Dörte and Frank Schulz

From Discourse 6

Viborg Archive. A photograph of the station from the local historic archive in Viborg, Denmark.

As everywhere worldwide, so too in Scandinavia were the upper air strata being researched at the beginning of the twentieth century with the aid of kites. The goal of this research was to explore the more exact nature of these strata and to obtain knowledge of weather and climate.

At a meeting of the Meteorological Society in Berlin in 1901, it was decided to found a meteorological station for the research on the upper air strata upon the suggestion of Frenchman Teisserenc de Bort. The placement of the station was so chosen that the sea, with its specific weather conditions, would not be far away, and also so that observations could be made independent of ships.

The small village of Hald, near Viborg, in Denmark was selected as the location. The intent was to make as many valid meteorological measurements as long lasting as possible, with the help of kites and balloons.

This plan was successfully inaugurated by 1902 with the help of many contributions. The construction of the station was begun in the spring of 1902, and as early as July 1902 it was in business. The considerable money needed for the realization of the station came from, among others, Teisserenc de Bort, who gave 50,000 francs from his private fortune; from the Danish state participating with 14,000 francs; diverse bequests from Denmark at about 24,000 francs; and from Sweden, providing 28,000 francs. The land upon which the station was to be erected was also a gift, provided without cost by local chief hunting ranger Krabbe.

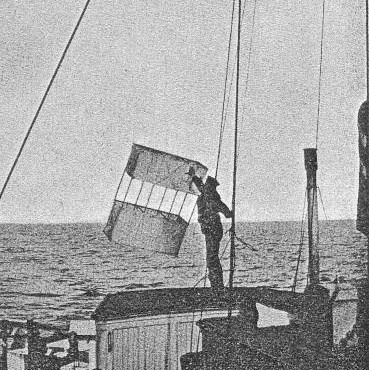

Teisserenc de Bort. The war ship “Falster,” from which several flights were taken.

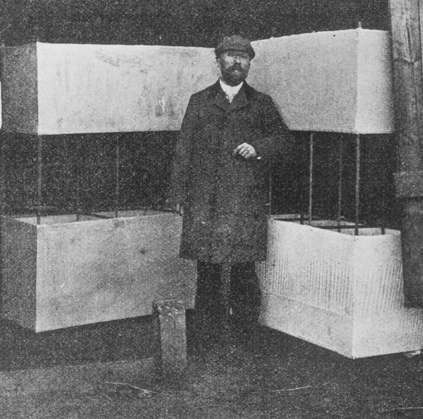

Teisserenc de Bort. Station captain de Bort.

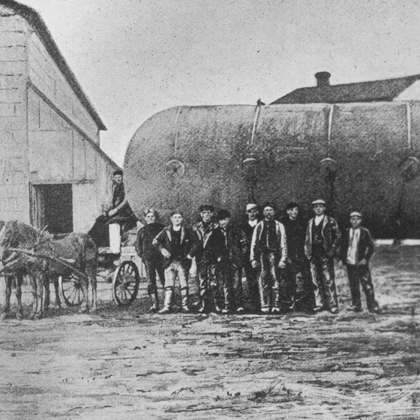

Teisserenc de Bort. A gas balloon.

Photographs from the report “Traveaux de la Station Franco-Scandinave de sondages Aeriens a Hald 1902-1903” by Teisserenc de Bort.

Teisserenc de Bort became the director of the station. Also assuming leadership roles were H. Hildebrandsson of Sweden and Adam Paulsen of Denmark, who was appointed by the Danish Meteorological Institute. Altogether the station employed about thirty workers. Among them were carpenters for kite construction, meteorologists, and mechanics.

There were seven buildings on the station. There was a rotatable observation and winding tower, a balloon hangar, a kite workshop, an office building, a machine workshop, a laboratory, as well as, of course, the house for Director Teisserenc de Bort. The station also had a gas container and an automatically driven kite winder.

A total of 311 flights with kites and balloons were carried out from July 10, 1902 to May 13, 1903. For the kite flights, Hargrave or modified Marvin kites, from 3.3 to 8.2 square meters in size, were used. The aim was the longest possible flight with correspondingly long diagrams or sketches. The longest of these flights was an uninterrupted 26 ½ hours. The average altitude for flight was 2500 meters. The highest flight, 5900 meters, was a record at the time. On account of the frequent very long and high flights, the material loss was correspondingly high.

In order to keep the cost of lost or damaged kites as low as possible, the station administration offered a reward for the return of torn kites and lost instruments. For the return of a kite, a reward was promised of between 5 and 10 Danish kronen.

As a complement to the balloon and kite flights from the station, flights were undertaken from war ships. A total of 15 flights from the “Falster” and the “Loeveroem” took place.

There were surprises – positive as well as negative – for the workers at the station. As early as November 1902, shortly after the beginning of operations at the station, the strongest ever registered storm swept over Jutland. On account of this storm, several of the station’s houses were partially or heavily damaged.

Also in November 1902, Vladimir Koeppen and Richard Assmann visited the station in Hald. With this opportunity, Richard Assmann presented his friend Teisserenc de Bort with the Red Eagle Order Second Class, in the name of Kaiser Wilhelm II, for his work in meteorology.

Altogether 311 kite flights were made in just the first year of the station. Fifteen more were made from ships. Of course, a number of balloon flights were also made from Hald.

The gas needed for the balloons was brought by horse-drawn cart from Viborg. Often young boys repeated a typical prank: after the cart driver, Fritz Langvad, had filled the balloon, these kids from the town poked a hole in the covering with a needle. This resulted in a slow loss of gas during the trip to the kite site. After Fritz Langvad had arrived at the station, the loss of gas was so great that he had to go back once more to get new gas.

When the station was closed as planned in the summer of 1903, all buildings were auctioned off and dismantled. A few of the buildings, including the former residence of Teisserenc de Bort, were reconstructed and are standing in the village of Dollerup, a few kilometers from their original location. There they serve to this day as homes, completely renovated and converted.

Frank Schulz. A few of the buildings from the meteorological station, including the former residence of Teisserenc de Bort (pictured here), are standing today in the village of Dollerup, a few kilometers from their original location.

Frank Schulz. A few of the buildings from the meteorological station, including the former residence of Teisserenc de Bort, are standing today in the village of Dollerup, a few kilometers from their original location.

The owners of the houses today interestingly know nothing of their history. Only after we had shown them some newspaper clippings during our visit were they enlightened.

In addition, a stone monument was not finished until 1938, after a number of complications, through the efforts of the director of the office of tourism. The stone exists today and stands on the Heide near the town of Viborg. On the upper plate of the monument is the name of the station, and on each of three stone posts is the name of one of the three directors: Teisserenc de Bort, Adam Paulsen, and H. Hildebrandsson.

A paper on the work of the Franco- Scandinavian station at Hald was published under the title “Traveaux de la Station Franco-Scandinave de Sondages Aeriens” (”The Work of the Franco- Scandinavian Station in Air Observations”) by Teisserenc de Bort. Reports from H. Hildebrandsson and A. Paulsen are also contained in the paper.

Translated by Robert Porter