, six inches) across, which was made from red and black nylon (a cheap lining material for coats and dresses, which was relatively air opaque), with wooden dowel spars. Once bowed, it was a beautifully behaved, tailless kite and still one of the best I have ever made for its flying characteristics.

Subsequently I made a series of deltas and colorful rokkakus whilst learning the basics of kitemaking and flying, then really branched out to make a Lecornu’s Box from ripstop nylon with glass fiber spars, which I never managed to fly. Whilst ripstop was a great material for the manufacture of kites, I feel very little empathy for it as a material in its own right, and it certainly has none of the inherent qualities of a beautiful sheet of handmade paper. In addition, it is one of the most difficult materials I know to print on. Glass fiber rod however was a revelation. It was immensely strong, came in a host of different diameters, and was able to bend into compound curves without snapping. Also unlike bamboo, it did not need to be spliced with a knife, thus avoiding the dangerous potential of further visits to hospital when the knife slipped. Once sleeved inside an aluminum rod, the aluminum could be drilled and a split ring passed through, thus making more resilient compound joints.

By this point I had moved to London, and Tal Streeter’s book on the Art of the Japanese Kite became a huge inspiration leading to a combination of kites and art as part of my master’s degree. I attempted making a glass kite by blowing very thin glass and then gluing the pieces together (an impossible task at the end of the ‘70s, but technically quite possible now). I did however manage to make a 1.1 meter (four foot, nine inches) Edo kite from a thin aluminum sheet, known at the time as the “flying razor blade.” I then gave up making kites for nearly 20 years. However I did slowly build a small collection of other people’s kites. Unfortunately I have no documentation of my formative years of kitemaking apart from my memories.

Having taught for many years in U.K. art schools, I did not return to kitemaking until I gained an academic research post at the University of the West of England in Bristol, where I now run a large arts research department. An invitation to take part in an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where we were required to make a piece of work in response to handling silverware from the collection, inspired a new direction. I returned to my earlier roots and made a kite based on an 18th Century toast rack, made from glass fiber rod, wood, and Japanese handmade paper. The flying toast rack allowed the ability to drop 20 years of self-imposed restraints and create work which existed for pleasure as well as presenting some very challenging problems. One was health and safety regulations at the museum: the kite might have fallen on someone’s head, even though it only weighed less than 16 ounces.

Having started making kites again, the toast rack was followed by a one-man show in 1999 of three-dimensional prints (or works) with a very short deadline, thus creating the impetus for a new body of work. The result was an exhibition of prints that fly and kites that were printed. Paying homage to traditional kite manufacture from Japan, Thailand, Nepal, and India, these works were only possible due to a marriage of late 20th Century technology and the unsurpassed quality of a delicate sheet of handmade paper.

