Walter Diem

From Discourse 4

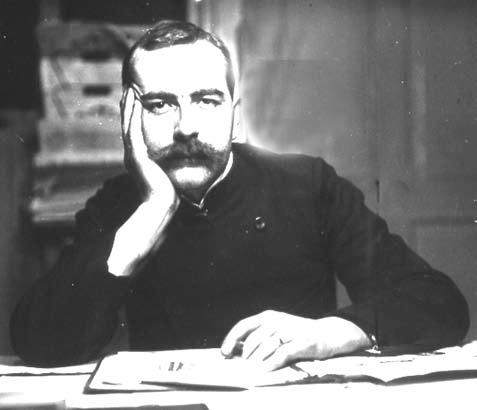

Margarete Steiff GmbH. Richard Steiff, creator of the Roloplan, who remains outside Germany almost unknown as a kite maker.

For many European kite enthusiasts, the Roloplan is a kite they consider just as important as the Hargrave, the Eddy, or the Cody. It is interesting for collectors because many original examples of it still exist and have been traded time and again. Small wonder: the Roloplan was manufactured from 1909 to 1943 and again from 1950 to 1968 in altogether twenty different sizes!

Scarcely any other kite has been similarly available. In addition to the copyrighted mass production, directions for the construction of the Roloplan were published in a number of craft books from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Hargrave, Eddy, Cody. You read the names and immediately you visualize the appropriate kite. Behind the Roloplan also stands a name, but he remains outside Germany almost unknown. Richard Steiff, the maker of the Roloplan has become famous worldwide for another product: he invented the Teddy Bear. He also designed factory buildings for the Margarete Steiff Toy Factory, managed for a time – from 1903 to 1910 – by him, which buildings’ steel and glass construction were at the time a sensation, and which today are still in step with the times and are used for production with minimal technical improvements. They can be considered an anticipation of the Bauhaus style.

This Richard Steiff was a man of many talents. Born on February 7, 1887, in the South German town of Giengen, he went, after finishing public school, to a commercial art academy in Stuttgart, completed a longer stay in England afterward, improved his language skills, and then at the age of twenty, joined the firm of his Aunt Margarete Steiff. Margarete Steiff produced small plush animals in her modest atelier, and had at first only middling success, even though she called her enterprise “Felt Toy Factory Margarete Steiff.” It was Richard Steiff who brought a change in fortune with his genial idea in 1902. He designed a toy bear with movable parts and a head that could be turned, and gave him a tuft-like fur that resembled a real bear’s fur. Margarete Steiff and other manufacturers of that time already did produce toy bears, which could neither move their heads nor their legs. Richard Steiff’s idea brought movement to the toy and also to the market – although at first, success remained in the offing. At the toy fair of Leipzig in the spring of 1903, the new bear was barely noticed. Only just before final closing, an American buyer discovered the new toy, bought the last exhibition pieces, and ordered 3,000 of them.

At the same time in the US, a small bear was being produced that had been created from a cartoon in the Washington Post of November 16, 1902. The caricature depicts the US President Theodore Roosevelt, who is supposed to have refused to shoot at a small, defenseless bear while on a hunting party. But the Teddy Bear was the first Steiff product to become known and loved throughout the land.

Already in the first year, 12,000 copies were sold in the US, where they got the name “Teddy.” Theodore Roosevelt’s nickname at that time was “Ted” or “Teddy.” And still the Teddy Bear bears that name today.

Since, with the success of the Teddy Bear, the production of the Margarete Steiff Toy Factory rose almost overnight, new employees had to be hired and a bigger production space was needed. Richard Steiff, only 26, sought a solution to this problem. He sketched the plans for buildings which could be constructed quickly and at the least possible cost. For Richard Steiff, the most important thing was that the female employees, who produced the plush animals by hand, be able to work in bright surroundings, which not only contributed to their personal comfort but also to greater productivity and with fewer errors. To this day, these clearly arranged and unornamented buildings are in use.

