Jane D. Marsching

From Discourse 4

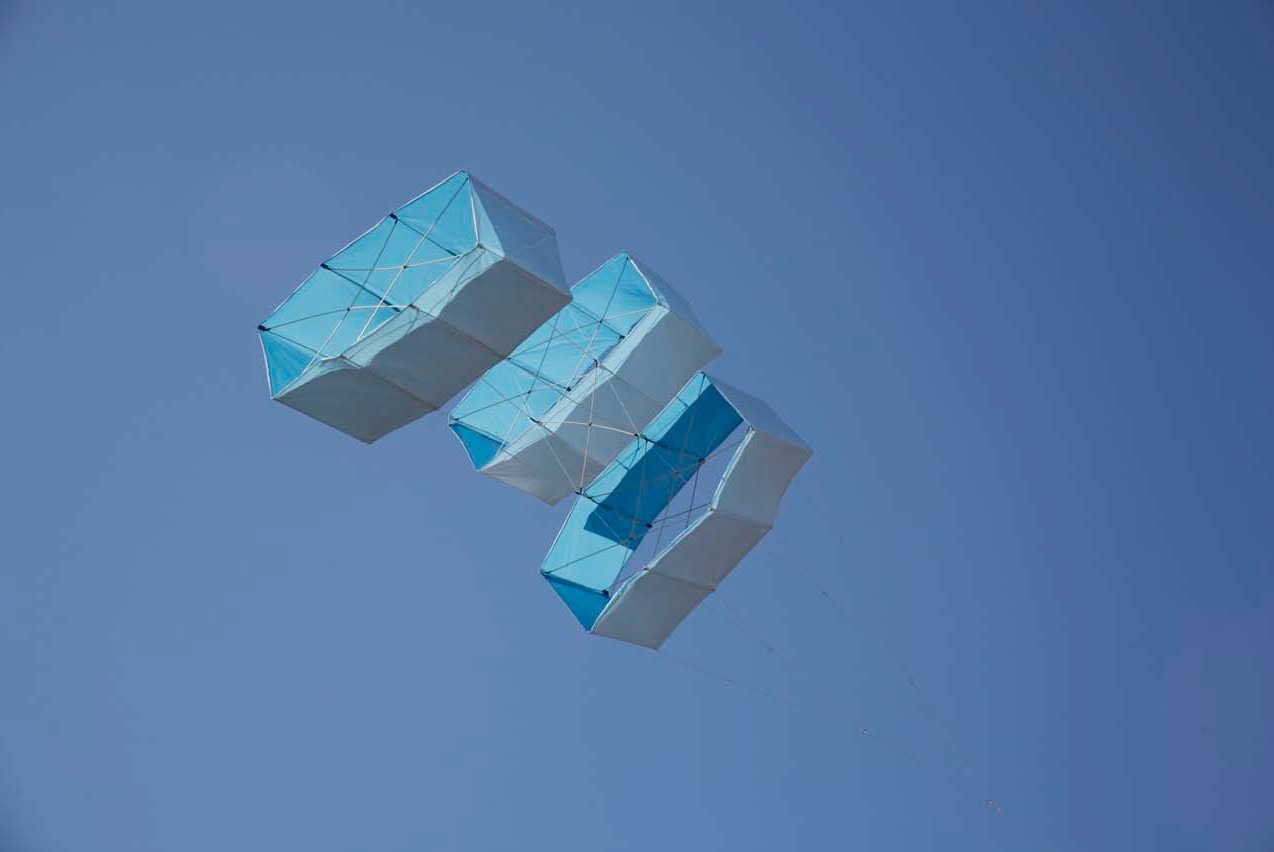

Jane D. Marsching. Test Site: Hargrave triple cell box kite failed experiment from the 1890s remade in 2008 flying over Blue Hill Observatory, March 2008.

“The eye sees what it has been given to see by concrete circumstances, and the imagination reproduces what, by some related gift, it is able to make live.”

– Flannery O’Connor

Blue Hill Observatory in Milton, MA, first built in 1885, is home to the oldest continuous weather record in the United States. A hill

