Bob Moore

From Discourse 18

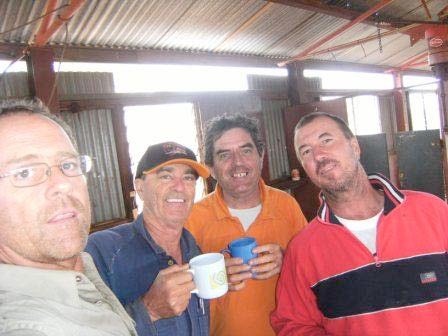

Bob Moore. From left to right, Bob Moore, Roger Martin, Michael Jenkins, and Michael Richards after their 2014 record kite flight to 16,038 feet.

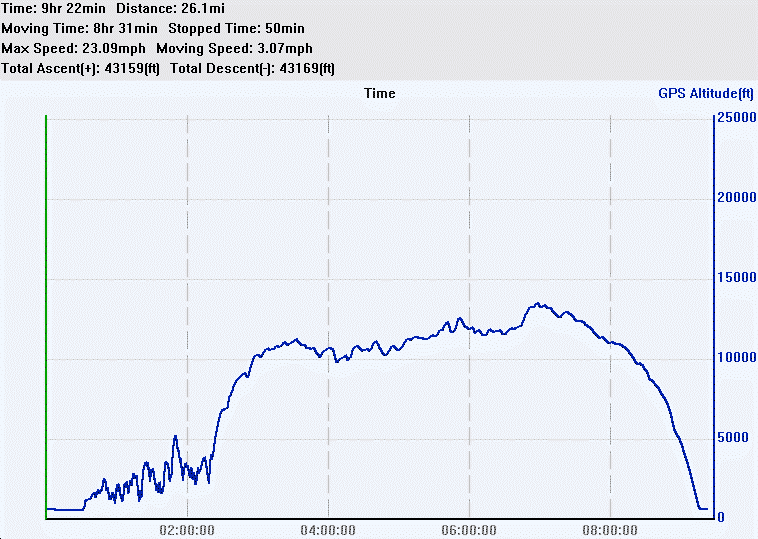

Bob Moore. A GPS log of the flight.

On September 23rd, 2014, four Australian kite enthusiasts flew a kite to a claimed 16,038 feet above the launch point at an airfield on a 50,000-acre sheep farm called Cable Downs, in Western NSW, Australia. This was the venue for all our record attempts over the last ten years. It is a site remote from our homes in Sydney, 750 kilometers (466 miles) to the east of this dry and dusty place.

We have made this annual trek to Cable Downs in seven of the last ten years. There have been a number of other people involved, but the current team has been together for the last five attempts.

Mike Richards is well known in the eastern suburbs of Sydney as the kite man and runs a diverse business selling, building, and repairing kites. He is a jack of all trades but it’s his expert kite building and flying skills that have had an enormous benefit to our high flying aspirations. The kites were conceived and designed by me, but Michael took my sketches and added his own ideas to make these kites powerful, stable, robust, and very impressive fliers.

Mike Jenkins is a neighbor of Mike Richards. I met him at the Bondi Festival of the Winds in 2005. I felt an immediate rapport with him. He is a down-to-earth, intelligent man with great kite designing, building, and flying skills. He has won numerous awards with his kites at Festival of the Winds. He is a competition sailor, and it is this experience that makes him an excellent choice for a high altitude kite flying team. His “no bull” approach also keeps me focused and grounded.

Roger Martin is a talented kite builder and flier who also lives close to Mike Richard’s kite shop. He is an experienced photographer, which has great benefit to our campaign for the world altitude record. He frequently accompanies Mike Richards to help with large kite displays at festivals around Australia and South East Asia. His maturity, experience, and good sense of humor are a great asset to our team.