Richard Steiff, together with two brothers, was manager of the company founded by their Aunt Margarete, and in spite of the stress, Richard maintained a wide open curiosity. He occupied himself with the experiments of Otto Lilienthal, who had written his study, “Birdflight as Foundation for the Art of Flying,” in 1889. Lilienthal had brought to pass the first glider flight of a machine made by himself, but had suffered mortal injuries in the crash of his glider in 1896. Like Lilienthal, Richard Steiff experimented with kites and other flight objects. He was not the only one who gave thought to creating a machine with which a human being could fly. The kites of Hargrave, Eddy, and Cody grew from the same intention – although they were at best “chained” ascents. No flights were possible with these machines.

The result of Richard Steiff’s experiments was the Roloplan, whose prototype was ready in 1908 and which went into mass production in 1909. (It has been passed down that Margarete Steiff was not at all convinced by these ideas of her pet nephew.) With the name Roloplan, a patent was applied for, whereby the name was to signify that it was on the one hand derived from the word “Aeroplan” (for airplane) and, on the other hand, would signal that the kite could be rolled up.

The special attributes of this kite were its equal length and breadth. The sail of the first Roloplan was divided in two, later in thirds, and therefore they were tagged 120/2 or 180/3 – the first number signifying length (or breadth), the second the number of panels or sails. The sails, made from a light cotton material, came in the color combinations of yellow/red, red/blue, and yellow/blue (but other firms were able to order and fly advertising kites with other colors and their firms’ logos). The frame rods or sticks are found in pockets; the pocket for the length stick is always sewn onto the front side of the panel, and, like the reinforcements at the ends of the pockets, are of brown twill. The sides of the sail are reinforced on the back side by narrow bands always sewn on with a characteristic zig-zag stitch. Over the openings for the insertion and removal of the frame sticks are sewn ties, always arranged on the right side and beside the pocket for the length stick.

Margarete Steiff GmbH. Richard Steiff as young designer.