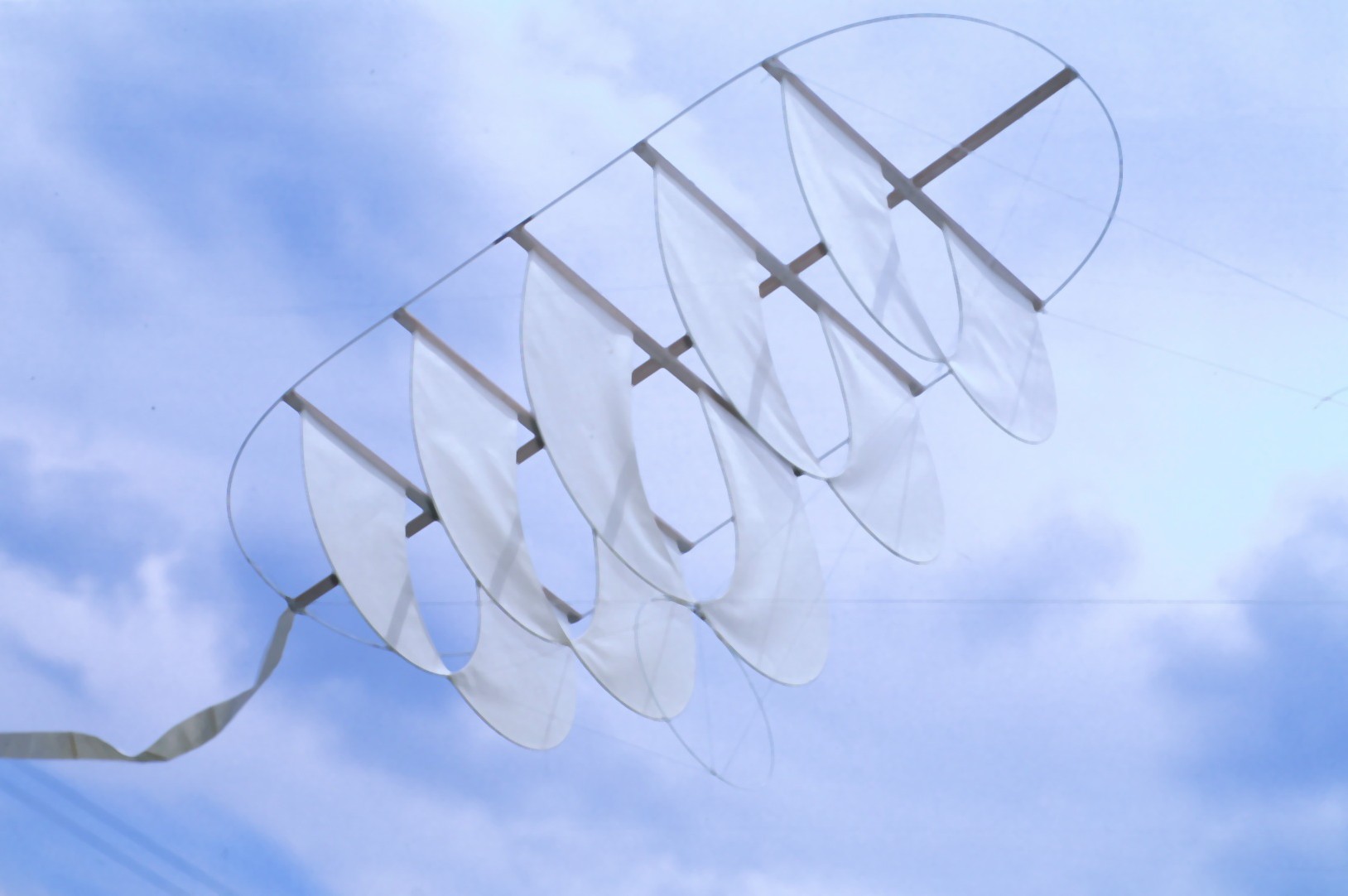

Within the work, the imagery was screen printed onto handmade paper from Japan, Nepal, and Thailand. Only delicate handmade sheets such as these, are capable of being formed around the compound glass fiber shapes used in the frameworks. This is due to the fact that in a sheet of handmade paper, the fibers lie in random directions, unlike a machine-made sheet where, due to the speed of manufacture, the fibers all lie in one direction. The glass fiber rods are tied and glued together using traditional knots. For many years I have used a braided Dacron line that is waxed and holds a knot really tightly. Here again I like the fact that I am mixing a traditional process with a product of current technology.

Stephen Hoskins. Toast Rack: Japanese handmade paper, glass fiber rod, wood, and Dacron thread.