It’s not just the buzz of big kite flying that is the attraction to our record attempts; it’s the camaraderie and mateship that attracts me to drive 1,500 kilometers (932 miles) roundtrip to this remote place. We have fun in our one-star hotel, the wool shed, a rough ironclad out-building, the habitat of tough shearers who clip the wool off thousands of sheep in an annual ritual. The place has a liberal coating of lanolin from the tons of wool shorn from the sheep’s backs over the last 50 or so years. A mild odor of sheep dung permeates the air, but we get use to it. We eat surprisingly well with Mike Jenkins’ culinary skills appreciated. In the evenings we drink beer and wine, talk rubbish, and watch some movies projected onto a big screen made of Tyvec. We play cards and laugh a lot. Then we sleep well and dream of perfect winds and floating like an eagle thousands of feet above the airstrip.

We are a cohesive, happy, and effective team. This is an important factor in our record breaking flight this year and all our high flights over the last ten years. We enjoy being together and we enjoy the challenge of high altitude kite flying.

For all of our flights since 2005, we have used one kite design and size (apart from one flight in 2005 with a 170 square foot DT Delta). Our 120 square foot DT deltas have been an effective high flying tool. They have proved robust, resilient, and capable fliers. We were confident of these kites breaking the altitude record, but, as with any kite, the right wind conditions are essential. There are other designs that are potential candidates, but we couldn’t trial them all. The DT delta is very strong, easy to transport, and on field assembly is a two minute task. I would have liked to use a Hargraves box kite, but the ripstop and fiberglass tube versions I built were difficult to construct and tune for high altitude flight.

We noticed that the 120 square foot DT Delta had reached its upper wind limit at about 30 knots and was becoming a less efficient flier for every knot above 20. The maximum line tension generated was 130 pounds, and by then the kite’s drag was dominating the lift. We discussed how we might increase the wind range of the kite, thereby improving the kite’s lift. A simple but effective way may be to fit a second spreader. I had experimented with a double spreader on a larger version of these kites in 2005, but came to no conclusion if it would be effective on the 120 square foot kite. We kept the idea in the back of our minds.

On Monday, September 22nd, 2014, we made our first altitude record attempt since late September 2012. I arrived late on Saturday, September 21st, a day before my teammates who arrived late on Sunday. I had done most of the preliminary set up, but on Monday the 22nd it took another two hours to ready the kite, line, and other paraphernalia that make up our base station and recording equipment. Setting up the flight must be meticulous. One error can see the kite drifting off, never to be seen again, or the GPS telemetry not recording the flight.

The ground wind was ideal, with a steady 10-12 knot wind blowing straight down the airstrip from east northeast. We launched the kite on 300 meters of line at about 10am. It climbed steadily to 6,000 feet. Then there were several periods of altitude loss and see-sawing of the kite with winch reversal, trying to work the kite up higher.

The Doug La Rock tension gauge (pictured on page 19) is an essential tool for deciding when and how quickly to winch line out. In conjunction with the GPS telemetry information displayed on the computer screen, this means we don’t need to see the kite to picture what it is doing. Without these things we would be blind.

The computer observer calls out the altitude and informs whether the kite is rising or falling so the winch operator reels line in, lets line out, or pauses the winch. The line payout controller is influenced by line tension as well. The greater the wind, the higher the line tension and the faster the line release. There is a surprising degree of control over the kite’s movement, although it can only be away, toward, and up and down, not side to side, as this is controlled by wind direction at the kite.

The kite stalled when it reached about 12,500 feet, and we spent another hour working the winch to make little progress, with the maximum at 12,778 feet above our launch point – a decent altitude in anyone’s language, but well short of our target of 15,000 feet. We ran out of time to work the kite any higher, as we are limited by the Civil Aviation Safety Authority agreement to have the kite landed before last light. We landed the kite around 6pm with about an hour of light left. We packed up and headed back to the wool shed. While winching the line in, we analyzed the flight and came to the conclusion that there may have been enough wind to reach 15,000 feet if the kite had had more lift.

