Ben Ruhe

From Discourse 15

Simon Bond. Joe Hadzicki and others participate in a mega-fly to commemorate the Rev Kite’s 20th Anniversary in Bristol, England.

A hobby and sport in the West and a religious celebration in the East, kiting became international in the last two decades through increased global travel and because the internet made verbal connections fast and easy. Intelligent patronage by the Drachen Foundation helped these developments significantly. Founded and led by Scott Skinner, Drachen has compiled a vast amount of archival printed information on kites, collected fine kites, educated people about the subject, sponsored workshops by experts, staged exhibits, supported research, collected photo documentation, and created publications. Now with all the information safely placed in manageable digital formats, Drachen has taken a giant step forward. It has made everything freely available via the World Wide Web. Following is a sample of the wonderful world of kite people and events of the first 20 years of the existence of Drachen, as documented in its wide-ranging Journal.

MORE FUN THAN PLAYING IN SAND

An inventor by profession and kite flier as hobbyist, Joe Hadzicki of San Diego woke up one day with a kite design fully formed in his mind. He went to his workshop, built it, and took it right out to fly. On this first trial it performed beautifully. The Revolution was born. Of course known as The Rev, the kite is controlled by four lines, two for each hand. It spins on its axis, or goes left or right. Most notably, it can be put in a screeching dive, stopped a foot above the ground, then flown backwards up into the sky. Although tricky to control, it immediately became the outstanding new kite of the late 20th century.

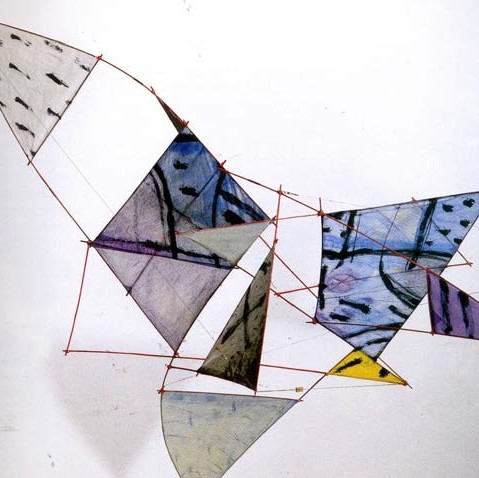

PAINTINGS THAT FLY

A noted artist in his native Budapest, Istvan Bodoczky showed colorful asymmetrical paintings in an art gallery. They were highly irregular, free-form works on paper framed by bamboo strips. In an excess of hubris, he told a critic he could attach flying lines to the paintings and fly them as kites. Challenged to do so, he surprised even himself by succeeding beyond expectation. A new kind of art kite was born. Bodoczky quickly learned how to balance each kite for flight and when word got out about his work he soon was being invited all over the world by kite festivals to show off his strange, wonderful aerial originals.

Drachen Foundation. A free-form, asymmetrical kite by artist Istvan Bodoczky of Budapest. A new kind of art kite was born.

ENOUGH TO MAKE YOU CRY

A designer by training, Anna Rubin saw kitemaking one day and joined in. The result was so successful her second creation made it to the cover of a major kite magazine. A southern Austrian, Rubin seemingly achieves the impossible – her highly original kites make people emotional. Her personal message is so direct and strong, some have burst into tears. As an example, a Rubin kite symbolizing lovers is united by a flurry of red lipstick kisses at the point of jointure. The two joined circles have protruding sticks as a symbol of protection. Its message is immediately clear. As well as a masterpiece of creation, it flies well in addition. “I make a kite to music or poetry,” she says, “I express my emotion. Are my kites feminine? Yes, I can’t imagine a man making them.”

Drachen Foundation. One of Austrian artist Anna Rubin’s highly original kites. “I make a kite to music or poetry,” she says.

MYSTERY ON HIGH

Curt Asker is a Swede living in the south of France who gained world fame by representing his country at the highly prestigious Venice art biennial. His field is illusion – kites suspended from kites flying far above, indoor creations that hang from the ceiling and move in faint wind currents, casting elusive shadows. Under certain light, the shadow is visible but the object not. His great invention is a visual double take: a big X in the sky that marks a spot. Or does it? The X form is see-through, with sky and clouds visible only. The kite actually is the border of the X, blending into the scene. The creation is spare, strange, original, somehow profound.

Ben Ruhe. Artist Curt Asker’s “X marks the spot in the sky” kite. “I work with the sky, “ he has said, “I don’t impose on it.”

