Ali Fujino

From Discourse 17

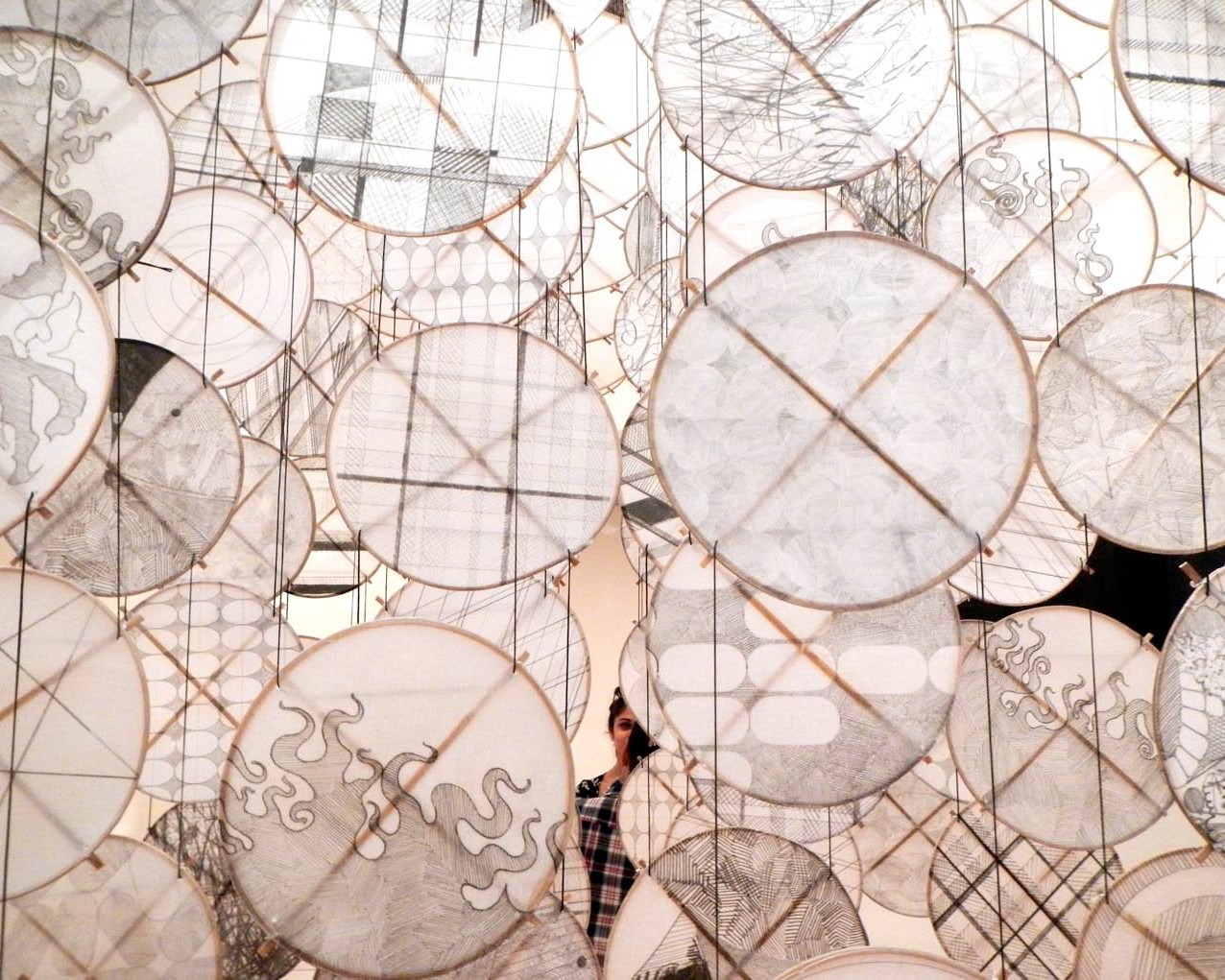

George Peters. Jacob Hashimoto’s “Gas Giant” installation at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.The pieces had subtle kinetic movement from air currents of the museum space.

There has always been a Hashimoto in my life. My first pull of air was in the arms of a Hashimoto, the famed Dr. Edward Hashimoto of University of Utah, who brought me and my entire Utah family into the world. Since then, I can track Hashimotos (artists, kitemakers, writers, scientists) popping up through my long list of life experiences – this list ends with the most recent, Jacob Hashimoto.

I can easily remember my first encounter with this Hashimoto. It wasn’t with the person, but a piece of his work that was installed in the ceiling of the Tacoma Art Museum Café. Not to be missed as one waited for their meal, I was entertained by the subtle movement of many small, square, individually-hung objects filling the entire ceiling. The effect was amazing, and even after my meal and visit to the museum, that was the single item that I walked away remembering.

It was Seattle kite artist Greg Kono who gave me a little intel on the piece and artist: “Oh man, you saw Jacob Hashimoto’s piece.”

Now I had his name. This was in 2003. The research began. I checked the Internet and found various articles and mention of his past and recent works.

Those little kite-like objects were a central theme to his art. He had not just made thousands of them to do single pieces, but over his years he was comfortable experimenting and creating tens of thousands of them. The collage effect was monumental. He was not afraid of size. The pieces grew in configuration and overall presentation. His name was showing up in many places, not just Tacoma, but in New York and Italy to name a few.

I would see mention in various respectable art publications and clip them to carefully

study them and share with others. Scott Skinner, Greg, and I became an unofficial Jacob Hashimoto fan club. We loved his visions and energy. But none of us had seen a real piece since Tacoma, in the 2000s.

We were due.

