FRIENDS IN THE FIELD: THE AMERICAN KITEFLIERS ASSOCIATION

Shelly Leavens

ar·chive (är’kīv’) n.

- A place or collection containing records, documents, or other materials of historical interest. 2. A repository for stored memories or information: the archive of the mind.

All definitions from dictionary.reference.com

PREFACE

In 1978 Bob Price of Maryland was appointed Chairman of the Archives Committee for the “new” AKA. For eighteen years he and his wife, Jewell, gathered and organized an incredible amount of material: news clippings and ads, membership and financial records, club newsletters, bylaws and meeting minutes, competition rules and awards, videos, correspondence from association presidents a n d c o m m i t t e e m e m b e r s , v a r i o u s memorabilia, and much more. During the summer of 1995, Price was ready to be relieved of the job, and the AKA began to look for a new home for the archives. First it was transferred to Drachen, and after holding it in Seattle for a year, the board of directors determined the World Kite Museum (WKM) in Long Beach, Washington was a better home for the collection. Five 4-drawer metal filing cabinets and 30 boxes of archives were shipped from Maryland and eventually found themselves tucked away in the backrooms of the WKM.

On a recent cloudy Tuesday, I decided to drive to the coast and pay a visit to WKM Director Kay Buesing in order to dig through all the things Price and the other leaders of AKA had decided to save. There is something special about the tactile nature of an archive. Yet, while museums and archives represent access and authority on our collective past, and as comprehensive or representational as they hope to be, museums and archives can really only offer a rather narrow lens. What is saved provides a constructed view of history, and for the AKA this is no different. The importance imbued in these remaining documents comes directly from those who saved them, and from what they did not or were not able to save. It is up to those who access this information to think about a past that is both documented and inferred. Now, with mass email and digital surrogates filling our servers, it’s hard to know what to save and what to toss. Regardless, what I found both surprised and delighted me, as well as made me thankful to all who had helped preserve the archive.

FRIENDS IN THE FIELD

The American Kitefliers Association (AKA) started in 1964 as one man in front of his typewriter, reflecting on the people and ideas of his beloved hobby – kites. Now a household name for American kiting, Bob Ingraham and a few other closet-kitefliers had been corresponding since the early 1960s, exchanging hand-drawn plans, kite tips, and generally taking part in each others’ lives with kites as the hub. The initial AKA was hatched as a movement, a strictly adult club, mostly men, who could finally feel free to be open about their love of kites and talk to each other about things like bridles and spars – things most non-kitefliers would relate to other sports entirely or call “kid’s stuff.” Now the largest kiting organization in the world, the AKA has come a long way, yet it still holds many of the same founding tenets of Ingraham’s vision.

pub·lish (pŭb’lĭsh) v.

1. To prepare and issue (printed material) for sale or distribution to the public. 2. To announce formally or officially; proclaim; promulgate. 3. To make publicly or generally known.

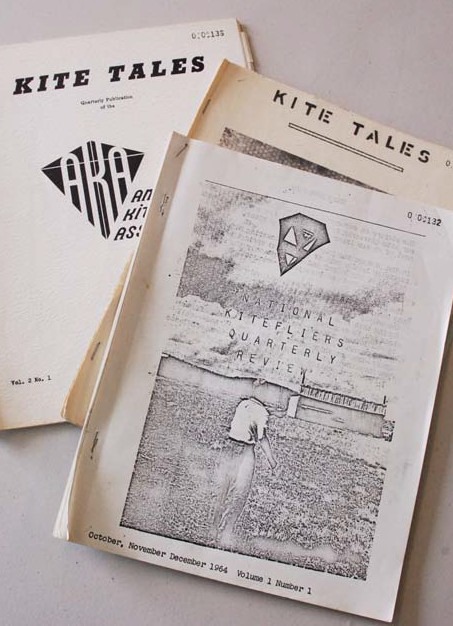

We have produced, at great considerable effort, 25 copies of this first quarterly,” wrote Ingraham in the Oct-Dec 1964 issue of his National Kitefliers Quarterly Review.