We had discussed fitting a double spreader in 2012 and now was the time to try it. Mike Richards and Mike Jenkins busied themselves at first light the next morning fabricating and fitting the second spreader. We carry spares of everything, so it was no problem to make up and fit another 15mm fiberglass spreader and the rubber sleeves which attach them to the wing spars. For those not familiar with deltas, the spreader is the horizontal spar at the rear of the kite that holds the wings open. With one spreader, the wings folded inward at high wind speeds in excess of 20 knots. It is necessary for a delta to have flexible spars, but if they are too stiff the kite will be nervous, unstable, and even crash-prone.

On day two, we got an earlier start, as we already had the equipment set up from the day before. The kite was launched by about 9am. I had contacted Air Services earlier to open the zone for us and close it to air traffic. The generator – the lifeline to all our electronics, winch, and coffee machine – had its fuel checked and topped up. (It needs to run for up to 12 hours each day. We have no backup generator, so it just has chug away in the background.)

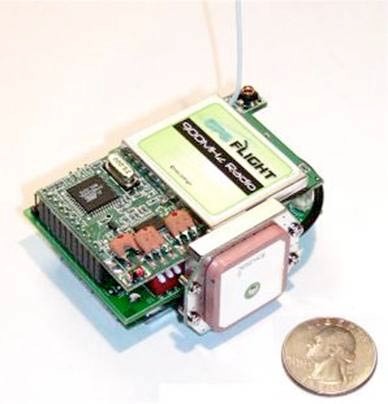

The GPSFlight telemetry unit with its alkaline battery pack was inserted into its pouch at the back of the kite. (It had provided enough charge to keep the data transmitting for 54 hours in midwinter testing in my backyard at home in Baulkham Hills.) The Holux data logger was on board as our GPS data backup. The Holux GPS data logger’s batteries last 12 hours, but this is at the very limit of our daylight window. The laptop was on with the GPS Dash software indicating valid satellite locks from the onboard GPS receiver, and the telltale flashing light on the radio telemetry receiver was blinking like a heartbeat monitor. If it stops, the flight is virtually dead, as without it we are flying blind. A file is opened on the telemetry software to record the data. This is a small but vital step. Without the telemetry log, we have only half the evidence that form the primary source of positional and altitude data. The telemetry software is set to ground level, so that the GPS sends data via the radio signal for decoding and displays altitude above our launch point. There are ten other pieces of information that are transmitted, including the core data set that forms the NMEA standard for GPS receivers.

Bob Moore. The wool shed (”our one-star hotel”) is very basic but has plenty of character.

Bob Moore. Mike Richards, Roger Martin, Bob Moore, and Michael Jenkins, “a cohesive, happy, and effective team.”

Bob Moore

Bob Moore. The hub of the record attempts. Inside is the computer- controlled winch, generator, 25,000 meters of Dyneema line, and other kite paraphernalia. We carry three spare of everything, except the generator and winch.

Bob Moore. The tension gauge is an “essential tool” for deciding when and how quickly to winch line out.

This tiny GPS unit is the “vital heartbeat” of the record attempt.

The laptop computer started on the small table outside Mike’s truck, but later was transferred to the front seat to improve the view of the screen which was being obscured by glare. Roger sat in the passenger seat of the truck with the computer on his lap.

The two Mikes walked the kite out with the winch in reverse, paying out line. They carry a walkie-talkie to time the release with the winch controller. No line reversal was needed, as the wind was strong enough to power the kite rapidly to 500 feet. The ground wind was a couple of knots stronger than the day before. The winch was locked with the big disk brake, a new addition to the winch system. It worked great with fingertip control of line out. With a double spreader and a 12-15 knot wind, the kite pulled like a bull in spring, rising at a high angle and taking line at a rapid rate.

