Maria Elena García Autino

Discourse-Issue-22

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. The Arch of Eddys, the first BaToCo group project.

“Thinking is the recognition of my ideas from the response of others.” – Alexander Kluge

What does a happy child on top of a mountain at the Argentinian Patagonia have in common with a group of youngsters living in poor conditions but enjoying a beautiful experience at the delta of the Rio de la Plata River in Buenos Aires? And with many other children all over Argentina, Chile, Guatemala, China, and Italy? Or with a grandfather who inhabits the joyful space of a gathering with his grandson?

All of them in some way or another participate in a creative public context of innovation and enjoyment rooted in the experience of a group of people. And I would like to describe this daring, meaningful experience of creation, encounter, and communication developed by artists, hobbyists, and enthusiasts of BaToCo (”Barriletes a Todo Costa” or “Kites at All Costs”), a group that was originally created by friends sharing a common hobby and is steadily enriched with new people, new ideas, new techniques.

I aim to emphasize the importance of a “context of participation” that transcends the activity of a human group and advances on the public sphere, enhancing it. I find the experience of Ba To Co illustrative of contemporary philosopher Alexander Kluge’s concept of “public sphere.”

Collective construction of large kites is not a BaToCo original or exclusive experience. It has been attempted and carried out by many others, in diverse parts of the world and at different times throughout history. The magnificent kite festival at Sumpango, Guatemala, with many teams working on the colorful kites, or the Bali Kite Festival, a seasonal religious festival, are good examples.

It should be noted that these experiences far transcend the mere creation of a beautiful object, but are essentially gatherings, a spontaneous association that emerges and expands between people who keep very special ties with each other. This collective experience is much richer than any individual or personal intention and generates an activity that transforms the context. It is the labor itself that establishes bonds that are not only interpersonal or limited to the here and now.

Each group kite is not only a piece put together with the participation of members of BaToCo and community but also represents the individual construction of multiple parts of a whole, creating a space for collective fun, where casual viewers passing by get involved to their surprise and curiosity.

All throughout the world, kites are usually built individually, though often collective experiences are had at festivals, tournaments, and competitions. In some cases, the kite construction itself is a cooperative effort that brings people together around a traditional event, acquiring social significance as an expression of protest, safeguarding ancestral cultural values on a manifestation of shared concern.

BaToCo has developed several group projects, whose progress can be appreciated on their website: www.BaToCo.org.

They probably originally arose from a playful experience among a small group of friends who met almost by chance a Sunday some years ago by the coast near the river. The encounter was casual and disorganized, with no other purpose than the fun and excitement of sharing those kites, surely crafted in traditional models to start with. They met almost exclusively to play together, with no purpose or reason other than to enjoy a beautiful object and a friendly gathering.

Victor Derka, one of the first BaToCo members, says: “There is no reliable record of the year BaToCo started as a group. In the years 1996 to 1998, builders had already been flying their first models on the coast of Vicente Lopez district, near the river. What characterized the group from the beginning was the free decision to enjoy the river, the get-together, and the first models that were, perhaps, rokakus. In 1998, the acronym BaToCo emerged.”

Almost unwittingly, they were creating a “public space” for participation, with huge prospects. In fact, that space, that invaluable encounter and communication, continues to grow today, incorporating new people, new ways to create and build, new experiences that expand participation.

In his essay “What Is Orientation in Thinking?”, as mentioned by Alexander Kluge, Immanuel Kant writes, “…how much and how correctly would we think if we did not communicate with others to whom we communicate our thoughts, and who communicate theirs with us!”

There are many and varied collective actions of social and community impact that in one way or another share the spirit of the batoqueros (BaToCo members) and are closely linked to it. Members never neglect to help even the most inexperienced build kites. They guide interested people personally or through worldwide forums.

