Ben Ruhe

From Discourse-2

Ben Ruhe. Dorte and Frank Schulz.

DORTE AND FRANK SCHULZ’S WEBSITE WWW.SCANDINAVIAN-KITES.DE

Encouraged by a modest Drachen Foundation grant, historical kite enthusiasts Frank and Dorte Schulz, of Buxtehude, Germany, began researching early Scandinavian utilitarian kite – kites used for meteorological, military and amusement purposes. They planned to combine their love of Scandinavian holidays with a bit of scholarly study, Frank’s long-time interest.

They soon focused on weather kite research alone as being a big enough challenge to study and found it in fact to be a much larger field than they suspected. Now, after three years, they have compiled more than a yard of academic files and pictures, plus 20 books on the subject, and turned up excellent leads to unknown or forgotten projects from a century ago. They see the study going on for years.

Either with personal visits or via postal correspondence and e-mail, the couple has so far documented turn-of-the-last century weather kite studies in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Greenland. They discovered that this early research was basically carried out by a small number of rich men who financed and coordinated the work in Europe and America. Names like de Bort, Rotch (from Harvard’s Blue Hill, near Boston), the Wegener brothers Karl and Alfred, Kusnetsov and Amundsen. Systematizing global weather studies was the goal of these men. These studies continued until the airplane replaced the kite and balloon as weather research tools.

Frank Schulz. German scientists studying the weather in Greenland during a 1906-8 expedition there store a kite in a kind of simple garage built of wooden planking. Protection against wind and snow was achieved without dissembling the kite.

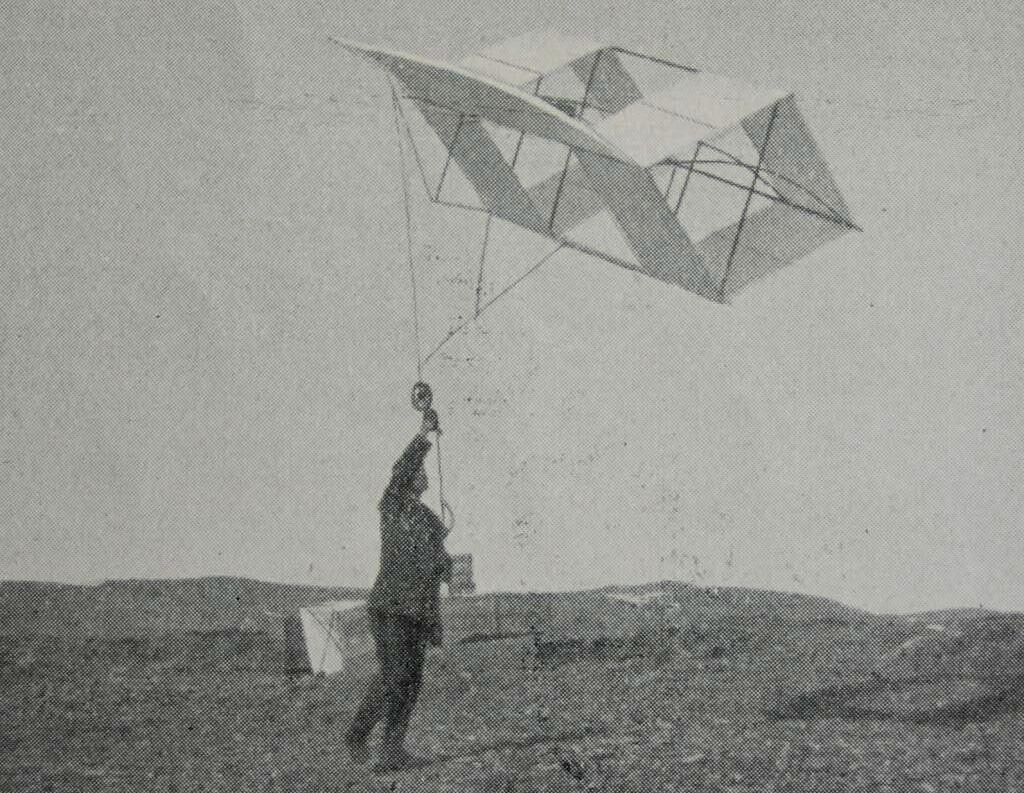

Frank Schulz. Arctic explorer and meteorologist Alfred Wegener prepares to fly a Diamond Boxkite during a German expedition to Greenland in 1906-8. The kite carried instruments used to monitor the weather.

The couple’s Norwegian study focused on Roald Amundsen, famed as the first person to reach the South Pole. The German Kurt Wegener led research in polar Spitzbergen in 1912-3. A weather station at Viborg, Denmark, did its studies in 1902-4. It was directed and financed by the Frenchman Teisserenc de Bort, who earlier used high flying unmanned balloons to discover the stratosphere. Kites were routinely flown as high as 16,000 feet at Viborg. The Schulzes put together 110 pages of documentation on this station alone.

Germans made three separate weather expeditions to Greenland. Because of its vast size and difficult climate, they used boats and established short-term camps on shore, before moving on to new sites. Expeditions were made in 1906-8, in 1913, and again in the early 1930s.

A student of polar air circulation, Alfred Wegener led these forays. They helped lead him to the discovery of the jet stream. Wegener became globally renowned for his theory of continental drift, only proven two decades after his death in 1931 in Greenland. The continental drift concept, which Wegener formulated from his climate, land features, and fossil studies, led directly to the theory of plate tectonics and Wegener was quickly recognized as a founding father of one of the major scientific revolutions of the 20th century.

The earliest weather station so far investigated by the Schulzes was located at Llmala, Finland, near Helsinki, begun in 1900 and operated through 1925, except for a World War I break. It was financed by the Russian government and directed at one point by a Russian named Kutznetsov, inventor of the weather kite that bears his name.

Although German-speaking, Frank and Dorte found their reasonably fluent English was the language most useful to them in their research. Dorte, in addition, contributed knowledge of Danish, which works well in Norway. The couple found useful material in archives, museums, private hands, and at the Danish Meteorological Institute in Copenhagen. “Many of the people we contacted were surprised someone was interested in this rather obscure subject of weather kite stations,” says Frank. “At Viborg, we discovered two houses that had been used by weather staff, then when vacated were converted to family homes. We were able to interview the families living there now and tell them of this interesting past.”

Says Dorte: “We met fascinating people, made an opening into unknown cultures, uncovered a lot of interesting interrelationships. It’s been fun. We’re sticking with our project for the foreseeable future.”