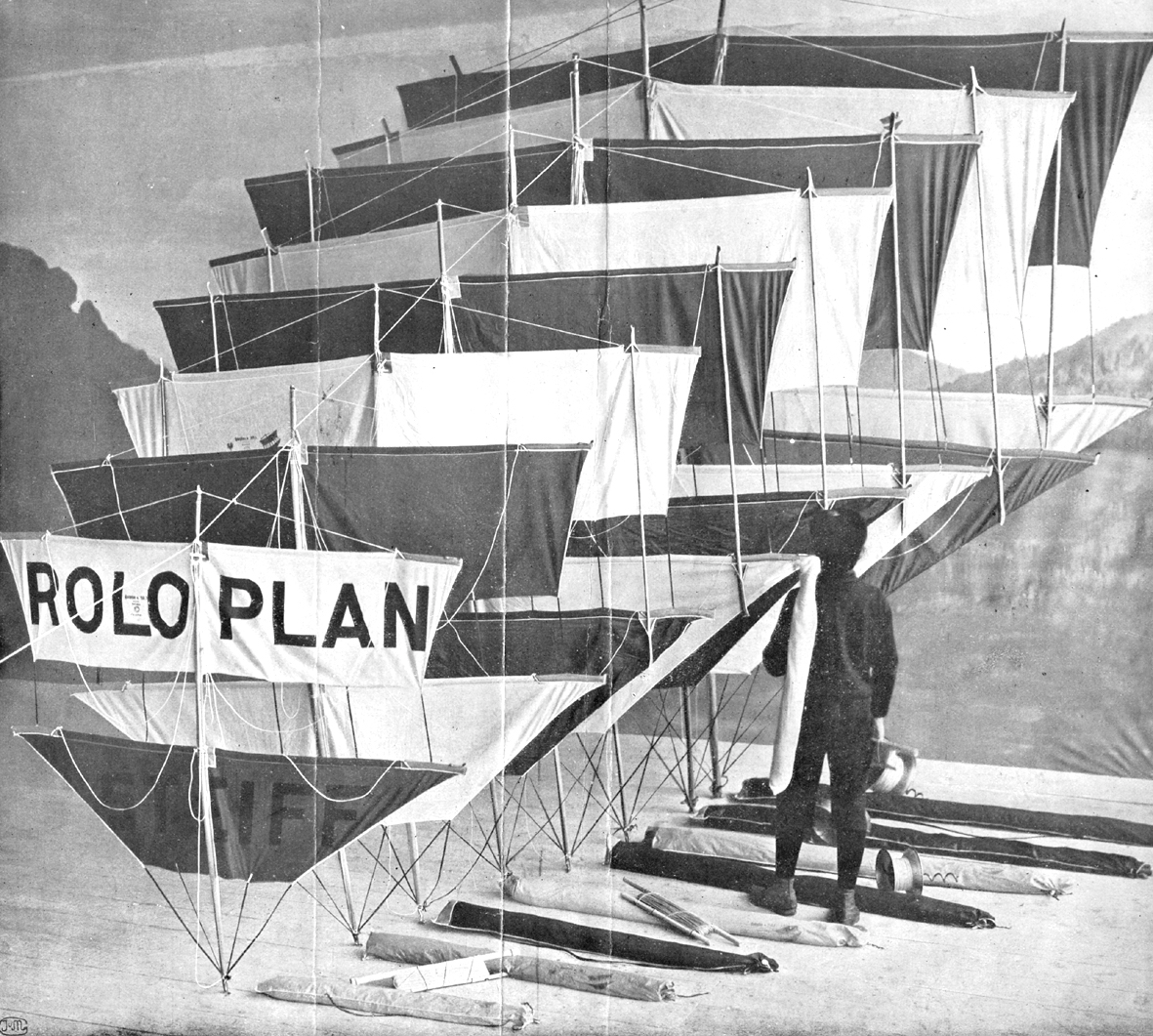

Margarete Steiff GmbH

The Roloplan was manufactured in the following sizes: 80/2—90/2—100/2—120/2—150/2—180/2 and 180/3—210/2 and 210/3—240/2 and 240/3—270/2 and 270/3—300/2 and 200/3—330/2 and 330/3— 360/2 and 360/3. In 1910, a size 720/3 was also manufactured for a short time.

Not all formats were produced at all times. The Roloplan with three sails, for example, was manufactured only from 1910 to 1939.

The Roloplan was and is a wonderful flying machine in all its sizes and has enormous advantages over the kites produced at that time. Richard Steiff was a clever marketing expert (even though this designation didn’t exist in his day) who took care that these qualities became widely known. Steiff took part in many flight contests on the European continent with the Roloplan in order to advertise his kite and to further sales. He garnered numerous distinctions with which many sales pitches could be formulated for the kite. The Roloplan won prizes for the highest flight, biggest capacity, for stability, and also for flight photography. In this, hewas a pioneer: he designed a camera support or “tripod” for the Roloplan that was fixed on the kite string under the kite and which could be released after a time via a glowing tinder. There are a great many photos upon which, by such means, the factory grounds in Giengen were pictured.

Photos are also known that show Richard Steiff in a basket in a manned ascent. In another photo, Richard is shown under an arc of two dozen Roloplans, like the one Eiji Ohashi “invented” many decades later. And he experimented with a machine like an airplane that had a span of nearly twenty meters. He had to discontinue these attempts due to the high cost. On many photos the Roloplans can be seen with the company name printed on them: advertising by kite was nothing unusual at that time.

Kites continued, even after the invention of the Roloplan, to keep Richard Steiff involved, particularly after his overwhelming success in many European countries. There is evidence of this in an album of the Steiff family in which snapshots are contained, taken at different seasons, in which photos can be seen that are also used in the instructions for setting up and taking down the Roloplan. One can see a variety of air snapshots taken with the aid of the Steiff photo “tripod.”

But the sensation in this album is the photos of twenty kites, unknown or barely noticed until last year. Of the pictured kites, only two have been reconstructed by kite enthusiasts. The photos originated during the last two years before World War I. They show these kites in black and white (and heavily darkened) in flight, isolated from any other objects from which the size of these kites might be estimated.

In these kites, Richard Steiff varies the form of the Eddy kite (with which he must have been familiar). He changes the form of its sails in three designs, but leaves their proportions unchanged. For other kites in the photos, he plays with the basic form of the square and separates it, like with his Roloplan, into two to four partial planes. And finally Richard Steiff takes the hexagon and varies it with differently formed partial sails in yellow/red or red/blue (minimal differences in the brightness of the sails show that two different paints were used). We can see in these form variations how Richard Steiff, who had trained as a draftsman, sketching playfully, further developed each of three basic forms and thus found way surprising new sail panels for flat kites. Deviations from these geometrically accentuated forms yield a stork, a butterfly, and a bird shape.