SKY WARS

Kite flying is an old, popular sport in Thailand, so much so that a giant tract next to the royal palace is designated Kite Field. King Bumiphal, in his younger days, was an active participant. As the hot weather approaches, the monsoon wind becomes perfect for flying during the late afternoons of the month of February, and people turn out in droves daily to watch traditional warfare in the sky. A well organized game pits masculine chulas against female pakpaos. Each tries to down the other, with the former using large size and weight and the latter small size but clever wiles to score. (Surprisingly, the pakpaos win a majority of the jousts.) Teams are sponsored by local businesses and flying is done over the years on a traditional father and son basis. A winner in each category is declared at the end of the season. Teams are big and well organized with as many as 25 players on a side. And they are ruthless. Spectators can get run down by a squad of racing boys carrying a pulley to haul a hooked rival down to the grass. All of this is accompanied by shouting, sirens, bugle blasts, and loud gambling yells. Competition ends each day when a sudden sunset occurs. No worries. The teams and crowds will be back tomorrow.

Drachen Foundation. A traditional Thai chula kite. Kite jousts pit large, masculine chulas against smaller, female pakpaos.

THE PETER LYNN PHENOMENON

Peter Lynn of Ashburton, New Zealand makes and flies his mega demonstration kites worldwide. By now, he has racked up more air miles than some veteran Boeing 747 pilots. He particularly shows off his world’s largest kite, so powerful it is anchored by a loaded dump truck. Nobody can top him, because he simply attaches added wing material to his mattress-like creation to make it ever larger. Not surprisingly, this 75-by-120-foot giant is sponsored by Arab oil money. Lynn also owns the oldest known kite in existence, found under a floor in a Dutch house being razed. It has been accurately dated to the end of the 18th century. Ever one to promote new kiting, Lynn is foremost in pioneering kite propulsion for boats and surfboards. At this stage, this sport is thrilling stuff to watch but only for the brave to practice. A gust, for example, can lift a boat halfway out of water.

Peter Lynn Kites. The first flight of Peter Lynn’s Mega Ray demonstration kite, the largest kite in the world.

SAVING TRADITION

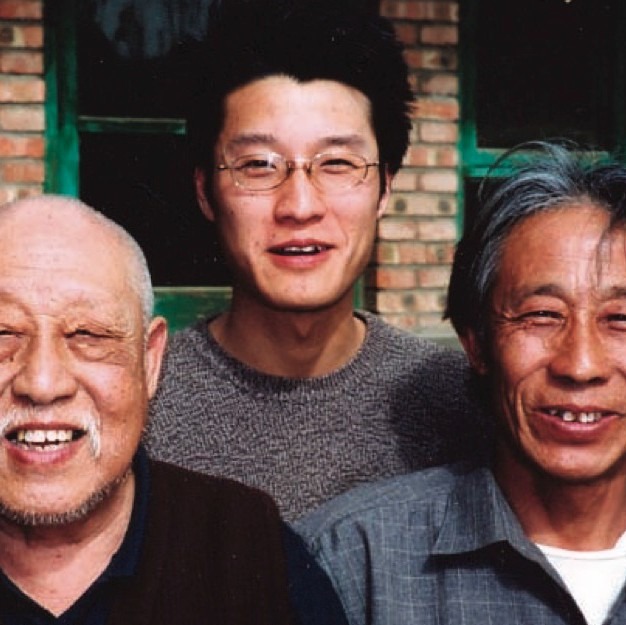

As the 75th generation descendent of the sage Confucius and also a famous kitemaker, Kong Xiang Ze was a doubly marked man when Chairman Mao declared old traditions were to be destroyed during the Chinese Cultural Revolution begun in the mid-1960s. “I was beaten seven times and repeatedly publicly humiliated by Red Guards,” Kong recalls. “My property was trashed. I had no work.” Helped by family, Kong somehow survived and eventually saw the political climate change. By the late l970s, he was able to make and sell kites again and live a family life. He began to be famous again as well. Now in his 80s, he lives with his son and grandson in an isolated ex-commune north of Beijing – still making a variety of kites, especially the beautiful Beijing swallow. “The evil days are long gone,” he says; “I’ve become objective.” He smiles.

Ben Ruhe. Kong Xing Ze (left) is patriarch of a kitemaking family. Son Ling Min and grandson Bing Zhang are great masters too.

MOST BEAUTIFUL

Without question, the world’s most beautiful kite is the wau of Malaysia, with its beautiful shape and jewel-like pattern. Made in the impoverished, back-of-beyond state of Kelantan, the wau kite is well known internationally through its use as a symbol by Air Malaysia. Making one is painstaking work taking weeks. Using a razor-sharp homemade knife, a stiff piece of colored paper is cut into the shape of an intricate kite sail, then a pattern cut into it. This cutout is pasted to the original backed frame. Next, another piece of paper in the same shape but different color is cut into a different pattern and pasted atop the first cutout. Subsequent layers, up to eight and all in different colors, give the creation a detailed, very colorful appearance. Images are always abstractions, as dictated by the Muslim Koran. Ismail bin Jusoh, a master, says, “Kites are beautiful, challenging to make and fly. They can even make an old man like me feel young again.” His granddaughter, age 12, bookends the business. A math whiz, she keeps the books.