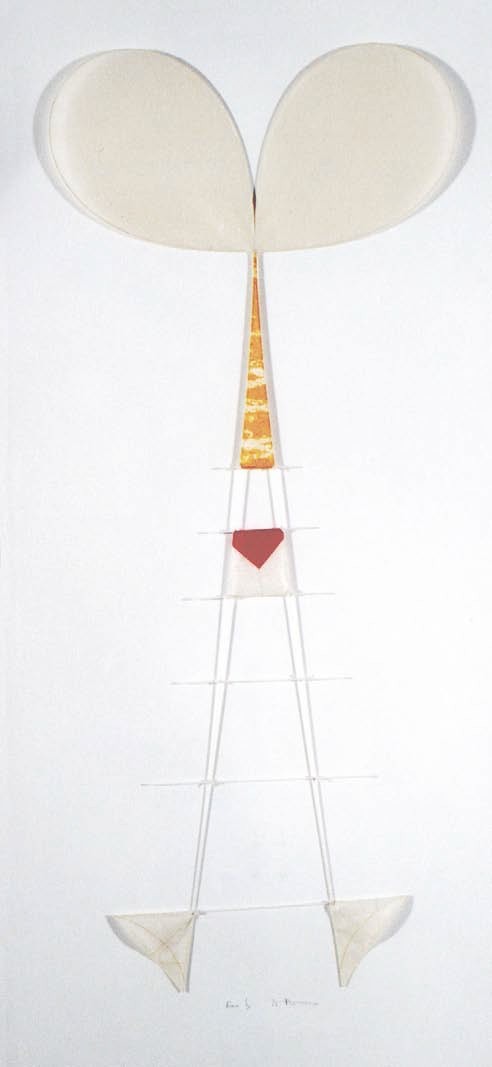

Stephen Hoskins. Ears 1: Screenprinted handmade Japanese and Thai paper, glass fiber rod, and Dacron thread.

Stephen Hoskins. Digital Ears: Inkjet printed Japanese paper, glass fiber rod, and Dacron thread.

Following from the freedom I gained from making the flying toast rack, I first made a series of kites known as “Ears 1, 11, and 111.” Here I wanted to make a self- supporting kite, where one was not sure where the body of the kite was separate from the tail, or whether it even mattered if there was a distinction. The coverings were drawn from a stock of previously printed Japanese and Nepalese handmade papers, gifu shoji and Khadi mulberry.

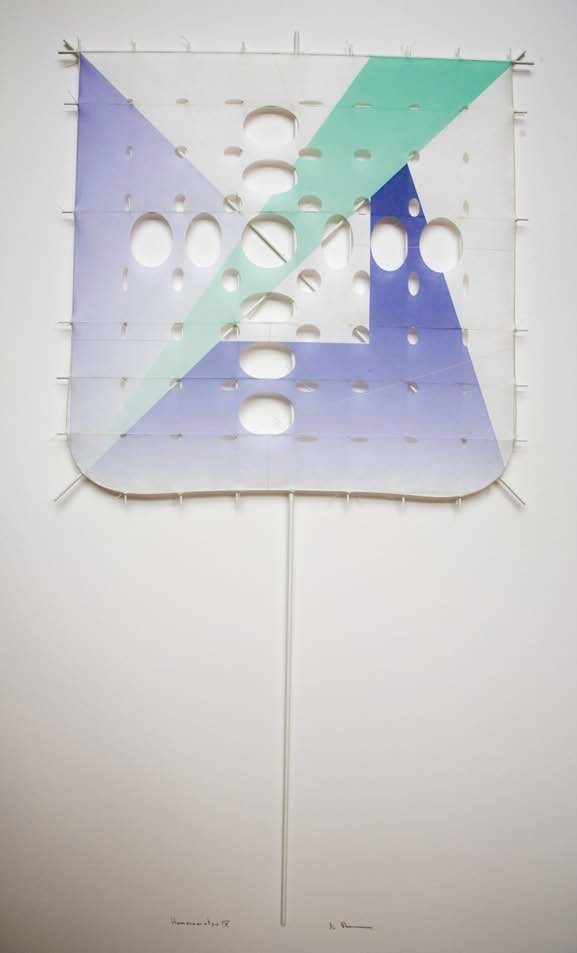

Once a framework is tied together and covered with handmade paper under tension, as can be seen in the Hamamatsu series of kites, it is surprising just how strong handmade tissue actually is, due to the multiple directions of the fibers. It will not only easily shape itself to the compound curvature of the frame when dampened, but is much stronger than a machine-made sheet due to its multi-directional stability. I have had kites where the glass fiber rod is under so much tension that after several years it will suddenly give way and collapse for no apparent reason other than perhaps a change of humidity in the atmosphere changing the tension in the paper covering.