He certainly would have sketched yet other forms among these creative drawing exercises. Perhaps still more kites had been built after these designs and were tested by the co-workers in his firm. Presumably Richard Steiff photographed only the truly flight worthy models.

Because the Roloplans reveal unmistakable characteristics, and because it can be assumed that Richard Steiff also employed for these test kites the same characteristics (for which there is proof in a very few photos), I thought, almost 100 years after the flights documented by the photos, I would reconstruct the kites and present them to interested kite enthusiasts.

I now have two kite builders for the practical work, people who have a name in Germany ( and abroad as well) as knowledgeable about the Roloplan: Werner Ahlgrim, who also had a part in the writing of my earlier book, Kites with a History, and Wolfram Wannrich, who developed the plans for a replica series of the Roloplan several years ago.

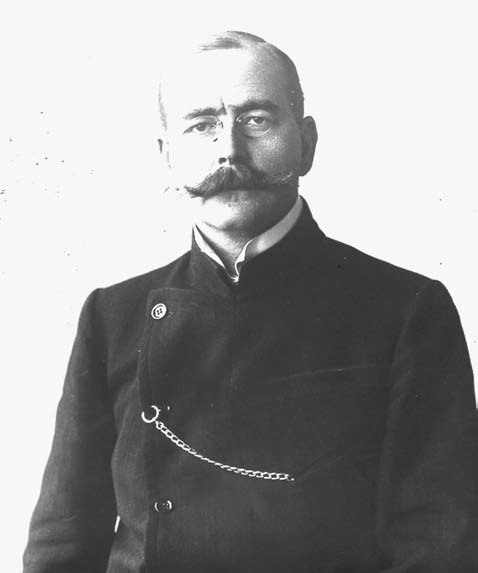

Margarete Steiff GmbH. Richard Steiff as managing director of the Margarete Steiff Toy Factory.

Through this cooperation, seventeen kites were created, which are presented in my book, The Kite Designer Richard Steiff [1] with detailed construction guidelines. I call them original replicas, because the old photos offer no information about the size of the kites. We oriented the new/old Steiff kites to the familiar dimensions of the Roloplan and chose as length 210 cm for most of the models. Some kites are 240 cm long; in one case, I chose 270 cm as length. The most work had to be done when the length of the balance ties had to be determined. One could, of course, tell rather exactly from most of the old photos how many balance ties on which places of the kite body were fastened; but it took many attempts before a co-worker on this project, Ludger Gruss, had so arranged the balance ties that the kites safely flew the way we know the Roloplan flew.

The kites have proven themselves in rather mild wind velocities and in higher wind velocities at the kite festival of 2008 on the Danish island Fano.

The political conditions before, during, and after World War I in Germany and in other European countries were not such that Margarete Steiff’s offer to introduce new kites could be acted upon. Richard Steiff therefore made do with his most successful model, the Roloplan, and with his central assortment of plush animals and mechanical toys. In the 1920s and 1930s, only simple kites in the airplane and bird forms were offered to supplement the Roloplan in its different sizes. Richard Steiff was only involved with the kites from a distance, if at all, for he emigrated with his family in 1923 to the US. It was mainly for health reasons that Steiff withdrew from the management of the company. To be sure, the Margarete Steiff Toy Factory was the most important employer in the town of Giengen, for in almost every family at least one member worked for Steiff. This meant an immense responsibility, under heavy pressure, that impelled Richard Steiff to work hard. As a young man, he had already acquired a good knowledge of the English language and was able to adjust quickly to life in the US. With his resettlement, he also wanted to be nearer to the market that he considered especially important for the sale of Steiff animals. He wanted to observe on the spot trends that could have an influence on his company’s collection. He wanted to align the new plush animals in form and color with the taste of his most important consumer market. For him, the kite theme was now completed, except for the comparatively simple bird and airplane kites that were offered along with the Roloplans.

Thus, important ideas came from him to Germany. He himself felt at home in the US. He won many friends and had an open, hospitable home. Yet his health problems continued; this genial kite designer died on March 30, 1939, in Jackson, Michigan, at the young age of 62.

Translation from the German by Robert Porter

[1] Walter Diem’s book on Richard Steiff, Der Drachendesigner Richard Steiff (The Kite Designer Richard Steiff), is available for sale. For more information, please contact the author directly at diemhamburg@t-online.de.