Collective action generates other actions that expand the public space. This experience reminds me of the minkas or mingas, an ancient Latin American tradition. The minka or minga is a “collective work done for the community,” a pre-Columbian tradition of voluntary community work currently in use in several Latin American countries. This spirit is present, though not explicit, in the collective actions of the BaToCo group.

Perhaps the most important part of the experience of design and construction is what happens in the periphery of this center of intense creativity. Through its members, all outstanding builders, the experience expands to working groups in schools, hospitals, and community centers across the country. It generates new creative contexts and other public spaces of participation, which in turn also spread out. It generates links with the visual arts, literature, science, and with new magical universes never imagined before.

Therein lies the strength and the extraordinary power of collective epicenters, constituting significant differences between “being alone” and “not being alone.” As Alexander Kluge says, “Working, living, and loving in isolation as a hermit does not involve a civilizing opportunity.”

We are facing a situation of contemporary global crisis. Times of crisis discover potentials and generate collective action. This has been happening almost inadvertently in many groups in Argentina. BaToCo is one of them.

It is impossible not to wonder what has brought together the members of this unique group over all these years. It is the instinctive trust that, from the beginning, consolidated confidence in the skill, knowledge, and technique of each other. This confidence has been strengthened over the years, leading every collective proposal to success. They are artists when they perform their individual creations, and even more artists when bonded on a collective action.

Collective creation, though it leads to the construction of a playful object, is much more than mere entertainment. Entertainment is befogging. Creation opens a window to new horizons. Those big kites are see-through objects that do not end in themselves but open up unexpected possibilities.

In the shared BaToCo spirit, building a beautiful object together implies the collective construction of joy, maybe the best construction that a human group can accomplish.

Annually, members of BaToCo propose a kite construction project that will result in the joint work of the group.

THE ARCH OF EDDYS

This was the first group construction work achieved by members of BaToCo. The arch is 140 meters long and it frames all the encounters, welcoming artists and spectators to join BaToCo flights.

This project did not attempt to create an original design for each kite. A conventional Eddy model was chosen, but t he participation of every one of the group members gave a personal “touch” to each kite. It represents individuality when all its members gather to fly it.

This work participated in various kite festivals: the Festival of Rosario, the International Festival of Bogota, and the Buenos Aires Wind Festival each year.

GREAT SOUTHERN DRAGON

For the Festival of Rosario in 2003, BaToCo members decided to create a yearly new group construction project.

The idea to build this great flying giant was an attempt to reinforce the cohesion of the group and individual participation in a collective construction enjoyed by everyone. The result is a beautiful and huge flying machine that now crosses our sky. It has a majestic flight, and no one is indifferent to its presence in the sky.

PULPERÍA

Pulpería was a group BaToCo workshop that aimed to construct dozens of inflatable octopus kites, following Colombian kite builder Alejandro Uribe’s original pattern. (Pulpería is an expression that refers to a large group of octopi and also to a traditional rural pub or grocery store where country people used to meet.)

The octopi are inflatable kites 11 meters long, built of polyethylene and bound with tape. They have no rigid component in their structure and therefore are held only by the air inside them.

The octopi were flown on the Paseo de la Costa, the favorite place in Buenos Aires for BaToCo members to fly their crafts. Neither the fog nor the cold could stop this project. It was anticipated with great eagerness – dozens of octopi flying with their tentacles writhing in the air!

Lucky spectators passing by were amazed at this “phenomenon.” This workshop made clear the strength of the group.

LA BANDEROLA (THE BIG FLAG)

In 2005, BaToCo began a group project that aimed to carry out a giant kite, “La Banderola” (The Big Flag).

The great achievement of the project was to bring together all its members on a shared activity demanding effort, enthusiasm, and creativity. This project was noteworthy because many sectors of the community were involved on the design of the panels which, when combined, formed a huge Argentinian flag. BaToCo members, individual artists, schools, hospitals, community institutions – all worked hard to make each section of this giant kite.