There were about 3/8ths of cumulous cloud cover at an estimated 6,000 to 7,000 feet. There was patchy high cloud at about 14,000 feet, but that was coming and going as the day progressed. We were over the lower cloud in about 40 minutes. From then on, the kite was either obscured by cloud or too high to locate easily with binoculars and a powerful telescope. The kite was past 10,000 feet within 1 hour, 15 minutes. This compares to 8-10 ten hours for other flights to this altitude. The line tension was stable and rising from 40 pounds to 80 pounds. The rate of climb slowed a little between 10,000 and 12,000 feet, but all the time we were releasing line under brake control, as the kite was providing sufficient line torque to overcome winch inertia and friction. We didn’t have to push line out with the winch motor at all. It was a steady climb past the Synergy record altitude of 14,609 feet and only paused at 15,500 feet.

We had run out of line with only about 200 meters left on the reel and 12,620 meters up in the sky. We waited for an hour, in which time the kite gradually rose to a maximum of 16,038 feet above the launch point, and the tension gauge was hovering between 110 and 120 pounds. It was porpoising for half an hour when we decided that 16,000 feet was high enough. We may have been able to go higher with more line, but we were happy with what we had achieved.

An hour before the kite breached the record altitude, we sent the farmer’s son up to fetch his parents to witness our record achievement. They were as excited as us because they have hosted our record attempts for ten years. They rode the ups and downs with us, although I never managed to convert them to the kiting religion. They understood what we were doing and never had to ask why. It was also their last day as custodians of Cable Downs. They were moving to another farm 800 kilometers (497 miles) to the south.

We all jumped for joy, but despite the excitement of breaking the record, the implications had yet to sink in, which would take weeks. It was clear that adding a second spreader was the main contributing factor to our outstanding altitude with a relatively small kite. We cannot discount the contribution of slightly stronger winds, but these winds also meant higher line drag.

The line angle was at about 15 degrees and the kite angle about 24 degrees. Adding more line may have increased the altitude by 1,000 feet, but I suspected I would run out of time or the effort of adding another reel of line would not result in any height gain. 16,038 feet is a fine effort. Jesse Gersensen was the first to know of our record when he phoned our on-field phone from the Czech Republic. He is a high altitude enthusiast with a strong presence on the Kite Builders forum. He spread the news via this forum.

After nearly four hours of winching the line in, the kite landed around 5pm. After the retrieval was started and about a hour in, the GPS telemetry stopped transmitting. Later I saw that the transmitter aerial had worked its way loose, probably from the wing vibration from the flapping trailing edge. The trailing edge was tattered from the flogging of winds between 20 and 40 knots over eight hours. Fortunately, the telemetry data was recorded for 2/3 of the flight, with the maximum altitude included.

The Holux data logger recorded the whole flight. The GPSFlight and Holux data will be sent a long with other supporting information to the Australian Kiteflying Society and Guinness World Records. The GPS devices will be certified by qualified surveyors or engineers. We have been working to get to this altitude for ten years. My computer modeling and calculations supported my belief that this kite could do it. We had to have the right wind and the thinnest, strongest line. It seems like a simple task to build a big kite and, with a truckload of line, fly it very, very high. It has proved to be a devilishly elusive goal. I have focused on improving the equipment and methods each time we make an attempt, and it is this persistent, patient approach that has rewarded us in the end. If it had been easy and we had reached the record on day one in 2005, I think I would have been disappointed, and being so easy, many others would have upped the ante.

I have a number of sponsors, but most of the expense has been borne by me and Mike Richards. Because it is an amateur activity, it had to be managed within a limited budget and most things are homemade. We have, however, approached the altitude record attempts in a responsible and professional style, particularly working with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority.

Apart from Mike Richards, my most significant sponsor has been DSM Dyneema in Holland who, in conjunction with Cousin-Trestec in France, supplied over 33,000 meters of line. That would be equivalent to $15,000 of line retail. I don’t think my budget could have supported such an expenditure. I cannot ignore the smaller sponsors such as Lewis Pulleys and Universal Instruments.