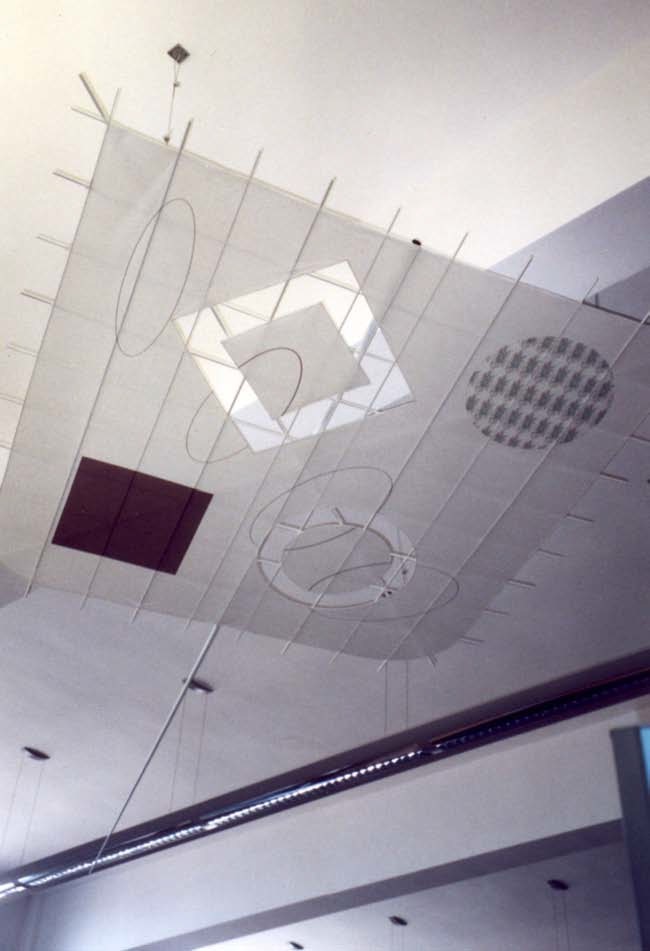

This body of work has sustained various strands of my personal art practice ever since and has run in parallel with developments in new technology that have been adopted by my research center. In 2001 I won a commission to create a series of large kites as a public artwork, which was situated in the offices of a large U.K. bank. I made four kites based upon the Hamamatsu construction that were over two meters (six feet, six inches square) with a tapering carbon fiber central spar that extended for over four meters (13 feet). These kites were too large to easily screen print, so for the first time I used a wide format inkjet printer that printed 60 inches wide, and very lightweight (35 gsm) Japanese paper from the roll sekishu shi. Inkjet printers at this time were not designed to print on such an absorbent and lightweight paper stock. It was like trying to print onto toilet tissue. The problems were overcome by writing a specialist profile to control the printer’s settings and combining this with printing the color at 20% of its full strength. In order to bend the grassfire rod to the desired shape, special jigs had to be constructed to hold the spars in place whilst they were being tied and covered with the tissue covering. These kites were some of the first where I created asymmetric holes in the fabric covering, so that it was obvious they would not fly.