635.05 feet above sea level, Blue Hill Observatory is also the site of some of the earliest and most significant kite meteorology experiments in the United States. In the 1890s balloons and kites began to be used by the US Weather Bureau to gather climate data from the upper atmosphere. Alexander McAdie started kite experiments at Blue Hill in 1885 for the purpose of studying static electricity in the sky. In 1893 Australian inventor Lawrence Hargrave successfully flew his first cellular or box kite. Hargrave, who had in his early life been an explorer, cartographer, astronomical observer, and inventor of shoes that walk on water, [1] became in his thirties an investigator of all things aeronautical. He believed passionately (unlike the Wright Brothers who were patent crazy) in the importance of research being open for the benefit of all and was passionately anti-patent: “The life of a patentee, he wrote, was spent ‘in a ceaseless war with infringers’. Any ‘loot’ was merely ‘squandered’ – ‘broadcast among shoals of sharks’. More importantly, patents served to ‘block progress’ by taxing future development.” [2] His many papers included detailed sketches and information to help other early aeronautical inventors to solve the perplexing problems of human powered flight. On the 12th of November, 1894, he flew four linked box kites that lifted him sixteen feet into the air. His sturdy box kite was adopted by Blue Hill Observatory and the US Weather Bureau as the standard design for their weather kites and continued to be used for many years. The history of kites for research continued at Blue Hill Observatory through the 1920s. With the advent of soundings taken from airplanes, the last kite station was closed in 1933. [3] A new history of kites for low altitude wind appreciation, educational purposes, kite aerial photography for vegetation research, aesthetic pleasure, and more has begun in the 21st century with the Blue Hill Observatory Science Center.

My ongoing project, Arctic Listening Post, has explored our past, present, and imagined future human impact on climate change. I’ve created images based on data from digital elevation models of glaciers, videos from webcam images from the NOAA’s north pole webcam, and animations of data from weather buoys in the northern seas. The work seeks to make visible the story of data. The scientific community is awash with studies of the effects of climate change from paleoclimatology, to glaciology, to oceanography, and so much more. All these studies get filtered through policy reports, scientific journals, and the mass media, but they end up on our plates as dry reports, difficult to consume and near impossible to see with any clarity. By taking this data, its histories, current crises, and future probabilities, I hope to reinstate its narrative, give a fuller picture of the impact of data on our lives, and create a sense of wonder and urgency.

I became an artist in residence at Blue Hill Observatory in the winter of 2008. Inspired by the amazing history and ongoing work of the dedicated observers and staff, each day I would drive up the road to the old building past the usual roadside trees into a more alpine landscape littered with scrub pines, choke cherry, cedar juniper, and grey birch. The view of the surrounding eastern Massachusetts landscape stretches for miles. On low haze days (see Blue Hill’s “Haze Cam” at http://www.hazecam.net/bluehill.html, which tracks the effects of air pollution on visibility) observers note in their daily discussion that they can see for more than 65 miles.

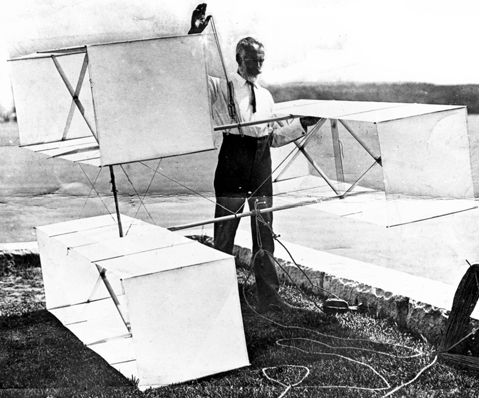

SSPL / Science Museum. Lawrence Hargrave with his triple-box kite arrangement, 1898.

The rich history of the Observatory became the jumping off point for my work there. The ongoing activities at the observatory – air pollution monitoring, constant surface observations of all weather characteristics, careful archiving of data, and daily weather bulletins – all provided me with rich resources for interweaving a consideration of our human effect on the climate with the history and landscape of the Observatory. In collaboration with the Blue Hill Program Director, Don McCasland, who has a rich and skilled history with kite building and flying, I built a kite that is a model of a failed experiment of Hargrave’s in the years that he was testing various kinds of box kites. The version I chose was a triple cell kite, which has close visual associations with the Wright Brothers early glider flights, as well as more ordinary modern day gliders. The kite we made in silver and blue is a salute to the innovation and sense of wonder that Hargrave possessed.

Jane D. Marsching. Don flying Test Site: Hargrave triple cell box kite failed experiment from the 1890s remade in 2008.

Jane D. Marsching. Test Site: Hargrave triple cell box kite failed experiment from the 1890s remade in 2008.

Lewis Hyde’s book The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property travels the worlds of anthropology, literature, poetry, art, economics, philosophy, and psychology to discover the ways in which art can be a gift to the maker, the audience, the world. The point that inspired my work in the project Test Site is this:

A work of art breeds in the imagination of the viewer. In this way the imagination creates the future… The imagination can create the future only if its products are brought over into the real… Without the imagination we can do no more than spin the future out of the logic of the present…[4]

If, as the November 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s report states, we have moved from a state of prevention to the need for adaptation to the new world wrought by anthropogenic warming, then how can we stay with the long (thousands of years) effort – both great and tiny, both eons and moments – in the making that is required? We have had a feeling that climate change can be stopped; our nascent partial understanding of it as a change in temperature or precipitation needs to become an interdisciplinary collaborative global wisdom about its pervasive effect on all aspects of our planet, population, and culture. But we are tired of it already. We’ve changed our lightbulbs, we’ve cut back on water bottles – enough already! The facts are too complex to encompass, the situation too dire to contemplate. Lewis Hyde’s thoughts on art as a transformative vision of the future are central to the kinds of efforts we can make to bring a sustaining sense of wonder, hope, and possibility to our future in the face of climate change.