I estimate the total cost of the kite record attempts to be in the order of $80,000, but from our perspective it has been worth every cent. To fund this hobby requires the support of my wife and the partners of the other team members. My wife is not a kite fan, but she takes photos at kite festivals and tolerates my long stints in the workshop and on the Kite Builders forum. She does get jealous of my high flying treks to Cable Downs sometimes but has a grudging admiration for our efforts, persistence, and the science that goes into our project. She sees the money going into our record attempts and, being a business-minded women, wonders “What is the point? Do you want to be famous? Do you make any money?” I just grin and shrug my shoulders and say, “I like it.”

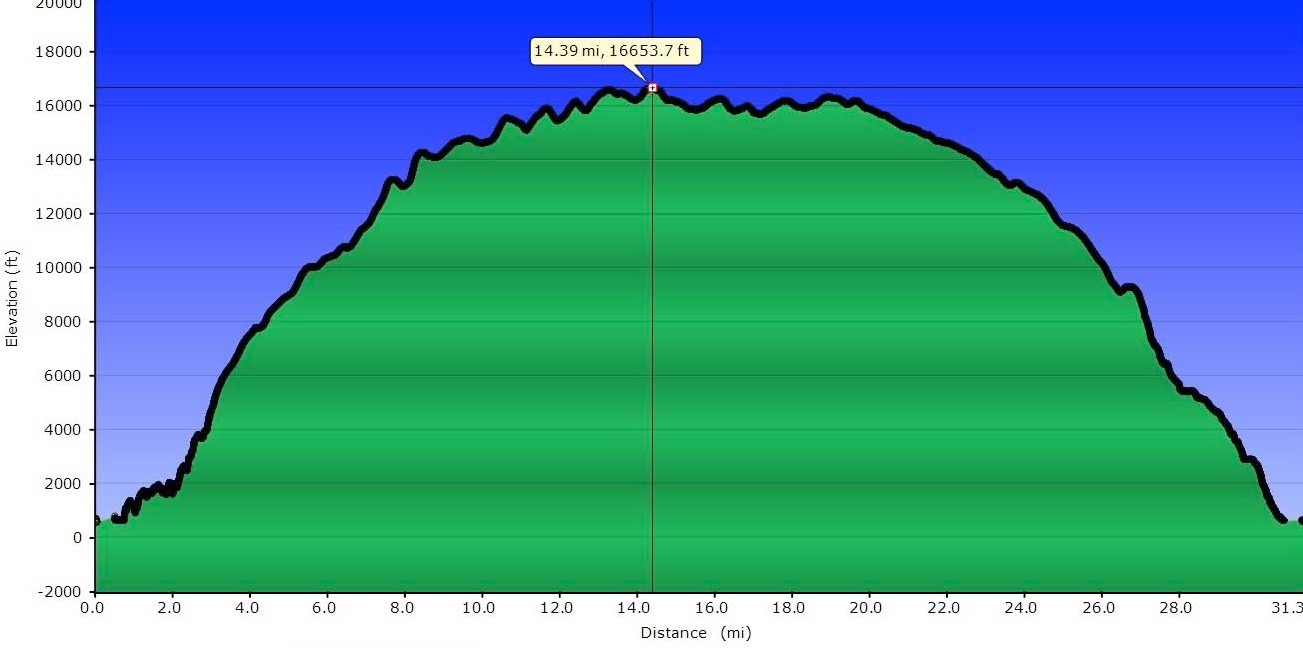

Bob Moore. The Holux GPS shows the kite reaching a height 15 feet lower than the GPSFlight unit.

Bob Moore. The Holux GPS log of the record kite flight displayed in Garmin Map Source.

We packed things into the trailer, but as we planned to do some onboard photography the following day, we didn’t pack too securely.

We debriefed over a few wines that evening, and I examined the GPS logs. Both confirmed that the kite had reached over 16,000 feet above ground level. In addition to the GPS data, we have 15-minute hand written logs of line out, line angle, altitude, and horizontal distance to the kite.

The acceptance of a particular altitude for the record will depend on GPS certification. The two systems varied by 15 feet for maximum altitude during the record flight. This is only a 0.08% variation. I expect the maximum error for either GPS unit to be in the order of 0.2% or 32 feet at the maximum height. If the error predictions are correct, then the record will still be over 16,000 feet above the ground. Generally, consumer-grade GPS units with DGPS augmentation are accurate to within 1 meter for position and 2 meters for altitude with more than 8 satellites in view. At the flying site, there were 11-13 satellites in view.