It was with sheer excitement I discovered the stack of Ingraham’s rare original publications tucked into the back of one of the filing cabinets filling a small room at WKM. I immediately read the first issue cover to cover, and through Ingraham’s words, literally re-lived the birth of the AKA. Throughout the entire issue, “The Editor,” as Ingraham calls himself, uses his dry humor to poke fun at the few fliers that have joined him in declaring the sport worthy of adult time and hard-earned money. For Ingraham, it had been a long time coming, and it was exposing a part of himself he had felt ashamed and alone with for some time. In every word he types, you can sense his excitement that finally he has found kinship, and the fledgling association he has privately nurtured is ready to take flight.

However, while it may have been Ingraham’s idea to form “this silly little club,” as he called it, he also noted that, “eight or nine members do not constitute a vast national organization of any group, no matter how dedicated… From now on each member is expected to contribute material. This is an order, not a request in any sense.” He needed help to really get it going, and to his delight, many soon found his enthusiasm and devotion infectious.

Among his original group of devotees were Tony “The Kite Man” Ziegler of Michigan, Will Yolen of New York City, Walter Scott and Benn Blinn, both of Ohio, Harry Sauls of California, and Francis Rogallo of North Carolina. “Having Fran in our club is sort of like having Michelangelo join your artist club,” he quips. “While we deeply appreciate his interest and knowledge about kites, we have no intention of exploiting or harassing him because of his position. We will only bother him with technical explanations of such things as: ‘Why do kites fly?’ Well, why do they Francis?” Sure enough, the next issue featured a reply from Rogallo, in all seriousness, answering just that question.

Shelly Leavens. It all started here: the first three issues of Bob Ingraham’s Kite Tales are mimeographed in 1964/65.