Each one of the participants worked in their specific field individually or with the group they chose. Each panel also brought about group work that was later integrated with the final result, creating a kind of working fractal pattern that opened new and interesting perspectives.

Some of the panel designs by Roberto Fontanarrosa and other Argentine artists were reproduced to give the Banderola a national touch, representing our country all over the world.

BICENTENNIAL ROSETTE

The 2011 group project involved the construction of a kite baptized by BaToCo members as “Bicentennial Rosette.” It has the characteristics of a foil with circular shape. The model stands for the national symbol escarapela (rosette), and it was selected for the Argentine Bicentennial celebration.

THE SURUBÍ: THE LATEST GROUP PROJECT

The idea arose several years ago to make a giant, inflatable kite recreating a distinctive Argentine animal. The group finally chose the surubí and created a kite about 20 meters long and 7.6 meters wide. The surubí is a South American catfish whose population has declined significantly since the last decades of the twentieth century due to overfishing and dam building.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Great Southern Dragon kite.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Great Southern Dragon kite.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Pulpería, dozens of octopus kites.

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s Pulpería, dozens of octopus kites.

The surubí form allows us to make an inflatable that flies alone or with minimal help from a pilot. It is very suitable because it has a wide mouth and the body is quite flat, which gives a good surface for it to rise with the wind.

Various decorative patterns were proposed and drawn. The first ones seemed colorful but also very complicated and time- consuming. So the project lay in a drawer for nearly two years. During this time the group completed the “Rosette” and implemented several more workshops.

In 2014, some members of BaToCo insisted on resuming the project and decided to simplify the design using diamonds of alternating colors ranging from yellow to blue and shaping the body accordingly. This design greatly facilitates the construction because the boxes are all the same, just the color changes on each. When everything was simplified, the scheme was completed by cutting more than 600 pieces of fabric!

After building a quick test on polyethylene fixed with tape (a technique learned from kite builder Alejandro Uribe) to ensure evidence of relatively good flying, the sequence was more or less the usual one on BaToCo group projects:

- Decide on a computer design model and surface decoration.

- Investigate the availability of materials.

- Set up measurements.

- Print/plot molds or patterns in real size.

- Print the general scheme.

- Assemble sequence/joining of parts.

- Select and draw parts over the fabrics.

- Number the pieces and coordinate the hard work of cutting them. Organize the delicate and laborious construction.

- Join the parts, place reinforcements, and laboriously attain the desired shape, a task distributed among participants in successive meetings.

- Assemble the parts: first the set of pieces that make up the top of the fish, then the bottom. Once completed, the joints are reinforced with internal threads.

- Assemble the bottom to the top. The giant begins to appear. Fins are attached.

- Build the network of internal threads that fit the flattened shape of the body.

- Reinforce all joints. Place mustaches.

- Place threads and flanges.

- Inflate the Surubí with a blower to see the overall shape and volume.

- Perform a flight test.

The big size is an additional difficulty. To have a computer complete design helps organize the job.

Another challenge is to coordinate tasks in each workshop with usually between 10 and 15 builders. It is necessary to properly distribute the activities, so that the participants do not get bored and everyone feels involved in working and progressing the sequence. Groups of 2/3/4 people are structured to carry out a specific activity: cutting the fabric, helping with everything, classifying and sewing the parts, taking note of what has been done according to scheme.

Of course, there are primary enforcement activities (cutting, measuring, sewing, joining, controlling, scoring) and support activities (sorting, coordinating the lunch or snack, drinking mate, a caffeine-rich infused drink, calculating adequacy of materials, cleaning, sorting). Spontaneous activities like jokes, discussions, some gossip, planning future purchases, sharing festival photos, and travel planning are included.

Note: The Surubí is in full construction. It will probably be finished in February and first flown in March 2016, after sewing the flaps, joining the whole body, testing it in flight, and adjusting everything.