My most recent encounter with Jacob’s work was less than three months ago, at MOCA Pacific Design Center in Los Angeles. A few select old guard kitemakers and fliers have come to a kite gathering each year in Santa Monica, California. This core group are mainly artists, their media that of kites. We always have time to wander about the city, and one of us will suggest an artful activity for the day. This year it was unanimous: we would go see Jacob Hashimoto’s “ Gas Giant,” a superabundant atmosphere!

I wondered how did these kites become Jacob’s medium in the first place? Was he not a kitemaker and flier? I read that he studied painting and printmaking in college. During the summers he was a studio assistant to the Japanese artist Keiko Hara (www.keikohara.com). She worked with Japanese woodblock printing, which required much knowledge about paper. In Jacob’s work, he learned the same appreciation.

In his last year at the Chicago Art Institute, Jacob had trouble figuring out what to create. It was his father who suggested that, being in his studio, he would find something there. It could be anything, “Model airplanes or building kites…” The kites resonated with him, as he remembered watching his father build them when he was small – tiny kites that would fly out of his office window – and books that were around the house about kites. (His grandfather built kites too.) That year in Chicago, he started to build kites and take them to the park to fly. There was that magical moment. He wasn’t very good at making them, but he kept at it. He realized that year he needed to be making some paintings for the end of semester critiques. So he strung pieces of wire diagonally across the studio and hooked the kites on them with paper clips, to clear the wall for his paintings. He realized, “I could do everything I want to do with painting, but with these kites…” There was the “aha” moment.

George Peters. The forty foot ceiling suspended with a dizzying array of kite-like forms.

George Peters. Colorful patterned pieces are mixed into the white cloud array.

Ali Fujino. The lower gallery featured black and white kite forms installed from the ceiling space.

Ali Fujino. The lower gallery featured black and white kite forms installed from the ceiling space.

The installation at MOCA Pacific was one of the many variations of Jacob’s kite-like models, thousands of small kite shapes of various color, shape, and hanging lines. In each of his installations, he takes a core set of kite shapes and arranges them in configurations of space, light, and shapes. Starting in 1996, he built the first of his kite shapes and staged a small installation in his attic apartment in northwest Chicago. This installation was built over the course of a year and consisted of 1,000 handmade rectangular kites with a little cloud print on them. Later, these 1,000 pieces were installed in the back gallery of Ann Nathan Gallery in Chicago to photograph and de- install before the gallery opened for business.

She suggested it be left up for a few days to see how people reacted. It was seen by the chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and presently a larger version of the project was created with 10,000 elements.

From Chicago, a portion of the show went to Los Angeles, and later an installation of pieces was sent to Verona, Italy for the first show at Studio la Citta. Much later, another portion was sent back to Los Angeles. Known for painting, Jacob now had to move to a new media. Making multiples pointed him to printmaking. The kite-based figures allowed him to shift the picture plane from the wall to the architecture of the gallery or installation space.

I want to note that Jacob’s work did not start and stop with kite-like objects. The central part of his discoveries was architectural space and objects in that space, how they could change and how he could influence what was happening in a defined space. But be it known much of his fascination with the kite is that of youthful play and a Japanese-American heritage. Combining this with architectural spaces, he found a platform to work.

L.A.’s installation is a perfect example of his direction. This two-story space was gloriously filled with thousands of those kite-like objects. Recognizable were Chinese Beijing swallows, Japanese dakos, rokkakus, traditional American Eddy’s, hexagons, squares, diamonds, rounds, and ovals.

Some are stark white and others majestically multicolored with ornate designs. They repeat in color and printed patterns, giving him more than “shapes” to design. Sometimes the designs are hand painted, laminated paper, or printed multiples. Jacob is not afraid of color and complexity, some of the pattern work is extremely complicated, using several colors and several painted/printed shapes.

I was told the installation took four people about three full days. Most of the objects are hung individually, having their own line which goes from the kite shape to the ceiling. If you have 10,000 kite objects, there could easily be 10,000 hanging lines.

In an article in a very avant garde magazine, Elephant (Frame Publishers, #11/Summer 2012, pages 148-153), I read more about Jacob’s process of making thousands of kite- like objects.

George Peters. Close up of circular kite shapes with drawing patterns.

George Peters. Paper, bamboo, and string kite forms suspended from the ceiling create a cloud effect overhead.

He makes many of the items in his Brooklyn studio. The ovals and circles are heat-formed out of frames purchased from a company in Weifang, China. Circular shapes take Jacob and his crew about 15 minutes each, hexagon shapes maybe three minutes. Extensive testing of the frames was done to see what would happen to the frames over a long period of time in ultraviolet or sun light. These kite-like objects would be subject to light in his installations, warping and fading over time. Although well designed and engineered, there is really no way to preserve the original forms of any of the pieces.

The paper work is all done by Jacob and his crew in the studio. In this way, he controls the design work and the high caliber of craftsmanship for each item.

As a person who spent 20 plus years studying and documenting tethered flight (that which flies), I laugh at myself as I finish this article on Jacob and his kites. They are kite-like, and although they do not fly outdoors, who is to say they don’t fly? These kites move. It is an absolute delight to experience his installations and watch them move – in their own flight, a natural kineticism that is very poetic. It isn’t contrived at all. It’s flight. ◆

“GAS GIANT” VIDEOS

http://youtu.be/3SSys9OPU1U http://youtu.be/wOQP81ozHW4

JACOB’S BIO

Jacob Hashimoto www.jacobhashimoto.com

- Born in Greeley, Colorado, 1973

- Lives in New York City

- Carleton College (Northfield, MN), 1993

- BFA, School of the Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago, IL), 1996

- Has exhibited throughout the world