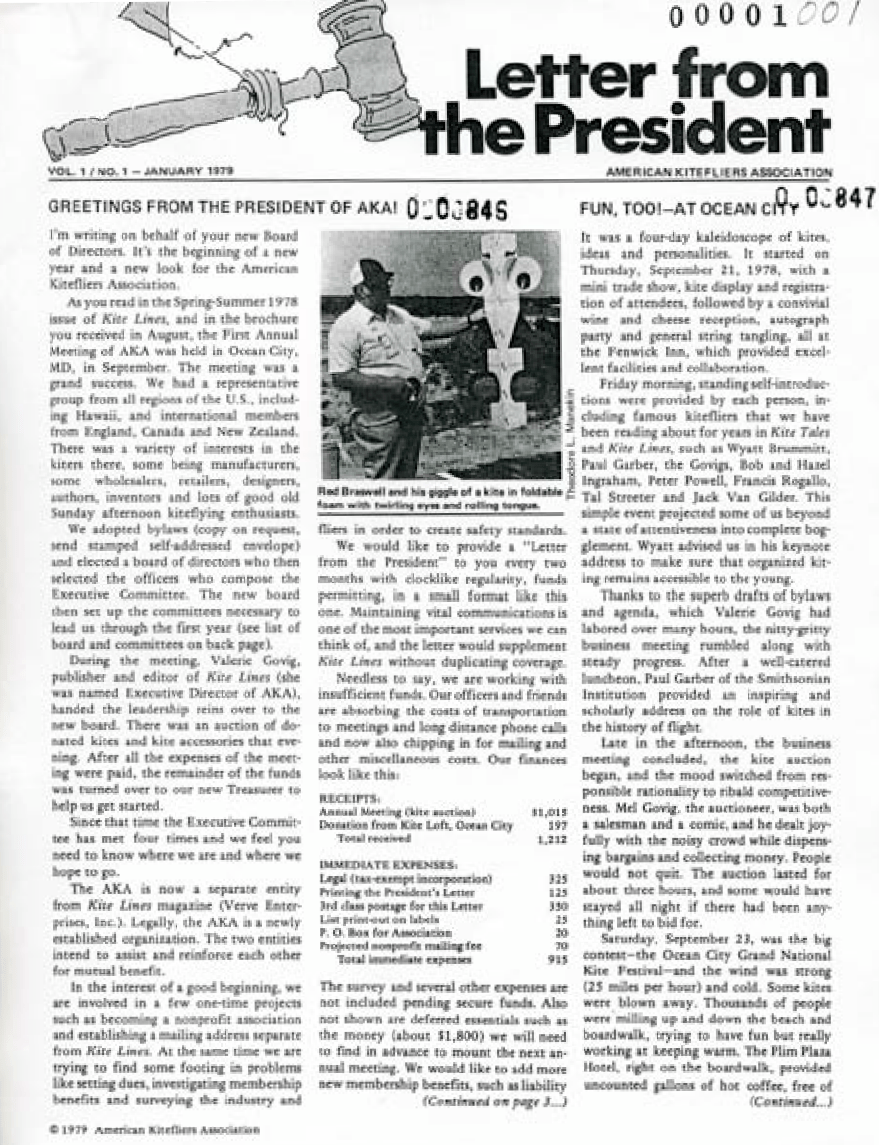

Shelly Leavens. AKA as a non-profit entity begins publishing Letter from the President in 1979.

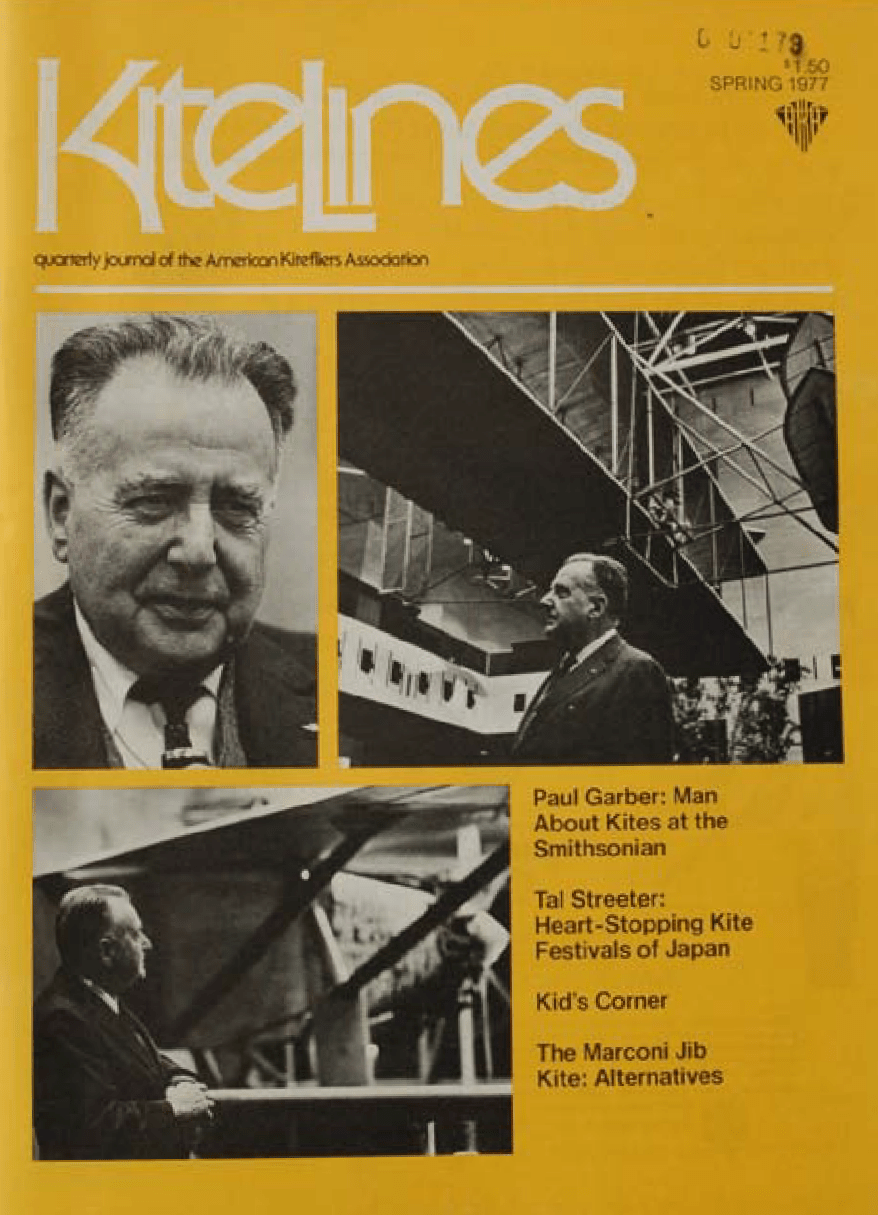

Shelly Leavens. Val Govig takes the reins – the first issue of Kite Lines featuring Paul Garber in 1977.