The Hargrave triple cell box kite failed experiment from the 1890s remade in 2008 is a gift for the site, observers, staff, and climate of Blue Hill Observatory. Can one have a relationship with a site just like one has with people? Can one consider the climate a living being? Can we afford not to? On the spring equinox of 2008 I read a story to the site on a cloudy afternoon. I read the central chapter of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth. What gift can one give the sky that from its vantage point sees everything? Perhaps a story of the things that it can never see. In the passages I read to the sky, the main characters, Lidenbrock and Axel, come at last after their long travails to the absolute center of the earth:

At first I could hardly see anything. My eyes, unaccustomed to the light, quickly closed. When I was able to reopen them, I stood more stupefied even than surprised.

“The sea!” I cried.…

I gazed upon these wonders in silence. Words failed me to express my feelings. I felt as if I was in some distant planet Uranus or Neptune – and in the presence of phenomena of which my terrestrial experience gave me no cognisance. For such novel sensations, new words were wanted; and my imagination failed to supply them. I gazed, I thought, I admired, with a stupefaction mingled with a certain amount of fear.

Jane D. Marsching. Jane D. Marsching reads Jules Verne’s A Journey to the Center of the Earth to the sky at Blue Hill Observatory on the spring equinox 2008.

This moment of discovery of something entirely unknown and magical was my gift to the site, a story of the center of the earth, something which the sky cannot see.

In early April Don McCasland, John Nevins, and I attached sound equipment to the kite line and launched at sunset the Hargrave triple cell box kite failed experiment from the 1890s remade in 2008. With filmmaker Noah Stout, I videotaped the kite’s flight through the sky above the observatory, capturing the flight of a flock of geese, the hovering of the kite over stands of pines, and the buffeting of the cells in the varying winds. The sound equipment broadcasted through a small microphone attached to an MP3 player a recording of my reading of the Verne story to the sky. Now, the upper atmosphere could hear a science fiction imagining of the center of the earth. In the final video that documents this flight, the sound is a recording of the sky hearing the story read to it, filled with sounds of the wind, of the flapping of the kite nylon, and the singing of the string in the gusts.

Another similar kite project was part of a live kite flight performance at the Observatory on May Day 2008. Don McCasland and I designed another kite with colors of the hilltop and sky, which carried sound equipment that broadcasted to the audience below on the ground a sound recording by author and artist Mark Alice Durant. This wry poetic spoken word performance interwove facts about kiting with personal narratives:

Some tips on untethered flight:

Upon launching any object towards the heavens be aware of the limits of your imagination and provide the corresponding length of string

To avoid boredom a kite desires steadiness with occasional minor variations – launch your kite in a subtly modulating current

Tether your thoughts to earthly concerns

Remember that clouds obscure the sun Remember that the stars continue to shine in the daylight hours

Never use wire for a kite string Never fly a kite during a full moon or anytime in November—unless you live in the southern hemisphere in which case you should avoid April

Never fly your kite in the rain

Don’t fly your kite near electrical wires Avoid trees-they eat kites

Do not fly near airports

While running to launch your kite avoid holes in the ground, gullies or slopes, as well as broken glass or any other debris on the field

Do not fasten yourself to your flying line

Avoid flying your kite in city streets Do not climb high trees or rooftops to rescue your kite

Do not read The Kite Runner Do not watch any Fellini films

Wind is your friend up to a point Excuse me while I kiss the sky

Don’s graceful kite took some time to get up in the air; the winds took their time picking up enough. Finally a wind came in from the east, and the kite flew up and delivered Mark’s text to the sky.

- http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/database/?irn=128851&collection=Lawrence+Hargrave

- L Hargrave to Illustrirte Aeronautische Mittheilungen, 28 June 1903, Hargrave papers: folder no 113, vol 4. Quoted by Tim Sherratt, ‘Remembering Lawrence Hargrave’, in Graeme Davison and Kimberley Webber (editors), Yesterday’s Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and its precursors, 1880-2005, Powerhouse Museum in association with UNSW Press, Sydney 2005, pp. 174-185.

- http://www.islandnet.com/~see/weather/almanac/arc2006/alm06apr2.htm

- Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property. New York: Vintage Books, 1979, p. 193-194.