Drachen Foundation. The beautiful Malaysian wau kite is painstakingly made from many layers of colored paper over weeks.

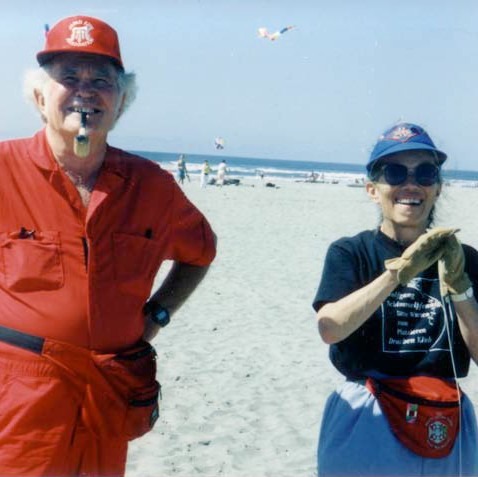

BETTY AND BILL IN ACTION

Enamored of kites and reasonably solvent, Texas Tech professors Betty Street and Bill Lockhart decided to hold a kite workshop at an unused university football camp in the backwoods of West Texas. Keeping things as simple as possible to hold down costs, they drew an enthusiastic crowd and when they realized they had broken even, they decided to do it again. Thus was the annual Junction meeting established. When they received patronage from the Drachen Foundation, they began inviting foremost figures from kiting around the world to join in and teach and the fame of Junction grew. Facilities were open around the clock, so it was not unknown for fliers to be out at 3am testing their kites under the West Texas moon, under the watchful eye of armadillos. Breakfasts ran to grits and gravy, to maintain state tradition for good food. As Drachen president Scott Skinner observes, fliers came initially to make a kite but soon grasped that Junction was really all about learning and good fellowship.

Drachen Foundation. Bill Lockhart and Betty Street, the Texas Tech professors who founded the annual Junction Kite Retreat.

STOOPING TO CONQUER

Dr. David Scarbrough recalls the very day of his inspiration. Up in the air doing parasailing on July 10, l994, this avid falconer realized he was actually flying when strapped to a kite and that he could apply an insight he had just had to his sport. Scarbrough, a dentist from Fairfax, Missouri, reasoned that he could solve one of the great problems of the age-old, little changed sport of falconry: how to get his low-flying peregrine bird high enough to make a dramatic and loud dive or stoop. He would simply dangle food from a kite and take it up to 1,000 feet, the hungry bird to follow. There was no point to going higher; the hawk would be out of sight. The stoop of this bird is high drama. Reaching a well documented speed of up to 200 miles an hour, the diving peregrine becomes the fastest bird on the globe. It is going so fast it just strikes a pigeon as it whizzes by. Grabbing the bird at that speed would rip off a claw. Knowledge of Scarbrough’s new training method ricocheted around the world. Scarbrough looks back on his insight with great pride. He realizes he has made an authentically profound contribution to the sport he loves.

Eric Keith. Dr. David Scarbrough, an avid falconer, used an insight from parasailing to improve falcon training with kites.

Ben Ruhe. Artist Jackie Matisse demonstrates her concept of kite tails flown underwater with paper suspended in glass bottles.

TOUCH OF FAME

Her grandfather (Henri Matisse) and stepfather (Marcel Duchamp) were two of the most famous artists of the 20th century, so Jackie Matisse needed to find her own art niche, which she did – kites. A tall redhead. Jackie was raised in New York City and is more American than French, although she now lives in a spacious compound near Paris, complete with lots of highly valuable art – paintings by her grandfather, ready- mades by Duchamp, and an assortment of other choice work by famous friends of the two. Duchamp’s chess gear, including table and timing clock, are on view. Although divorced, when traveling she sticks with her married name to avoid the complications of fame. Matisse makes and flies kites striking for their long tails. She is also very experimental, having flown underwater. Some of her small kites grace bottles of water, where they sway with gentle motion. She has even achieved convincing computer mockups. She has taken kite art into the computer age.