Shelly Leavens. The AKA newsletter officially became Kiting in 1985.

With Vol. 1, No. 2, Kite Tales now officially had a name, and so did the new association, with a logo on the way. “After asking for suggestions, and getting them, the matter of naming our new kiteflier’s organization got very confused and we arbitrarily went ahead and named it ourselves. We hope we didn’t get anyone mad,” wrote Ingraham to a group that had now grown to a whopping 23 members, including one woman.

Along with Rogallo, they could now add Domina Jalbert and Paul Garber to their list of members, which was looking more like a famous inventors club. [Editor’s Note: Rogallo and Jalbert were soft-kite pioneers. Rogallo invented the Flexikite and is known as the father of modern hang-gliding. Jalbert’s parafoil designs became the standard of parachute design.] “Best of success in your venture which should be very interesting to watch and who will be in it [sic],” Jalbert wrote in a letter enclosing ten dollars (membership was only five dollars at the time). Not only were famous inventors card-carrying members, the AKA was getting some national notoriety through the Associated Press, and as Ingraham proudly noted, a mention by news commentator Paul Harvey. Within one year, this “silly little club” had hit the big time.

ten·seg·ri·ty (těn’sěg’rĭ’tē) n.

1. The property of structures that employ continuous tension members and discontinuous compression members in such a way that each member operates with the maximum efficiency and economy.

One may easily predict the next chapter.

Over the next twelve years, the association’s membership grew exponentially, with each member glued to the pages of Kite Tales. It was a conduit, a sounding board, and the way to find out what was going on in the world of kites. Recall in distant memory a time before the internet, email, and web forums, that there was such a thing as an affordable and expedient postal system and that people took time to type letters to each other. The stacks of clippings, kite plans, and correspondence in the AKA archive are a testament to the imperative of communication between kitefliers, a desire that was in part satiated by a now- overwhelmed editor of Kite Tales.

It is in spring of 1977 that we first see a change of the guard. Ingraham has sold Kite Tales and thus handed the line to Valerie Govig, who then publishes Kite Lines. This is the beginning of numerous transitions for the AKA, and as noted in his farewell statement in the issue, “few have the rather unusual and highly important requisites of editing and journalistic training which Valerie possesses in addition to a love for kiting and all it entails.” However, it is with a melancholy tone that Ingraham continues, quoted here at length.

The relinquishing of this cherished task, despite all its magnifying complications and seemingly insurmountable problems, it not without pain and diminishing of our pride in accomplishment. For 12 years we have been in touch with practically the entire world. We have made literally hundreds of personal friendships and reached out from our remote headquarters into virtually all corners of the globe. The membership of the AKA, despite the common concept of kiting as kid’s stuff, is of the highest cultural and intellectual level. We have contributed in a small but relatively important way to the socio-economic factor of the world and take pride in the fact that our efforts have made a valued impact upon modern society.

Shelly Leavens. An early bumper sticker encourages membership, and a signed cloth commemorates attendees of the first AKA Convention at Ocean City, MD in 1979.

Drachen Foundation. AKA Founder Bob Ingraham with his wife, Hazel.

Ben Ruhe. Bob and Jewell Price at the AKA Convention in Tulsa, OK in 1995.

Shelly Leavens. The AKA archives housed at the World Kite Museum, Long Beach, WA.

Ingraham had set the bar high and over the next several years the AKA did indeed formalize further, as he had hoped, but also seemed to struggle with its identity on numerous levels. As Kite Lines, the “Quarterly Journal of the American Kitefliers Association,” was still finding its footing as a business venture, a new body of members was also forming a non-profit Board of Directors and organizing the “First Annual Meeting” at Ocean City, Maryland, held September of 1978. As noted in the first “new” AKA newsletter, Letter from the President, “the meeting was a grand success,” and it seemed to usher in a new era for the AKA as an association. Successful and inclusive as it may have been, the roles of the two entities, Kite Lines and the “new” AKA, were difficult to define, which eventually led to frustration and miscommunication.