However, we must go through due process to get recognition for our altitude, and that takes time and thorough presentation of our observations and data.

Some interesting stats on the flight:

The GPS devices collected over 72,000 lines of data, and on each line was ten pieces of information including altitude above sea level, altitude above ground level, horizontal distance, horizontal speed, time, number of satellites acquired, positional error, battery, and a couple of others. That’s 720,000 pieces of separate information. For Richard Synergy’s flight of 2000, there were three pieces of information about altitude, ground height, and the maximum height shown by two hiking watches. Technology has come a long way in 14 years, but GPS devices were available then. Without GPS, I would use Barometric altimeters and a different method of ensuring accurate height data was attained.

12,600 meters of line had been loaded onto the storage reel. 12,620 meters was measured out by the payout gauge. 200 meters remained on the reel. So only 12,400 meters was used. Where did the other 220 meters come from? 1.7% line stretch.

The line is between 0.7 and 0.8 mm thick. Total line weight was about 7 kg.

The kite reached 10,000 feet in about 1 hour, 15 minutes.

Total flying time was just under 8 hours.

The kite was over 7 miles away from the launch point at maximum altitude.

The maximum speed of the kite was 26mph.

The total weight of the kite was 3,560 grams.

The minimum air temperature was an estimated -12 degrees Celsius at 16,000 feet, from Bureau of Meteorology forecasts.

The kite becomes increasingly difficult to view with the naked eye after 6,000 feet.

By 10,000 feet, it is even hard to locate with binoculars, unless you know exactly where to look.

The kite colors are somewhat arbitrary and depend on what stock of ripstop Mike Richards has in his shop.

We have two assembled kites and have two replacement skins with spare spars. We also have a carbon spar set for light wind conditions.

For measuring line angle, I use a slope gauge with spirit levels embedded.

The line payout meter is a distance wheel calibrated to measure line payout to 99.99% accuracy.

The line payout calibration is done with a digital cycle meter which is also used to measure line speed.

Jesse Gersensen estimated that if the winds on the lower half of the height profile weren’t so strong the kite would have exceeded 19,000 feet.

The following day, Wednesday, September 24th, the wind had intensified and storms were forecast around midday. We never contemplated upping the record, but we wanted to capture some onboard video and other images to add to our collection. Mike had put together a short video and stills to upload to YouTube on return to Sydney.

I would like to thank Mike Richards, Mike Jenkins, and Roger Martin for their support, skills, and work in preparing for our record attempts. I also thank Jesse Gersensen for taking the time to look up the wind predictions for our zone and for being a strong advocate for high altitude flight. Doug La Rock made the tension gauge for us and it is an invaluable tool. All the guys and girls on Kite Builders, including Cliff Quinn, Ron Bohart, TBHinPhilly, Aldenmiller, Pumpkin, Jeepster, Kite Guy, Turn 11, Sadsack, Quincy, Old Goat, MotoTrev, my AKS members, Linda Saunders, AKA area 13 rep, and a host of others.

My email has been swamped with congratulatory messages and requests for friendship on Facebook from the worldwide kiting community. I have had more people following my attempts than I realized. The verification process is underway, and I believe the evidence is so overwhelming that I can confidently claim a new world record altitude of at least 16,000 feet.

It’s back to reality, work, gardening, chores, and the daily grind of life in a big city. I know if I get stressed out I can go down to the park and fly a kite or I can sit in my workshop watching videos of the world record attempts.

Next we may attempt the absolute (kite train) record but I’d like to get the single line verification out of the way before I think seriously about another record campaign. I would be setting a target at about 40,000 feet, but this is a whole new, bigger ball game and would need sponsorship.

I hope I have established our credentials with our methods and open disclosure over the past ten years. ◆