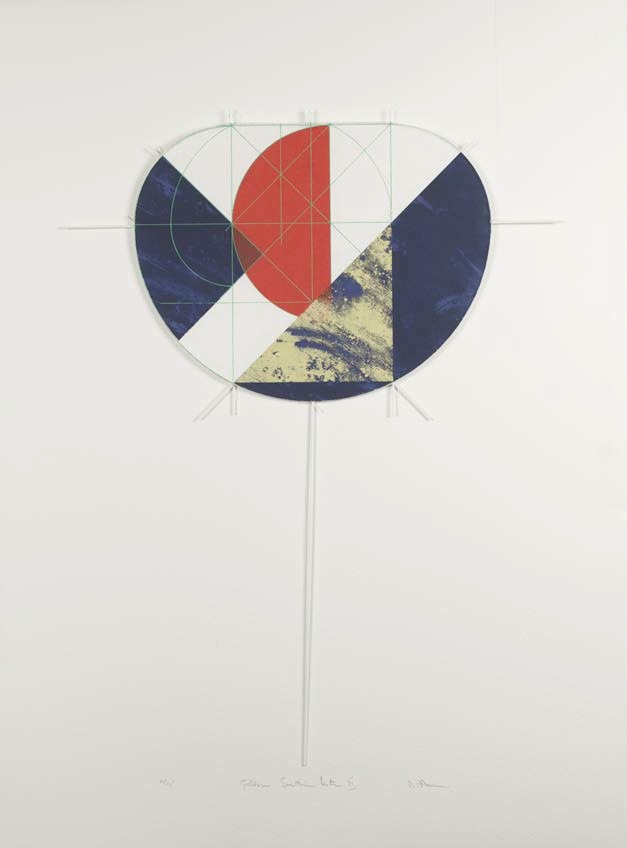

The use of inkjet printing onto handmade Japanese paper spread into a whole series of kites using shapes that I had been using for a number of years. These kites gave me an opportunity to test the potential for digital printing on a number of unusual paper surfaces. In the end I settled upon a sheet of handmade gifu shoji as the paper of preference that gave me a very elegant inkjet-printed result. The imagery used was frequently based on mathematical proportion and Euclidian geometry. The aim was to marry the traditional techniques and technological materials where the precise imagery acted as a foil and counterpart to both. The tactile surface created by printing digital ink upon traditional paper broke away from the distinctive nature of the digital image. Though conceived as prints, it has always been a prerequisite that all the pieces called kite prints in the exhibition and those I have made since are capable of being flown. About half the works were based on traditional shapes with the other half conceived only on the basis that they must have some symmetry and balance in order to fly. The dynamic necessary to make a kite fly inherently creates a different approach to its manufacture. This imposed discipline has a direct relation to the logical order of the geometry and drawings used in the surface decoration. I have always divided the work very deliberately into pieces that are framed (prints?) and pieces that are just hung (kites?). Some of the framed pieces have strings and bridles; most of the unframed work does not. This is a deliberate decision primarily based on the fact that it makes clear that the works are art pieces intended for showing in a gallery context, with the subtext on my part that by not adding bridles to the unframed works, it removes the temptation for me to fly them, thus reducing the possibility for me to break them. I might add I make other kites than the ones in this article for flying, primarily for family and grandchildren.

Having trained as a fine art printmaker, my true love is the physical act of making. In addition, I have an abhorrence of badly made work. I use the term “the craft of making” deliberately. To me, the act of making work is often more satisfying than showing work. I enjoy trying to make an economical structure that has elegance and hopefully a beauty.