In years to follow, with the existence of both a non-profit AKA newsletter (renamed Kiting in 1985) and the for-profit Kite Lines, there was some tension regarding advertising and content. In numerous letters from Govig, she expresses that the AKA was duplicating, rather than merely complementing, her efforts in Kite Lines. The AKA newsletter was no longer merely “A Letter from the President,” but had become a full-on entity of feature stories, ads, and member- contributed information, much in the vein of Ingraham’s Kite Tales. Govig writes to Milly Mullarky and the AKA in 1982, “This is the basic problem we have with the AKA. We would like the two different organizations to exist in comfortable parallel…overlapping only when jointly planned projects make it useful to share costs and resources. AKA needs a clear image of itself. In this, I think we could help you.”

Despite some continued friction and not without their own individual hurdles, both Kite Lines and the AKA grew independently and flourished simultaneously for many years. Kite Lines was glossier than ever, and in 1991, Brooks Leffler was hired as the first AKA Executive Director with a membership approaching 3,000. Ingraham, who passed all too soon in 1995, stayed involved into his later years, in particular helping to write and publish the Kiteflier’s Manual in 1990, and as he’d hoped, “get around a bit and fly kites with people I’ve known a long time.” Fast forwarding, kite fliers also saw the passage of Kite Lines in December 2000, leaving Kiting as the last remaining kite publication of its type. In a rapidly accelerated world where print media is being questioned more than ever, what of the AKA a decade into the new millennium?

as·so·ci·a·tion (ә-sō’sē-ā’shәn) n.

1. An organization of people with a common purpose and having a formal structure; friendship, fellowship, companionship, alliance, union. 2. The connection or relation of ideas, feelings; correlation of elements of perception, reasoning, or the like.

Community interaction is at the heart of why people join associations. They want to work with other like-minded people on a common cause or interest – be it the cure for a disease or the pursuit of a hobby like kiting. While the complexity of the AKA and its role to kiting has evolved since the days of Ingraham’s Kite Tales, the current association still has the purpose of bringing people together to have a collective, positive impact on members’ lives and society.

Benevolence notwithstanding, running an association with yearly turnover in its Executive Committee, and in tough economic times, is not easy or inexpensive.

Ali Fujino. Strolling the boardwalk and admiring the kites at the 2004 AKA Convention at Seaside, Oregon.

Ali Fujino. Kites at the 2008 Convention. The Convention will again take place at Seaside this year.

AKA President Barbara Meyer wrote in a web forum post, dated May 17, 2010, “Our financial situation continues to be a challenge. The auction last year was $10,000 less than the previous year. Your board has been working hard to cut expenses, and raise income… Your membership, and donations will help keep that loss to a minimum.”

The AKA exists for its members and encourages membership at any chance it has. However, the AKA also wants membership to its association to feel exclusive, a password protected “Member’s Only Club House” on the website and a glossy issue of Kiting in the mailbox are two examples, because this is one of the only ways the AKA can bring in the money it needs to stay aloft. This exclusivity is also what makes kiting as a sport, art, science, and ritual pursuit challenging to enter into as a newcomer, and challenging to transition people to beyond their experiences as a child. At a recent kite festival, Meyer’s 19-year-old daughter was the only teenager. Meyer feels this demographic is hard to reach, and specifically noted that she would like to engage more people ages 15-30.

John Baressi, editor of the online Kitelife Magazine, wrote a critique of the AKA on the matter in “Kites…Life: Are we doing everything we can to reach out the public?” in the May/June 2010 issue.

At a time when “kite proponents” speak of a desire to increase our ranks (fliers, club members, competitors, whatever), I’m not sure that a “big picture” approach is being properly applied in many cases, or even realized… Of course, it warrants mention that the AKA isn’t some headless corporation or government, although it’s often portrayed that way… The AKA is a body of kitefliers, just like you and I, a broad sampling of our community, albeit just those folks who were willing to actually step up and take the heat that comes with trying to handle an organization… Point is, whatever you see “the AKA doing” is in fact what we’re doing to some extent, as the board is by majority a panel of folks that we’ve voted for, or not voted at all, which just might be worse.