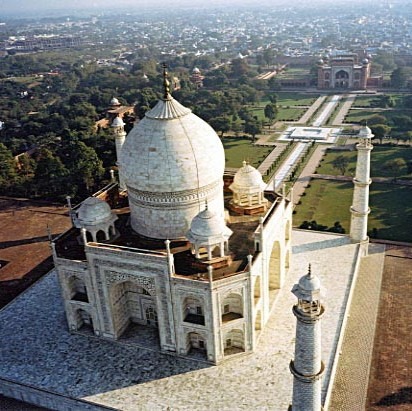

PHOTOS FROM ON HIGH

Cheap, low maintenance, highly personal, unobtrusive, flyable in conditions that would defeat competition such as balloons, the kite is a wonderful platform for photography. By acquiring several different kites for different wind conditions, the photographer can operate at any time and virtually anywhere. Nicholas Chorier, a high spirited Frenchman from Montpelier, has long been a convert and has turned out dazzling coffee table images. He has traveled the world and documented some off-limit subjects. Shooting the Taj Mahal in India, he got himself arrested for endangerment. The next time he took to the air there, he was a paid employee of the local tourist commission. That’s the way things go with him. Chorier has particularly loved India for its rich and diverse scenery and crowds in the hundreds of thousands for a festival, of which there are many. Kites attract numerous fans but reward few with paid employment. Chorier is one who has figured out how to do something he loves while making a living at it.

Nicholas Chorier. A kite aerial photograph taken by Nicholas Chorier in India.

THE ONE-MAN BAND

When George Peters of Boulder, Colorado sets up his whimsical monster creations (and other kite stuff) at a kite festival, within minutes it appears six people are at work and not just one. “How can any one person carry so much gear?” is the question viewers ask. Where does all this colorful flying junk come from, this controlled chaos?

Drachen Foundation. A whimsical George Peters kite.

In a roundabout way, Peters himself provides the answer. Asked in a questionnaire his interests (other than kiting), Peters produced some accidental, revealing poetry. He responded: “I like: the color blue (as in the sky), reading, writing, but not arithmetic, waking up, looking up, long walks under the trees, sitting on rocks, seeing how long I can hold my breath under water, painting things to make them look different, making things better and better. I like my cat and my dog, interesting rock formations, interesting architecture, travel, cloud formations out the window seat, making fun of other people’s walks, primitive weaponry (especially blowguns and boomerangs), lead animals, old toys, the eternal quest for the perfect pen, miniature things, odd postcards, sailing, drawing, doodling, making useless things, finding useless things.”

KITES FILLING THE SKY

Makar Sankranti is a Hindu Indian festival in January celebrated all over the country by the flying of kites. This being India, to say it draws crowds is a real understatement. In Jaipur alone, in the north of the nation, an estimated million people climb onto the flat roofs of the desert community to party and to fly their little fighters. The kites have glass shards glued to the line so they cut the line of any other kite they encounter in the sky. At a recent festival, one determined flier had 75 kites stacked up beside him, ready to go. These paper kites are cheap and easily made and he obviously expected to cut and be cut very frequently during the long day. One young medical intern politely watched his revered doctor father elaborately prepare and launch a fighter. The son promptly launched too and slashed his father’s line. “Oh, excuse me,” said the son.

Drachen Foundation, In India, kite fighters fly from roofs during the festival of Makar Sankranti, cutting each other out of the sky.

There are so many kites downed that trees are draped with them, looking like Western Christmas trees. A less agreeable element is the deaths. Although the kites cost only pennies, children still can’t afford them so they recklessly pursue cut kites falling to earth by jumping from rooftop to rooftop. Some of the leaps fall short. Downed kites also slay motorcyclists when lines drape themselves across the necks of the speeding drivers. Deaths reached more than 100 in the city, as reported next day in the local paper. Sliced fingers were in the thousands. That’s Makar Sankrati for you.

STAINED GLASS SKY WINDOWS

Drachen Foundation. The barrilietes gigantes, or giant kites, of Sumpango, Guatemala look like stained glass windows in the sky.

One of the great sights in the global kite world is the giant kites of Sumpango, a Guatemalan village – stained glass windows in the sky, as they have been called. Taking weeks or months to construct from many layers of colored tissue paper with backing, they are on view just one day – the Day of the Dead on November 1. Graves of the dead are refurbished by families in the morning, then kites displayed and flown from a nearby soccer field. The religious rite quickly evolves into a village festival, drawing many thousands of spectators, most of them locals. While paying honor to the dead, the kites these days tend to make something of a political statement as well. Built by young volunteer Maya Indians, they have messages that protest the repressive treatment of the Mayas over decades by the ruling Ladinos. The kites are so big – up to 40 feet wide (bigger than that is forbidden) – most remain unflown because of the safety factor, although smaller kites dot the sky to show that even in calm these round kites will perform. Edged by active volcanoes, the soccer field develops a picnic atmosphere with talk, food, drinks, carnival rides, nonstop music, and of course the kites. It is altogether a brief but memorable celebration. ◆