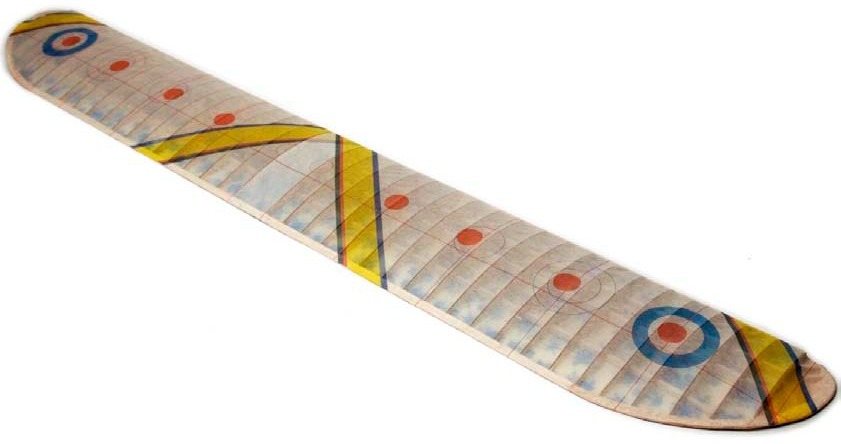

In 2007 I introduced laser cutting for paper, wood and plastics into my research center. I first started laser cutting kite shapes as original prints, initially in a series of miniature prints which are no larger than three inches by four inches (7.5 x 10 centimeters), then into an original print that was a laser cut paper based entirely on an Edo kite with a rabbit and wave design. This was created for an invited Australian artists exchange portfolio entitled “False Gods.” This work was followed by a series of kites with laser cut parts as smaller versions of the large Hamamatsu kites I had made in earlier years. I then discovered the delights of laser cut balsa wood, taking me straight back to my childhood, where I had spent my years from 13 to 17 making diesel engined model airplanes. (My inspiration came from an uncle who had won the national championship control line speed record in 1951 with a model airplane that he then proceeded to do stunts with.) The delight and difference in cutting balsa wood with a laser is the sheer accuracy and speed that is possible with this technique. In my teens it would take at least a day to cut the ribs one at a time with a knife and probably at least another day to assemble a wing. Now I can laser cut a whole wing in 20 minutes and assemble it with super glue in less than an hour. Everything just slots together with no trimming or adjustment necessary (if you have drawn the file correctly).

Therefore I now combine laser cut balsa wood with inkjet printed images onto handmade Japanese paper and carbon fiber rod to make combined kite and airplane structures. I have tried to make the coverings as delicate as possible and I can now inkjet print an incredibly light 13 gsm tissue by mounting it onto a backing sheet and printing it through a Roland solvent printer that we have in the lab. The imagery I use on these lightweight coatings is deliberately decorative and not what you would associate with model airplanes. The current rose imagery is generic and totally constructed in Adobe Illustrator to resemble a traditional chintz pattern. The airfoil sections cut in balsa wood are generic compilations from a series of model airplane plans. My current collection of artworks, shown in the images on page 41, are in the stage of what in the past I have called “works on the way to somewhere else.” In essence they are the early pieces in a series where I am working through an idea. I intend to push the potential of laser cut balsa wood much further and combine it either with CNC milled spars or use traditional steaming to bend spars into unusual shapes.

Stephen Hoskins. Golden Section 2: Screenprinted handmade Japanese paper, glass fiber rod, and Dacron thread.

Stephen Hoskins. Digital Golden Section: Inkjet printed Japanese paper, glass fiber rod, and Dacron thread.

Stephen Hoskins. Newcastle Kites: Inkjet printed Japanese paper, glass fiber rod, and Dacron thread.

Stephen Hoskins. Laser cut Hodamura: Glass fiber rod, inkjet printed and laser cut handmade Japanese paper, Dacron thread.

Centre for Fine Print Research. Model aeroplane wing: Laser cut balsa wood, inkjet printed handmade Japanese paper. 2 m x 20 cm x 4 cm.

Centre for Fine Print Research. Balsa wood Malay with Aerofoil section: Laser cut balsa wood, carbon fiber rod, inkjet printed handmade Japanese paper. 1.5 m x 1.2 m x 8 cm.

For the past seven years I have been working on 3D printing as part of my research. We currently have 11 3D printers in the labs, ranging from the cheap desktop printers through to high quality printers that print in great detail. We are leaders in the field of 3D printed ceramics. I have been trying to find a way to combine 3D printing with kitemaking and art in a way that goes beyond just printing connecting pieces for the spars. Recently we have been discussing the prospect of printing structures similar to feathers and coating them with a thin layer of cellulose, in the same manner as tiny indoor model airplane wings used to be coated. It should then be possible to either print joining sections or find other ways of joining them to make larger kite structures, which I am sure would fly.

The idea of making a kite that is primarily made by 3D printer appeals to me, and may at long last be one way for me to combine my research with my passion for making kites and prints that fly. ◆