It’s clear that it takes participation from members for the AKA to be strong and grow, and despite the inherent nature of kites as objects of doing, the AKA still has the challenge of staying relevant. Some may cringe at the term, but social media is being looked at as one avenue to attract a new, younger audience to kiting.

Business author Brian Solis began his definition of social media with the question, “How do we ensure that conversations don’t leave us behind?” His answer, “We engage and continually participate.” He continues, “there has been a fundamental shift in our culture and it has created a new landscape of influencers and an entirely new ecosystem for supporting the socialization of information – thus facilitating new conversations that can start locally, but have a global impact (italics mine).” Even though Solis is referring to social media, his words brought me right back to Ingraham’s first issue of Kite Tales, developed out of the small town of Silver City, New Mexico. It did start locally. It did have global impact. What Ingraham did may not be on the level of the millions using social media, but it was appropriate for his time and was essentially the same thing – the beginning of a vast network. It’s now up to the AKA to make the shift.

Mel Hickman is the current AKA Executive Director and he spoke at length about his efforts and excitement for what is to come, and to the balance the AKA is seeking. On the virtual side of things, there is a new webmaster currently re-designing the AKA website and the AKA is actively using Facebook. “I think it has incredible potential to be a tool,” commented Hickman, “but a URL can’t match flying a kite in the sunset or flying a kite as a family.” Hickman feels that while the AKA can utilize social media as a way to reach people, it is the work of sanctioning events, hosting a major convention, and generally encouraging people to build and fly kites that truly promote the association’s goal of providing opportunities for people in real life.

In a recent interview I asked Meyer how she felt about upholding the larger-than-life legacy of Bob Ingraham via the AKA. She commented that she felt the active committee structure was a way the AKA could continue to preserve continuity and also uphold Ingraham’s tradition of the organization being by and about members. It seems that Meyer’s “loud and clear” message of late is not much different from Ingraham’s in 1964. “WE NEED MEMBERS,” he wrote in bold capitalized typeface. “THE MORE MEMBERS WE HAVE THE BETTER ORGANIZATION WE HAVE.”

“I am so proud to be associated with the AKA. It truly does unite kiters around the world in the goal of sharing our mutual love and passion for kites,” wrote Meyer in her June 23rd email message to AKA members. Besides a monthly email from the President, membership is shown on the AKA website to include a litany of other benefits, including discounts, insurance, and without fail, Kiting. But at the end of this long list (and at the end of the day) there is something that is at the heart of the AKA, at the heart of what Bob Ingraham set out to do. Perhaps it is the best benefit of them all: friends in the field.

Join Drachen Foundation at the upcoming American Kitefliers Association Convention October 12-16, 2010 in Seaside, Oregon! More information online at: http://www.aka.kite.org/

REFERENCES

Baressi, John. “Kites…life: Are we doing everything we can to reach out the public?”Kitelife Magazine. Issue 72, May/June 2010. Online access: http://kitelife.com/magazine/issue72/life72/content.php

Braswell, Welca D. “Red”. “Greetings from the President of the AKA!” Letter from the President. Vol. 1, No. 1 January 1979.

Hickman, Mel. Telephone interview with the author. June 24, 2010.

Ingraham, Bob. Kite Tales. Vol.1, No.1 1964 through Vol 2. No. 1 1965.

___ Kite Lines. “Flying with The Old Pro.” Vol. 1, No. 1. Spring 1977.

Leffler, Brooks. “Digging in AKA’s Basement.” Kiting Vol. 14, No. 2, March 1992.

Meyer, Barbara. Telephone interview with the author. June 8, 2010.

___ Web forum post. “May news.” May 17, 2010.

___ Email message. “Almost July news from the AKA.” June 23, 2010.

WEBSITES

http://dictionary.reference.com

http://www.asaecenter.org/AboutUs/content.cfm?ItemNumber=16309

http://www.webpronews.com/blogtalk/2007/06/29/the-definition-of-social-media

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1696&dat=19690130&id=adIdAAAAIBAJ&sjid=eUYE AAAAIBAJ&pg=5662,3965760