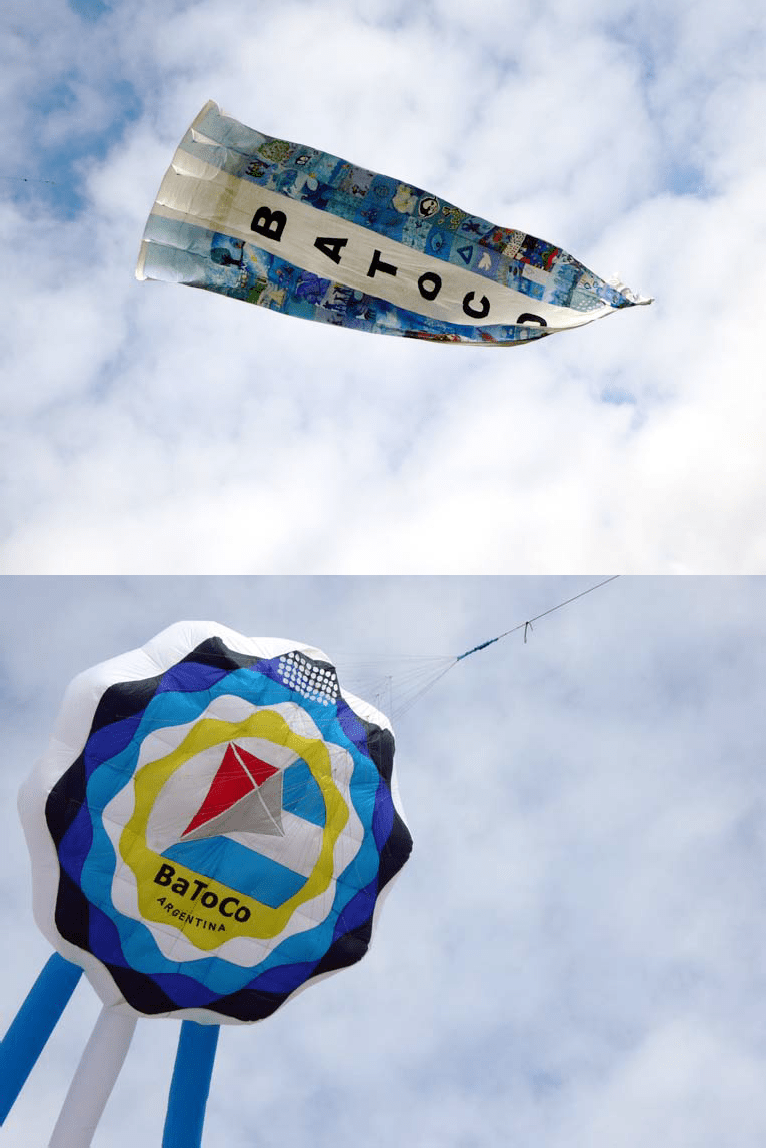

Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka. BaToCo’s “La Banderola” (The Big Flag), top, and Bicentennial Rosette, bottom.

BaToCo Group. BaToCo’s latest project, the Surubí fish kite, just completed.

Photos and videos of the group projects, the construction processes, and the final results can be found on the BaToCo website at: www.BaToCo.org/barriletes/trabajo_grupal/

So far, says Pablo Macchiavello, one of the leaders of this task, “I think it’s one of the most industrious group works we have done; we all hope to see it flying. This wonderful kite is emerging from the love we all have in our group for the kites and BaToCo.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is essential to include a reference to the ideas of contemporary philosopher Alexander Kluge. I feel indebted. I admired them on Kluge films on German television and in his books and lectures. To apply his ideas means to develop his powerful concept of “public sphere” and confirm its accuracy.

The details of the construction process and information on group experiences were provided by Gustavo Sonzogni, Pablo Macchiavello, and Victor Derka.

Each and every one of BaToCo’s followers have contributed directly or indirectly to this article. The ideas, enthusiasm, and love belongs to all members. Thanks to all of them. ◆